In wake of Davide Astori’s death, Stefano Pioli demonstrated the value of mindfulness

Sunday, March 4, 2018 was the darkest day in the history of Fiorentina. That morning, club captain Davide Astori wasn’t the first person down for breakfast as he normally would be before an away match. There was no answer to a knock on the door of his room, and he was eventually found dead in his hotel bed ahead of Fiorentina’s fixture with Udinese.

“I arrived in front of room number 118 in my pyjamas, [goalkeeper Marco] Sportiello was already there. ‘Mister, Davide is gone’ he said. But I still did not understand,” confessed Viola boss Stefano Pioli in a revealing interview with local newspaper Corriere Fiorentino at the time.

“Then, opening the door I saw [Alberto] Marangon and [doctor Luca] Pengue crying and Astori there, lying on his bed. It seemed like he was sleeping, but it wasn’t so. The most difficult moment was going around the rest of the rooms to tell the rest of the team what had happened. It was something that I would not wish on anyone.”

If this was an event that shocked the entire world of football, consider the earth-shattering impact on the close-knit inner circle at Fiorentina. This group of players had lost their leader, a man described as kind, welcoming and wise by all those who knew him.

Pioli was hurting too, and many others would have walked away from, or simply crumbled under the pressure of a situation in which the world’s media was focused upon their grief. Instead, he gathered his young squad under his wing and supported them through a public funeral and the following home match, all within the space of a week.

The players returned to training on the Tuesday after Astori’s death, and it was then that the coach admits he recognized things would never be the same for Fiorentina. “Initially I feared for my players,” he continued in that same interview. “On the Tuesday when we restarted training, it was hard. So many of our youngsters had not even properly realized what had happened.

“To get changed, to work, to train without Davide that afternoon created a sense of emptiness in us all. I started to speak, then I asked who felt like they would like to say something. All those who did so said to me ‘we want to carry on with the values that Davide stood for, we want to do it for him. With gratitude and affection.’ At that moment I understood that they had the strength to start again, I understood that something had clicked. Personally, however, I still struggle without him.”

Whether he realized it or not, the experience Pioli described was strikingly similar to the process of being “broken open” outlined by Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee, a teacher of a branch of Islam named Sufism, in the book The Wisdom of Sundays.

“Yes it is painful,” he says. “One has to learn humility. You have to learn patience. You have to learn that it isn’t all about you. And those are all painful lessons. There is a crucifixion of the ego, then the heart breaks, and God says “I am with those whose hearts are broken for my sake.”

The tragedy would’ve shattered a lesser man, but instead the Fiorentina coach found inner fortitude that allowed his players to lean on him for support. Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk explains in his book Living Buddha, Living Christ that the presence of such a pillar of strength like Pioli in that moment should be seen as a precious gift.

It’s a theme that runs through the Buddhist tradition of mindfulness and the Christian idea of the Holy Spirit, as Hanh explains: “Mindfulness relieves suffering because it is filled with understanding and compassion. When you are really there, showing your loving-kindness and understanding, the energy of the Holy Spirit is in you.”

Managing the crisis as it happened was one thing, but how did Pioli and his players move forward in the long-term? To find out the answer, it’s important to take a step back in time and look at the tenure of Pioli’s predecessor, Paulo Sousa, and to examine the ways Pioli has reversed so many negative trends established under him.

Appointed in June 2015, Sousa had a history of bad relationships with club owners. Good results convinced Fiorentina supporters to overlook his past as a player for hated rivals Juventus, as the Viola moved to the top of Serie A for the first time since 1999. However, such joy was short-lived, and it quickly became clear any short-term success was a fluke. Sousa’s propensity for changing both tactics and personnel in each and every game was an indicator of his total ineptitude.

In order to cover for those shortcomings, the Portuguese revealed his true colors as an abrasive excuse-maker, and would become embroiled in altercations with the press and club officials alike. Sousa’s relationships with team manager Vincenzo Guerini and communications director Elena Turra became untenable, and — by refusing to play talented new signings Riccardo Saponara and Marco Sportiello — he eventually incurred the wrath of sporting director Pantaleo Corvino.

Fiorentina supporters were certainly glad to see the back of Sousa, but were not much more impressed by his replacement, Pioli, a man with a reputation as a distinctly average coach. There were protests over a fire sale of well-loved and experienced players that summer, but an entirely new project with younger replacements would lead to a clean break from the negative energy created by the former boss.

In his opening press conference, Pioli revealed his upbeat and positive nature. “I don’t know if my face is doing justice to just how happy I am,” he told reporters that day. “I’ll give my all. It’s easy to make promises but they can be problematic. One thing I can say for sure is I’ll put in a lot of hard work and a lot of passion. We’ll try to do a good job and to give fans what they deserve.”

