We don’t have to like each other

By David Ramil

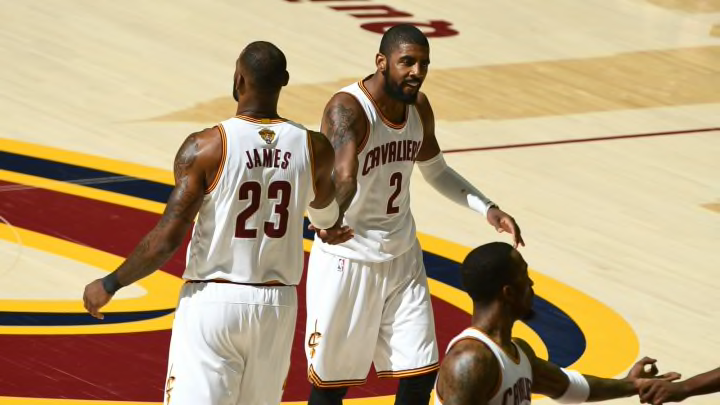

It was a matchup of some significance, as much as can be attributed to any one game in a long regular season. Still, it was a battle of title contenders, rife with talent and the requisite levels of drama. As such, it didn’t disappoint. It was a tightly-contested game decided by a tightly-contested shot within the last few seconds of play. The player who made it was embraced on the court by a superstar teammate, all smiles, warmth and jubilation.

The two players were Kyrie Irving and LeBron James and the game, which took place on Christmas Day, was just over nine months ago.

The display seems impossible and almost alien given what has happened in the relatively short time since. Irving requested a trade from Cleveland, was subsequently sent to Boston, and the fallout of that transaction has shed a light on the nature of the relationship between these former teammates. Suspending the idea that Irving should spend his entire professional career pursuing championships (and that partnering with James is one of the surest way to achieve that goal), the trade has also led to questions about the depth of this association. The appearance, for those inclined to look for those things, was that the two shared a friendship and mutual respect. The reality seems to prove otherwise.

Read More: The NBA’s super team era has placed championships over individual awards

And yet the larger question, one that remains mostly ignored among the narratives unraveling out of this public separation, is why we choose to impose our notions of friendship on people who only share a profession in common. Athletes have long been viewed as idealized members of humanity but much of that ascription has been based on physical precedents. But while many fans find it a painful chore to join their coworkers for 2-for-1 margaritas at the nearest Chili’s, they expect NBA players to forge unbreakable friendships off the court while maintaining a stable chemistry on it.

The two aspects — friendship and chemistry — are easily confused and can blend particularly well in the NBA. The language of the league can come across as canned and cliched but it’s one players have long been ingrained to speak. Terms associated with the individual (“I”, “me”, “mine”, etc.) have long been interpreted as selfish except when assuming blame (“I missed the shot”). Success is shared, and so “we” win as a team in spite of the accomplishments of any sole player.

There are certainly moments of camaraderie, often punctuated in physical, and therefore obvious, ways: an embrace, a high-five, and perhaps even a well-intentioned pat. These are usually reserved for people that share a connection more deep than a collegial one but are commonplace during any game.

The locker room is no less or more diverse than any number of workplaces, yet that individuality is routinely ignored. Players of different races, political leanings, faiths and backgrounds are collectively lumped, further promoting the impression of friendship.

There is also an undeniable intimacy that forms between NBA employees. Teams travel across the globe and share hotel accommodations on the road. There are practice sessions, morning and late-night shootarounds, functions and charity events, as well as the games themselves. All in all, countless hours are spent together, during which you see teammates at their barest and most basic levels. Rare is the group of accountants that crunch numbers and file returns before hitting the showers together, only to return to the office the next day and do it all over again.

“That’s why it’s chemistry. You can’t predict it or plan for it. You just have to hope that it develops.”

Factors like shared experiences and physical contact might play a part in traditional friendships but that is hardly the case in the NBA. There are well-documented exceptions that should be lauded, not as evidence of the norm but rather because of how unlikely they actually are. Players are constantly competing with one another, whether for playing time or to win a positional battle, for status or money. The inherent physicality of the league make friendships seem impossible, even going beyond the flimsy connection of merely working the same job. The challenge is one shared by most coworkers, even without having to throw elbows for the corner office or be separated by teammates while fighting over the use of a stapler.

