Premier League: The race for fourth is an everlasting model for the success of soccer

By Kristen Wong

With English teams still fighting for UCL qualification, the competitive model of the Premier League will outlast and prevail over any future plans for a “super league.”

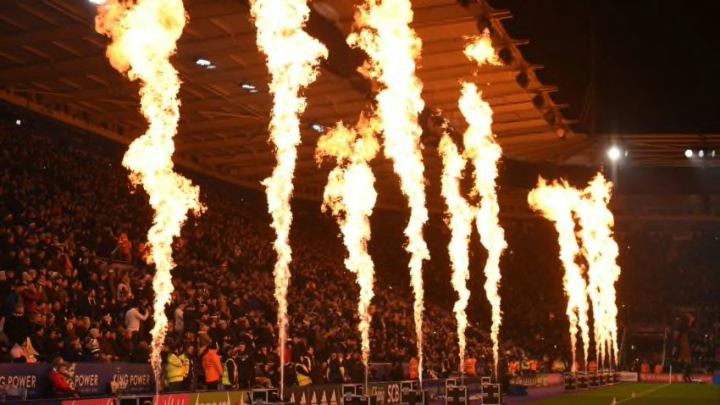

On Tuesday, to very little surprise, Manchester City became 2021 Premier League Champions following Manchester United’s loss to Leicester City. While City have been waiting to clinch the league title for a few weeks now, the United-Leicester match had heavier implications for a different race.

The race for fourth place.

After the win, Leicester jumped to third place with 66 points, albeit with Chelsea close behind (64 points) and with a game in hand of West Ham (58 points). The top-four chase is currently the most competitive clash in the Premier League and for good reason: those four teams qualify for next year’s UEFA Champions League group stages.

With English teams in both this year’s Champions League final (Chelsea, Manchester City) and Europa League final (Manchester United), there is a slim chance that the fourth-place finisher in the Premier League wouldn’t actually qualify for the UCL next year.

Speculation aside, the traditional race for fourth place captures the beauty of the Premier League and that of soccer in general. As an uber-competitive and incentivizing model for teams to finish higher in the table, the race embodies the sport more than any Super League ever could.

Out of everything the near-formation of the Super League got wrong — and this is where Florentino Perez should take notes — thinking that fans watch soccer for the star talent is perhaps the most significant.

Fans watch the sport for the sport itself, and that’s why the Premier League has existed for 29 years and why the Super League crumbled in a little over 48 hours.

Without the dangers of relegation, teams have nothing to lose, and without the diversity of smaller clubs, teams have less to play for. Of course, it doesn’t hurt to showcase skillful players that can razzle and dazzle fans, but without the stakes, the game becomes little more than theatrics; bought-out egos kicking around a lump of cow skin to make money go around.

The stakes for fourth place in the Premier League this season couldn’t be higher. As many as six teams are currently vying for a golden ticket to the UCL with only a few games left in the season. According to data analysts at FiveThirtyEight, Chelsea has a 91 percent chance of qualifying for the UCL followed by Leicester (80 percent), Liverpool (28 percent), West Ham (two percent), and Tottenham and Everton (less than one percent).

Historically, the race for fourth has been competitive ever since England was awarded a fourth berth in the Champions League in 2002. This year, Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s Serie A have their own down-to-the-wire contests, but in those leagues, “premier” clubs would consider it a failure to finish anywhere but first place.

By contrast, Premier League teams aren’t chasing their title dreams, as City all but secured the league weeks ago. Teams are fighting for a measly fourth, which, unless you’re Tottenham, isn’t something to brag about. Yet, the natural-born importance of this race trumps the inflated sense of self-worth of any “super league.”

The race for fourth is a microcosm of high-stakes competition in the Premier League as a whole, but the league’s dog-eat-dog mentality wasn’t actually part of the original intention of its founders. In 1990, a handful of England’s top soccer teams plotted to break away from the Football League, a century-year-old institution that oversaw English soccer, and form their own league. Sound familiar?

Why Premier League is better than any Super League could ever be

In the book, The Club, which details the rise of the Premier League, Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg reveal what was once English soccer’s endlessly tiered ecosystem. Since 1899, England’s so-called soccer pyramid consisted of hierarchies of professional, semipro, and amateur clubs that encompassed thousands of teams stretching all the way down to local pub league players. At the end of each season, the three worst teams are replaced by the three best teams from the division below, and down goes the food chain.

As the top clubs grew in size and reputation, they became frustrated with the turtle-like pace by which other clubs moved and wanted to play in a league of their own. Their plan, as Robinson and Clegg put it, was “to take the English soccer pyramid and lop the pointy bit off.” Their ambitions coupled with NFL-inspired ideas of mass-marketing English soccer gave birth to what we know as the Premier League.

That’s right: the EPL was once as elitist as the Super League.

But whereas the Super League was haphazardly slapped together by the money-grubbing palms of billionaire club sugar daddies, the Premier League was established with posterity in mind. Even with the continued dominance of top-flight clubs, the league’s founders created a lasting framework to keep the bottom-feeder clubs rich enough to play. More important, they ensured natural competition by making relegation a financial catastrophe and, with the later formation of the Champions League, incentivizing top-place finishes.

Fast forward three decades, and the ethos of the Premier League – the rivalries, the relegation drama, the reigning club dynasties – has stayed the same. Some managers have cracked the code to establishing invincible teams (Arsene Wenger), some have suffered barren years of trophy droughts and embarrassing mediocrity (also Arsene Wenger), but no one thought of overhauling the system because it wasn’t broken.

In the modern era, because of the Premier League’s comparative parity as well as brutal competition, star talents like Lionel Messi and Neymar have gravitated toward the monopolies and duopolies in Spain, France, and Germany. Ever since United’s Cristiano Ronaldo left for Madrid in 2009, the Premier League never could brag that it housed the best player in the world.

But that doesn’t mean the league has lost any value. It simply doesn’t have a shining poster boy for the sport, and it can live with that. The league does, however, have something just as unbelievable as superstars’ skills, and it’s as cliched as this: hope.

You need only to whisper “2016” and mobs of Leicester City fans will come running out onto the streets with sloshing pints of beer. That was the year the Foxes, against 5,000 to 1 odds, won the Premier League. Another team probably won’t make the same Cinderella run for decades, but it’s the idea that they could. Every so often fairytale endings do come true, and besides, a league of princes and paupers is wildly more entertaining and unpredictable than a royal court of stiff-nosed blue-blooded nobility.

Even Manchester City, who have won three Premier League titles in the last four years, were once the paupers. Founded in 1880, the club spent more than a century in the shadow of Manchester United’s storied reputation and were best known for winning its first league championship in 1937 and promptly being relegated the following season. Tell that at City’s trophy celebration parties.

Over a century after the Premier League was formed, club owners have once again started dreaming of an even more lucrative “European Super League,” but this time, history won’t repeat itself. Doubters of the game need only look toward the fourth-place race in the Premier League – Chelsea, West Ham, and other contenders who are clawing until the very end to stay relevant, to stay in elite competition.

That England-bred fighting feeling is one the Super League, for all of its artificial glory, could never reproduce, and it’s a feeling that will keep the sport alive and well for the foreseeable future.