Despite being quiet and pensive in public, Pioli didn’t take long to forge this group of young men into a unit, and it was clear his outlook was nothing like that of his predecessor. He placed inspirational quotes from former club heroes such as Roberto Baggio and Gabriel Batistuta on the dressing room walls, while refusing to continue the trend of blaming others for poor results.

A perfect example came after a narrow loss at the hands of last season’s Serie A runners-up. “I think this defeat is more our fault than giving credit to Napoli,” he told reporters shortly after the final whistle. “We tried to take the initiative, but could’ve done more and created more problems for their defense. Errors can happen, but the important thing is never to settle, always go for the victory.”

Pioli’s willingness to take ownership for bad results rather than seeking a scapegoat plays into a theme explored by Jack Canfield in the Chicken Soup for the Soul series of books. “Every time we are negative about someone else, we are actually affecting ourselves,” the author said in an interview with Oprah Winfrey. “So basically, the old thing when you’re pointing the finger, there’s three fingers pointing back. So I always tell people that whatever you focus on, you get more of.”

This outlook mirrors what the coach was trying to achieve in those early days, a modern take on the Buddhist tradition of Karma. This is an often misappropriated word that refers to action driven by intention, something expressed either outwardly or inwardly that leads to future consequences.

Putting feelings of self-importance aside is an essential part of any tangible glory in a team sport and is something that Phil Jackson discussed in his book Eleven Rings, The Soul of Success. A self-confessed follower of Zen Buddhism, the legendary basketball coach writes about “benching the ego” and the premise that practicing mindfulness allows a team to master the game from the inside. He discusses the way teammates can bring about the “best nature” in each other, thus manifesting an elevated spirit in those who watch them.

The “ego” referred to by Vaughan-Lee and earlier by Jackson is what most people think of as the part of us that is boastful and full of false pride, but in this sense it means much more. Zen Buddhism advocates the death of the ego, the part of us that emphasizes our separateness from others.

Sousa was a superb example of a man in full grip of his ego — thoughts such as “it’s not fair” and “why should I?” dominated his outward behaviour. “This sense of separation [from others] is an intrinsic part of the ego,” writes Tolle. “The ego loves to strengthen itself by complaining — either in thoughts or words — about other people, the situation you find yourself in, something that is happening right now but ‘shouldn’t be,’ and even about yourself.”

If anyone had an excuse for the poor results that could have followed Astori’s death, it was Pioli. Yet he taught himself and the players around him to put their individual pain and ego to one side, to find solace in pulling together and achieving something for the captain and friend they had lost, and learning from his example.

“He always found the right way and time to say things. He was generous, positive, altruistic,” Pioli told reporters in his press conference before the first match played after the tragic loss. “I usually like to motivate players by telling them: ‘Try to train and play as if it was the last time.’ I never needed to say that to Davide. He has left us so many values, that seed of passion, professionalism and sensitivity. Now it’s up to us to look after it and help that seed grow. All united, in memory of Davide.”

Pioli may not have realized that his actions were so in-keeping with what is taught by Buddhism and other spiritual principles, but the matches following that tragedy highlighted exactly how they had worked.

After expending a superhuman amount of energy in that first home game versus Benevento, the emotionally exhausted players went away with a 1-0 victory. Four consecutive wins and a draw would follow. “We were playing good football even when Davide was with us, but we lacked consistency, which is also normal given the changes that we had made,” Pioli admitted to RAI radio after that run. “Now we are more of a team, more mature and the results are arriving. We’re reaping the rewards of a very long but positive job.”

If ever there was a blueprint for other bosses to follow surrounding accountability and the avoidance of excuses, this was most certainly it. There are football matches where tiki-taka or gegenpressing have secured a victory, but in the aftermath of Astori’s death, Pioli’s mindfulness made the world of difference for Fiorentina.

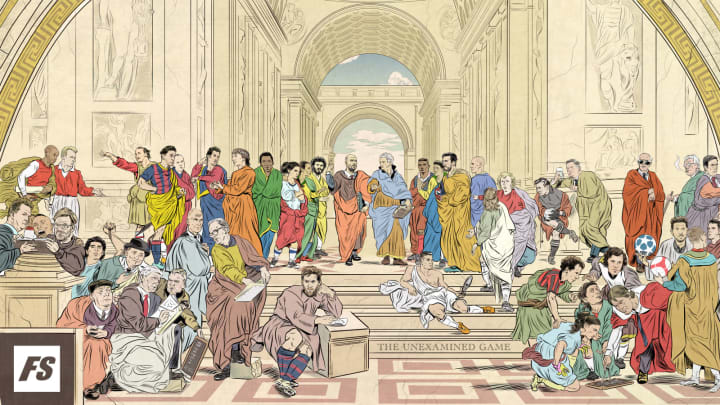

The Unexamined Game is a new series exploring the intersection of philosophy and football. You can find the previous articles in the series here:

Toward a philosophy of football

Pep Guardiola, tiki-taka and the end of football