“This was how I learned what happened to me, sitting at my desk reading the news at work.”

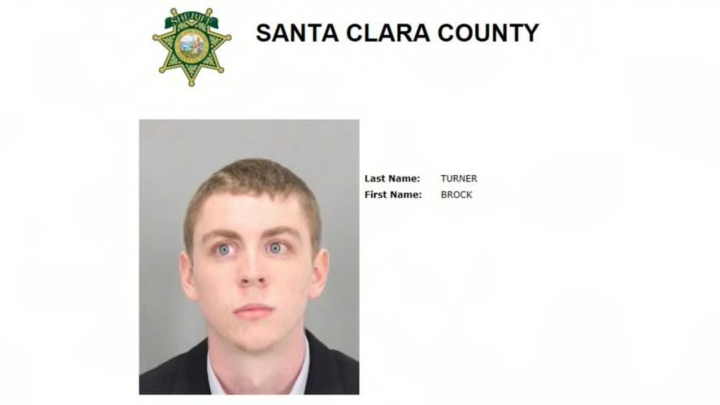

These are the words of the woman Brock Turner, a former Stanford swimmer, raped in January 2015. She is referencing that assault. Turner was convicted back in March. On Thursday, the woman stood in a courtroom and read aloud to both the court and Turner a long piece. In it, she detailed the impact of the assault, which took place behind a dumpster as she lay unconscious before two passersby intervened.

It’s a harrowing piece about the hell of waking up in a hospital without knowing why you are there, but seeing on your body the physical signs that point to a stranger’s violation of it, of you. She left the hospital knowing only that she “had been found behind a dumpster, potentially penetrated by a stranger, and that I should get tested for HIV because results don’t always show up immediately. But for now, I should go home and get back to my normal life.”

And she tried, in part by not verbalizing what had happened to her, not discussing it with her family and friends because “if I told them, I would see the fear on their faces, and mine would multiply by tenfold.” She told Turner and the court that she stopped talking, eating, sleeping, and interacting, and “after work, I would drive to a secluded place to scream.” For more than a week, she had no confirmation from anyone that what she had been told at the hospital was true. Then she checked the news.

“One day, I was at work, scrolling through the news on my phone, and came across an article. In it, I read and learned for the first time about how I was found unconscious, with my hair disheveled, long necklace wrapped around my neck, bra pulled out of my dress, dress pulled off over my shoulders and pulled up above my waist, that I was butt naked all the way down to my boots, leg spread apart, and had been penetrated by a foreign object by someone I did not recognize.” Then “I read that according to him, I liked it.” She was at work, trying to do what the people in the hospital told her, get back to her normal life, when she read about herself online. That was terrible and surreal.

Here’s the part, though, that matters for this specific site and its focus on sports. She said, “after I learned about the graphic details of my own sexual assault, the article listed his swimming times.” After noting how the probation officer for the case made sure to note that Turner “has surrendered a hard-earned swimming scholarship,” she said: “how fast Brock swims does not lessen the severity of what happened to me, and should not lessen the severity of his punishment.”

When an athlete is accused, charged, arrested or convicted of sexual assault or rape, their athletic ability and the potential damage to their career should not be the focus of our coverage.

I write on the intersection of sport and sexual violence a lot. As a result, every once in a while writers and journalists who are new to that intersection ask me for advice. While I have a series of things I say (things I have written about before), the most important is always this: survivors of sexual violence will most certainly read your words, and there is always a chance one of them will be the survivor whose case you are covering. Write knowing that.

As I’ve said before on this site, we are taught to write and consume stories about athletes in a way that focuses on their athletic achievements, even when those athletes are perpetrators of violence. Their talent is positioned alongside their potential for harm as if somehow the two are related, as if the loss of their ability to compete is comparable to the loss of another person’s safety, consent or control over their own body and life.

In a courtroom on Thursday, the woman who Brock Turner raped told her attacker, “In newspapers my name was ‘unconscious intoxicated woman,’ ten syllables, and nothing more than that. For a while, I believed that that was all I was. I had to force myself to relearn my real name, my identity. To relearn that is not all that I am. That I am not just a drunk victim at a frat party behind a dumpster, while you are the All-American swimmer at a top university, innocent until proven guilty, with so much at stake.” (Side note: please read Stacey May Fowles’ on the phrase “innocent until proven guilty”).

But she was also speaking to us, those who write the stories about rape victims and the people who rape them.

In March, when Turner was convicted, Michael Miller wrote a piece about it for the Washington Post. In it, Miller wrote things like, “Turner was a member of Stanford’s varsity swim team, one of the best in the country. He was an All-American swimmer in high school in Ohio, so good that he tried out for the U.S. Olympic team before he could vote. Suddenly he was accused of rape.” He told us, “With sentencing June 2 and an appeal possible, Turner’s once-promising future remains uncertain. But his extraordinary yet brief swim career is now tarnished, like a rusting trophy.” And, “But on Jan. 17, 2015, midway through his freshman year and first swim season at Stanford, Turner’s life and career were upended during a night of drinking.” Miller also quoted several internet commenters to show the differing responses to the conviction; some of them blamed the victim because she had been drinking.

It was a head-scratching write-up about a convicted rapist. Miller repeatedly used the passive voice when talking about the violence Turner did (something experts have studied because of its damaging effects and its prevalence in sexual assault coverage). He also found space to quote non-experts, who blamed the victim even in the wake of a resounding guilty verdict (not that victim blaming from experts would have been okay, but there was something particularly jarring about seeing it from random nobodies in the text of an article in the Washington Post).

At the Cauldron, Julie DiCaro responded to Miller’s post, calling it “one giant head-shaking missive about how disappointing it is when a bright, young athlete ‘suddenly’ finds himself accused of rape — as if he had no active role in the matter.” The Onion took on this trope back in 2011 with a video titled, “College Basketball Star Heroically Overcomes Tragic Rape He Committed.” And yet here we still are.

I emailed Miller back in March, and laid out my issues with his piece. He told me, “I don’t think the article denies his agency, responsibility or criminality, as determined by the court. But your wise and welcome criticism does make me think I could have handled some parts of the article differently.” That’s good.

But the woman’s letter makes it clear just how damaging our coverage of sexual assault and rape can be. The way we center the accused or convicted, the way we glowingly trace the arc of his athletic career, the way we worry about the damage his own behavior may cause to that career — these things matter in real ways that reach beyond our own participation in a culture that already minimizes, and often simply ignores, the problem of sexual violence. It can affect the way a survivor understands their place in this world, and that must give us pause before we sit down to write.

In the end, despite this woman’s compelling and brave account of the impact this crime had on her, and the gravity of the counts on which Turner was convicted, Judge Aaron Persky sentenced Turner to only six months in county jail followed by probation. Turner did not get a harsher sentence because Persky felt “a prison sentence would have a severe impact on him” and Turner will not be a danger to others. This was based on the recommendation of the probation officer, who, the woman noted, seemed to think Turner’s swimming ability should play a role in his sentencing.

In her statement, the woman said, “the probation officer’s recommendation of a year or less in county jail is a soft timeout, a mockery of the seriousness of his assaults, an insult to me and all women.” A day before the sentencing, in a local paper, Scott Herhold advocated for the probation officer’s recommendation because, he argued, “The probation people cite his lack of a criminal record and what they see as genuine remorse. His attorneys have argued that the ex-swimmer has a record of real accomplishment.” The mockery and insult, for sure, is not limited to the courtroom.