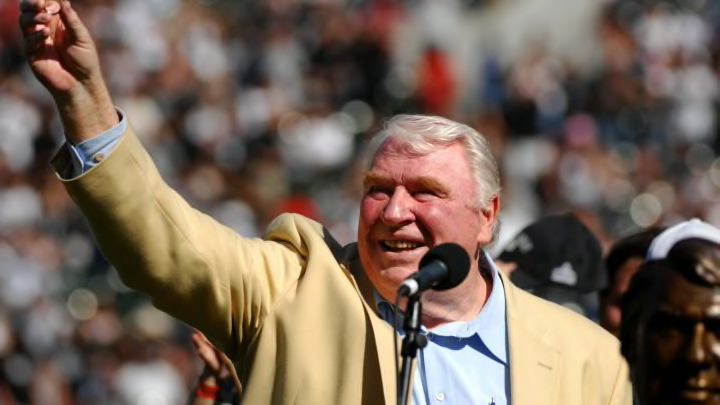

A story of John Madden, a father and son, and a couple of Falcons

Before John Madden was the monarch of NFL broadcasting, he was a seminal part of developing my love for the game of football.

The late John Madden left his mark on the fabric of American football, and beyond his larger-than-life presence on the field and in the press box, he did it through his unknowing effect on individuals like myself.

Before his trademark, “Boom!” became commonplace, before his indecipherable scribbles on the telestrator, and before John Madden was the monarch of NFL broadcasting, he was a seminal part of developing my love for the game, and my passion for a brutally dreadful team.

In the fall of 1978, I was a typical 11-year-old kid. My family had moved from New Jersey to the suburbs of Atlanta when I was four, so for all intents and purposes, I was growing up as an Atlantan.

Little did I know the suffering that was to come in claiming such status as a sports fan, because, like most kids my age at the time, I was into sports. I played little league baseball, driveway basketball, and — of course — backyard football.

The Atlanta Falcons franchise is only a year older than me, and up until the 1978 season, success had been fleeting at best. The Falcons had only two winning seasons prior to that year and had never qualified for the playoffs.

Hence, watching the Falcons was not high on the sports priority list for me, and deciding who I wanted to “be” when playing backyard football in the shadow of Thornhedge Estate’s majestic pine trees usually left me conflicted.

It almost seemed unfair for my fandom to be tied to such a floundering team, but my late father wouldn’t have had it any other way. Through my father’s local civic contacts, I was able to meet Falcon greats such as Tommy Nobis and Wallace Francis. He wanted me to feel a kinship to the team.

Year after year, I was gifted jackets, hats, and shirts bearing the Falcons logo, and week after week, my father worked on indoctrinating me into the subtle art of watching football on television.

The NFL blackout rules for broadcasting games were very different in the 1970s and 1980s as compared to today. There was no NFL Network (or RedZone channel), no satellite feed or streaming to choose your favorite game. You were given what the local network affiliates were allowed to broadcast.

One NFC game on CBS, and one AFC game on NBC, and if your local team was playing a home game it needed to sell out at least 24 hours prior to kickoff for it to be broadcast in your region.

Needless to say, watching the Falcons play at home on television was a rare occurrence, and on the off chance the game did sell out and was broadcast in the Atlanta area, it was never the premier game of the week featuring the network’s top broadcast team.

In 1978, all that changed.

That was the season the Falcons were thrust into the national spotlight, and fans began packing the all-purpose flying saucer known as Atlanta Fulton County Stadium on a semi-regular basis. Names such as Steve Bartkowski, Wallace Francis, Claude Humphrey, and the famed Grits Blitz defense started to become frequently heard on television.

John Madden, my father, and Sunday football

After making the playoffs and nearly defeating the mighty Dallas Cowboys in the NFC divisional round, two things happened the following season.

The Falcons crashed to earth in a 6-10 campaign, and CBS hired John Madden as a color commentator.

Both parties were on their way up.

In 1980, expectations were high for the Falcons to bounce back, and John Madden began making his name as the most knowledgable and affable personality there was in the broadcast booth. CBS paired Madden with a number of play-by-play partners, and they were generally given some of the lower-profile games each week.

Low profile? That fit the Falcons perfectly.

Something else happened in 1980 as well. 1979 third-round pick William Andrews had emerged as a premier running back in the league, rushing for 1,023 yards in his rookie season (one of the few highlights that year) and he was paired in the Falcons’ backfield with a fourth-round pick, Lynn Cain.

Those names would become not only important in Falcons’ history but also footnotes in the mystique of John Madden.

Being a Falcons fan wasn’t quite as painful at that time, and getting to see them on television every week (as opposed to just the road games) gave me extended bonding time with my father, which he took advantage of in trying to school me on the finer points of football.

The recipe was perfect. A father and son reveling in the success of a long-suffering team, and a budding broadcaster who — more often than not — had the job of analyzing what that team was doing on the field.

“Listen to what Madden just said”, my father would often exclaim. “If you want to understand this game, you need to listen closely to him.”

And I did. Anytime John Madden spoke, I was listening. He was vivacious, fun, smart and simply had a way of connecting with viewers. I was into football prior to becoming a fan of John Madden’s work. Once he entered the picture, I was a fanatic. His influence went beyond just teaching me a greater appreciation for the game.

As the Falcons showed more and more during the 1980 season that they were a team to be reckoned with, John Madden latched on to an idea when he was calling their games.

He singled out the two Atlanta running backs Andrews and Cain time and time again, saying (loosely quoted) “If I were going to start my own team and could pick any players I wanted, I would start with these two guys.”

Yes, what you just read was the humble beginnings of “All-Madden”, and it felt almost surreal to hear someone as deeply ensconced in the game of football and the NFL heap such praise on two Falcons. It made backyard football role-playing quite simple, too.

I’d watch the game with dad, and then afterward, grab a handful of friends to live out our own fantasies of de-cleaters and long bombs.

Unashamedly, I was William Andrews. I crushed people when I ran over them, and John Madden’s song of laudation resonated in my head as I buffaloed my way towards the mimosa tree that marked the end zone.

“Boom! Did you see that? He just flattened that kid. Look at the dirt and grass clumps on his jeans there. Now, that’s football.”

During weeks that Madden was handed other games to call, I felt cheated. Watching the Falcons was a different even lesser experience without him. My father felt it too.

As the years moved forward, the Falcons returned to mediocrity, and Madden was paired with Pat Summerall as the top-tier NFL broadcast team for CBS. I didn’t get to see a lot of Falcons wins, but I did get to hear John Madden every week, and every week that was done sitting with my father.

As broadcasting began to evolve and technology improved, there was always a constant. John Madden was going to make the game you were watching an experience. We loved it and loved him. Madden was so mesmerizing, that even my mother became enamored with his work. If she found out another pair was calling the game, she’d quickly become disinterested in watching.

Growing up football in the Collins house not only included John Madden, but in many ways, it depended on him.

In 1985, my father unexpectedly died. While he was the one who ignited my love for football, it was John Madden who perpetually added fuel to that passion. Sadly, I never met him, shook his hand, or told him that he had become an instrumental influence during my formative years.

I wish I had.

I wish I had just once been able to look at John Madden’s gentle giant face and tell him that he helped strengthen what was already a powerful bond between a father and son. I wish he knew that hearing his voice on television through my growth as an adult carried me back to the living room and Zenith console television on Thornhedge Drive while sitting across the coffee table from my father.

Maybe he knows now.

Thanks, John, for helping make my childhood great. I think I’ll go to my backyard and do a fat guy touchdown spike in your honor.

Boom.

dark. Next. 5 times Madden proved he was the GOAT of broadcasting