In the beginning, it was a cross.

There was Ronaldinho, 40 yards from goal, eyeing the line of players at the top of the England penalty area, every last one of them expecting a ball into the box. And a moment later there was that ball, apparently changing its mind in mid-flight, floating for the better part of forever over David Seaman’s head, before finally dropping in at the back post.

The goal was labeled a freak, the free-kick a botched cross, Seaman an embarrassment. Asked after the match by Rio Ferdinand whether he meant it, the Brazilian shrugged his shoulders, smiled. This was taken by England’s players as yet another piece of evidence he didn’t mean it, couldn’t have possibly, although if you had just been knocked out of a World Cup quarterfinal, would you rather blame bad luck or your own inferiority?

A year later, nobody the wiser, Ronaldinho moved from PSG to Barcelona, and within a couple of seasons had become the best player in the world. And not just any best player in the world, but a player who seemed to have been put on this earth specifically to do the opposite of what was expected of him. The sort of player you watched not to see where he was going (which you already knew was wherever he wanted) but simply how he would get there, joga bonito made flesh.

Knowing what we know now, then, that free-kick plays a little differently. There was Ronaldinho, the greatest player in the world playing for the first time in his career on the sport’s biggest stage, 40 yards from goal, knowing full well everyone was waiting for a ball into the box. And so it was that his cross, several years after the fact, began its second life as a shot.

The only problem with this story is Ronaldinho’s version of it. In 2003, he told reporters he was shooting, but was aiming for the other side of the goal — which, well, no one wanted to hear that, the worst of both worlds. And so what many people did is they didn’t, just up and ignored him, leaving the rest of us with this question: Who should we believe, Ronaldinho or the ball?

This is football’s problem of other minds.

Philosophy’s problem of other minds is this: Since we can only observe the behavior of other people, as opposed to the thoughts running through their heads, we can’t be sure there are any thoughts running through their heads at all. Maybe they are all behavior.

Football’s version of this problem is only a distortion of the original. It isn’t that we’re unsure whether players have inner lives — quite the opposite, we take it for granted they do — but that we take the flight of the ball they kick around as unproblematic evidence for what is going on there.

There are of course extreme cases, like Ronaldinho’s free-kick, in which the flight of the ball is insufficient evidence to determine what is going on in the mind of the player who kicked it. The point of this piece is to suggest those cases aren’t so extreme as we tend to think.

~

Consider, for example, Daniel Sturridge’s equalizer for Liverpool against Chelsea at Stamford Bridge in September. This is how seven different writers, writing for seven different outlets, described the goal:

1. “Sturridge snatched a draw in memorable style as he curled a left-footed shot over Kepa from 30 yards out.” James Walker-Roberts, Sky Sports

2. “Sturridge, with as much nonchalance as brilliance, looked up and sent a 25-yard finish in an arc past the stretching Kepa.” Phil McNulty, BBC

3. “From an improbable angle and distance, he offered an improbably impressive shot into the top corner, that left Kepa Arrizabalaga flailing and Sturridge’s old club deflated.” Miguel Delaney, the Independent

4. “All seemed lost for Liverpool, who had created half a dozen clear chances and squandered all of them, when the 29-year-old stepped up with a minute of the game to run. The goal that ensued will live long in the mind’s eye: a looping shot from 30 yards casually despatched from the left instep which soared above Kepa Arrizabalaga and into the net.” Ian Herbert, Daily Mail

5. “His equaliser was a magnificent goal, the kind of strike from distance of a still ball that would have been impossible for any goalkeeper to save.” Sam Wallace, the Telegraph

6. “There were two minutes of normal time remaining when Daniel Sturridge … let fly with an elegant swish of his left boot. … before Sturridge deceived Kepa Arrizabalaga, the Chelsea goalkeeper, with the swerve and trajectory of his high, angled shot.” Daniel Taylor, the Observer

7. “Liverpool were able to bring genuine strength from the bench, Xherdan Shaqiri missing the chance to level the score, then Sturridge taking it with a stunningly conceived dipping shot — a moment of brilliance pulled out of the air in the most taught and congested finales.” Barney Ronay, the Guardian

There are two distinct approaches here, each exemplifying a different side of the same problem. The first, what we might call the standard approach, is perhaps the most dominant in all of English language football writing: “curled a left-footed shot,” “sent a 25-yard finish,” “offered … an impressive shot into the top corner,” “casually despatched … a looping shot from 30 yards.”

This formulation is so pervasive the words themselves feel almost beside the point. The effect is to dull the senses, to put the mind on autopilot. They are all meaning, no saying.

This is not a matter of good or bad writing (I have written enough sentences like this to insulate entire homes, and besides, woe betide the writer who has to cover a last-minute equalizer on deadline). The question is whether our language is equipped to do what we want it to do here, to get to the heart of the matter, which is that somehow Sturridge was responsible for an extraordinary event that took place 30 yards away from him. If there’s an underlying question here, it’s this: In what way was Sturridge responsible for the goal?

The problem with the standard approach is not that it is lazy or artless, but that it seems to pluck the inspiration away from the player and award it to the ball instead. The shot is “magnificent,” “impressive,” it “soars” and “loops” and “arcs”; the player merely “sends,” “offers,” “curls,” “strikes.” There are perhaps more exciting verbs we could choose from — ping, uncork, smash — but the structure of the sentence necessarily privileges the ball.

