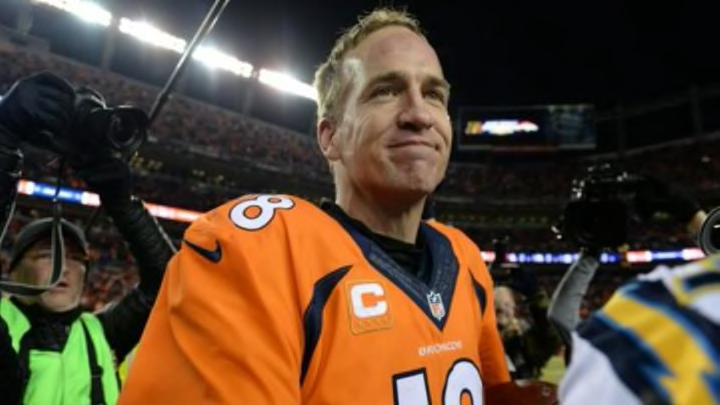

Peyton Manning’s alleged HGH use shouldn’t matter

By Stu White

As of today, it’s still unknown as to whether or not Peyton Manning used any of the human growth hormone (HGH) allegedly sent to his wife in 2011. Since the allegations first surfaced last late last month, thanks to an investigative report by Al Jazeera, Manning has aggressively denied any wrongdoing, hopping on ESPN to defend himself and enlisting the PR help of Ari Fleischer. Questions have been raised regarding the credibility of Charles Sly, one of the main sources cited in the Al Jazeera report, who has walked back on his initial accusations, perhaps in an effort to protect himself and his business partner Jason Riley of Elementz Nutrition. Fans have been reminded of the overall inadequacy of the NFL’s HGH-testing procedures, as well as the fact that performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) have been part of pro football for decades. Contrary to the assertions of Jim Nantz, the Manning-HGH rumors constitute an important story, one that will continue to play out for months.

What’s been interesting to note, however, is that while a lot of digital ink has been spilled about Manning and HGH, the overall tenor of the responses has been on the side of indifference, if not acceptance. Sure, Manning, an aging player with a damaged neck, may have used HGH a few years ago. So what? In other breaking news, water is wet. This marks a shift from how the sports populace, both media and not, previously thought of PEDs. In the not-too-distant past, the use of chemical enhancements to promote physical recovery was seen as a sin, an affront to the holiness of capital-s Sportsmanship.

Why the change? Well, frankly, because an athlete such as Manning potentially having used PEDs is not that big of a deal, at least not to fans who value the health of players over the necessity of following arbitrary rules.

Priorities have shifted, sparked by a greater understanding of football’s dangers. Appeals to the sanctity and the purity of the game aren’t as persuasive in the modern football era, a time when only the willfully naive remain unaware of the long-term physical damage intrinsic to the sport. There’s no way to watch football in 2016 and not cringe at every woozy, stumbling player who requires assistance to simply walk to the sideline: too much is known about concussions, about how tiny ones accrue over the course of a game, a season, a career. Bodies in pain are no longer fodder for cackling ESPN “Jacked Up” segments. The illusion of superhuman physical prowess previously attributed to football players has been erased, replaced by a more complete understanding of football players as actual people, their enviable salaries and seemingly impossible bodies not adequate shields against the realities of chronic pain and suffering. This new understanding makes cries about fairness and “playing the game the right way” seem quaint, if not ugly and somewhat callous. Why elevate something as arbitrary as a game over the actual people who participate in it?

This is why so many have refused to call for Manning’s head, despite contemporary society’s tendency — fueled by social media and the cutthroat game that is the online writing economy — to blow every little situation out of proportion: it’s not that people don’t at all care that a player — one of the most famous in the league, a guaranteed Hall of Fame inductee when his time comes — allegedly used performance enhancing drugs, but rather people care more about that player’s physical health than his potential adherence to a rulebook. Rules and regulations matter, yes, but not more than a human’s well-being. If Manning indeed used HGH to repair his damaged body, and if that alleged HGH use granted fans the lucky privilege of seeing one of the all-time greats take the field for a few more years, it’s hard to make the moral argument against that, against a person healing himself in order to sustain the life and job he loves.

Whatever the fallout from the Manning situation ends up being — and it appears no final verdict will be administered anytime soon — it’s hard not to see it as a moment representative of a turning tide, a reframing of how fans think about the physical realities of one of the most violent forms of entertainment on the planet. HGH use shouldn’t be outright encouraged, not at least until more scientific research has been conducted regarding potential long-term harm, but it also shouldn’t be — and is seemingly less and less, at least generally across the sports media spectrum — demonized. This seems the healthier attitude to take, for it prioritizes the tangible (a body in need of healing) over the abstract (the sanctity of a record book or a stat sheet). If the expectation is that people should risk the vitality of their bodies for a large paycheck, then it’s reasonable to support whatever methods sustain those bodies, even if those methods go against tradition, against invocations of sportsmanship and propriety passed down from generations that didn’t know any better, that didn’t have access to the knowledge about football’s destructive nature readily available today, impossible to miss. This new attitude is not a surrender or an acquiescence: it’s an acceptance of reality, a reasonable and rational reaction to the truths of a game defined by violence. It’s a compassionate, humane response.

A rule being broken shouldn’t be seen as less palatable than a body suffering the same fate. To think that way, which is the way of traditionalists, of the unfeeling old guard who see advancements in compassion as harbingers of the apocalypse, is to strip the humanity out of an undeniable human activity. Society already goes to great lengths to dehumanize, to reduce, to replace flesh and blood with bylaws. If Manning flouted proper sportsmanship in an effort to regain his health, if he used a banned chemical in an effort to continue finding personal fulfillment in one of the things he presumably loves most in the world — a thing that also happens to be frighteningly dangerous, where catastrophe lurks on every play — then all the power to him. The rules of a game are replaceable, amendable, ephemeral, abstract. A body isn’t.