James himself, who has played with dozens of different players throughout his 14-year career, spoke in 2015 of only having “three very good friends in the league” with everyone else falling into the category of “a bunch of teammates.” But even after explaining his views, the need to view James’ colleagues as friends takes a turn toward the pathological. The context of the story, one presumably written free of irony, was the burgeoning relationship between James and Irving that was even described in the piece as “friends away from basketball.”

If friendships are rarely formed, there is still the long-standing perception that successful teams are linked by a tenuous chemistry at the very least. However, as far back as 1991, Sport Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite looked at the role of chemistry and debunked its impact, even noting that the Oakland A’s of the 1970s “won three straight World Series while fighting among themselves like inmates at a reform school.” And while the two terms of friendship and chemistry have been used interchangeably for decades, a new definition of the latter might be in order.

“I just like thinking that they get along, that these guys are friends.”

Jeff Weltman has spent his whole life around basketball. His parents worked for the NBA and ABA, while Weltman himself has spent time with six different teams, rising from the position of video coordinator with the Los Angeles Clippers to his current one as the Orlando Magic President of Basketball Operations. He’s assembled teams, all with varying levels of success, but acknowledges that there might not be a clear pattern that guarantees on-court camaraderie.

“Building a team of veterans and young players…it all sounds good, right?” said Weltman during the Magic’s media day in late September. “The fit and the chemistry that evolves out of that [combination] is unpredictable. That’s why it’s chemistry. You can’t predict it or plan for it. You just have to hope that it develops.”

Weltman does admit that when it comes to his team-building approach, there at least has to be a shared psychological characteristic, even if it isn’t an exact science “The way that you try put [chemistry] into a place to develop is to bring in high-character guys that have the same goal. That’s what we’ve tried to do and I hope that it comes to bear.”

Using that as a reasonable premise for what might be interpreted as on-the-court connectivity, what is really transpiring is players sharing the goal of winning while sublimating their own personal feelings about each other, ones that may — but most likely won’t — include friendship.

Even a 2010 study that shows that when teammates make more physical contact they win more is likely confusing the result with the cause. Players are actually more likely to make contact because they are making the plays that lead to winning — they don’t exchange high-fives for a missed dunk or errant pass — but the need to interpret chemistry as something more meaningful clouds the study’s premise.

So, again: why attribute deeper relationships to on-court partnerships? An informal poll leads to a simple answer. “I just like thinking that they get along, that these guys are friends,” says Danny, 29. A longtime Miami Heat fan, he considers the relationship between that team’s former “Big 3” (comprised of James, Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh) as proof that friendships and winning can go hand-in-hand. It’s a reasonable and sincere belief, but still fails to provide any proof. The fly in that particular soup of thought is that James and Wade were close before working for the same employer, remained so even when that partnership dissolved in 2014 and remain so today as newly-formed teammates in Cleveland.

There could be a hint of ancient mythologizing at play, looking to ascribe mortal characteristics to those immortalized on the hardwood pantheon. Just as those myths wove tales of greed, lust and all-too-human foibles, we seek to make the NBA gods better versions of what we are, and what we’d like to be.

Still, there’s a risk involved in attaching too much significance to the arbitrary relationships that are formed and broken with great frequency. Trades (like Irving’s), free agency and any number of activities serve as reminders that league-related business takes precedence over sentimental bonds, both real and perceived. From a fan’s perspective, that is particularly relevant. Players that once shared a workspace might find themselves in opposition — any notions of friendship are expected be suspended for the duration of that contest.

Moreover, if given the choice between an unsuccessful team of friends or a title-contending collection of coworkers, you might find that most fans would prefer the latter. “Hell yeah,” says Danny. “Winning is absolutely the most important part. I’m not about no lovable losers.” Friendships, like many mythological traits of the divine, can be fleeting. A championship, like the one Irving and James made possible in 2016, will last forever.