Is this an unavoidable byproduct of the fact a player’s foot, when he shoots, is in contact with the ball for only a very small fraction of a second? That ball is then in flight for considerably longer, long enough to do all sorts of the weird and wonderful things we take such great pleasure in describing — hang and swerve and whizz and fizz and dip, etc.

Some of these verbs can be, for lack of a better term, given to the player, e.g., “Sturridge fizzed a shot,” but only some of them. “Sturridge swerved a shot” doesn’t quite work, though “Sturridge sent a shot swerving” does. Not that this solves the problem. Because for all the flaws of the standard approach, it feels true, it jibes with our experience of the game.

Indeed, watching a ball do these things, it’s remarkably easy to forget about the players entirely, to remember them only after we’ve seen what the ball has gotten up to on its own. We marvel at their skill and creativity, but not even the greats can hold us in thrall quite as reliably as a ball in flight. For when the ball is in the air — when it does not, as it were, belong to anyone — everything remains possible.

We crave precision, skill, quick passing, movement, but I sincerely doubt there’s a purer source of footballing excitement than a keeper dumping the ball 80 yards up the pitch with his team trailing by a single goal. Those few seconds, between his kicking the ball and its arriving in the throng of bodies in the box, seem to contain the entire mystery of this sport, its deepest, darkest secrets.

Of course, as I’ve already suggested, we also think of a shot as in some sense belonging to the player who took it. That is, he is responsible for its magnificence (or whatever else). But the specific nature of this ownership is surprisingly hard to pin down. Consider the sentences above that deliberately avoid the standard approach: “with as much nonchalance as brilliance,” “let fly with an elegant swish of his left boot,” “deceived Kepa … with the swerve and trajectory of his high, angled shot,” “a stunningly conceived dipping shot.”

Each of these, in one way or another, attempts to make explicit Sturridge’s responsibility for, his ownership of, the shot: He, not the ball, deceived Kepa, the shot wasn’t magnificent, but stunningly conceived (i.e., brought about by a specific mental process), the result of an elegant swish of his left boot. If the problem with the standard approach is that it fails to give the player the credit he deserves, the problem with this latter approach is that it risks minimizing the importance of the ball.

But the ball clearly is important, where it ends up matters to us. It changes the way we talk not only about the player who kicked it, but the way he kicked it. Indeed, Sturridge has attempted many similar shots in the past that have not ended up in the top corner, have in some cases not ended up anywhere near the top corner.

But his thought process in those instances, even his technique, was presumably more or less identical to what it was against Chelsea. Which leaves us in the strange position of having to admit that we called Sturridge’s shot stunningly conceived, the swish of his boot elegant, only because the ball ended up in the back of the net. But surely the shot was either well-conceived or it wasn’t. He either swung his boot elegantly or he didn’t.

This last point is in general something we seem to understand. Consider, to use one particularly famous example, Pele’s shot from the halfway line against Czechoslovakia at the 1970 World Cup. It says something that one of the most celebrated moments in the history of the sport is a shot that didn’t even hit the target. It says that ideas matter, that what a player thinks can be just as important as what he (or at least the ball) does.

But this is true only up to a certain point. If Pele had sliced his shot out for a throw-in, as opposed to drilling it narrowly wide of the post, it’s hard to imagine we’d still be talking about it 50 years later. I want to suggest we’re veering toward contradiction, or at least confusion, here. Surely the idea (which is, after all, what we’re celebrating) would have been just as audacious, just as powerful a representation of Pele’s unique footballing mind, if he had completely botched the execution. Then again, there would be no unique footballing mind, no audacity to speak of if Pele wasn’t a player who successfully executed his ideas most of the time. If a player only ever failed to execute ambitious ideas, we wouldn’t celebrate his audacity; we’d just call him bad.

~

It seems, then, we are trapped. On one side there is the player, or at least the player’s body — his position on the pitch in relation to his opponents, his technique as he kicks the ball, even the things he has done in the past. On the other side there is the ball, living in 90 minutes more life than many of us will manage in 90 years — screaming from one side of the pitch to the other, flying into top corners, squirming under tackles, slicing out for throw-ins, floating for so long over David Seaman’s head the poor bastard is forced to retire.

Unsure where to look, we’re left with a sort of endless, increasingly rapid toggling between player and ball, player and ball, player and ball, as if we hope the two might eventually blur together, like the pages of a flip book, to reveal a human mind.

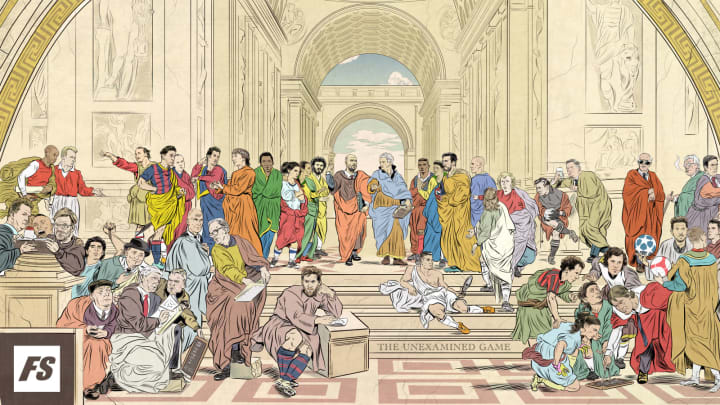

The Unexamined Game is a new series exploring the intersection of philosophy and football. You can find the previous articles in the series here: