“Dad, please don’t go.”

This was something I said every other weekend for a period of two years, watching my father’s 1988 brown Ford Ranger truck back out of our curved driveway in Livingston Manor, NY. I was six and seven years old then, and seeing those taillights fade into the distance was a knife to the heart every time.

Prior to him taking a job in Washington D.C., our autumn and winter Sundays consisted of watching football. As misplaced Kansas City Chiefs fans in a tiny New York town, seeing our team was difficult. Before NFL Sunday Ticket became prevalent in the new millennium, we hoped for the occasional national broadcast.

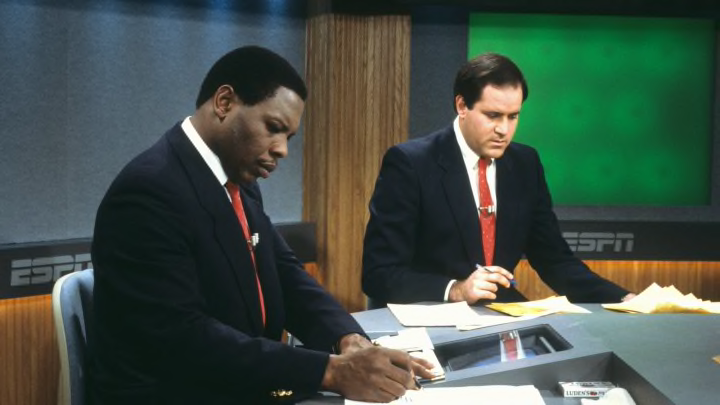

Regardless, we had our savior on Sunday night at 7 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, with hosts Chris Berman and Tom Jackson welcoming us into ESPN’s NFL Primetime.

With my old man a world away, this hour was our lifeline. I learned to find the show on channel 10. I learned to call at 8 o’clock. I learned what it meant to be his son. For me, NFL Primetime was a savior, a way to make 328 miles disappear four months out of the year.

For others around the country, the show was 60 minutes unlike any other, capturing the imaginations of millions. It changed the way America viewed football, ushering in an era of smarter fans who demanded more out of NFL coverage.

NFL Primetime was a cultural phenomenon. The show almost never happened in its known form, save for a ground-breaking idea and an interview taking an unlikely turn. Jackson and Berman. Two people from distinctly different backgrounds, forging a new path in uncharted waters.

The sports world was a different place in 1987. It was about to be a year of turmoil for the NFL, which would see replacement players for the only time in its history. A 15-game schedule was coming as a result of the players strike, but that didn’t deter ESPN from continuing to build its ever-growing portfolio.

With ABC’s Monday Night Football at the peak of its powers, the executives in Bristol, Conn. wanted to expand the notion of pigskin in primetime. The cable juggernaut struck a pact with then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, launching a new project.

On Sept. 13, 1987, ESPN debuted NFL Primetime, with permission from the league to lift its restriction on highlights. The Sunday Night Football package began once the World Series ended, with Primetime acting as a bridge from the late games.

“I have to give credit to Rozelle, who was brilliant, and our president, Steve Bornstein,” Berman said. “They invented the show. It was a very big step-out for the NFL. … We had the rights to show 60 minutes of highlights. We were allowed to do it. The way it was told to me is ‘Rozelle thinks it’s a really interesting idea’ and Bornstein said we’re going to throw it, and I’ve got the guy to throw it.”

The idea was revolutionary. Most fans’ only exposure to highlights beyond their local teams was Monday Night Football’s halftime show. In a matter of minutes, commentator Howard Cosell would zoom around the league with words dripping in accent and bravado, showing a play or two from the week that was. In many instances, only a handful of games were touched upon.

When ESPN unveiled NFL Primetime, it was the sports equivalent of going from the stone age to the space age.

“Having grown up living and dying with Monday Night Football halftime highlights, it was the next generation,” said Don Banks, longtime Sports Illustrated and NFL beat writer. “It was the kind of thing that if you sat there for an hour you could see everything of significance that happened in the NFL. I do think it’s responsible in part for some of the growth of the game.”

Behind the scenes, production assistants had specific assignments. They were to create a highlight package for one game, hopefully ending with the approval of Jackson and Berman. Each highlight was supposed to tell the story of what unfolded, including tackles or dropped passes that quietly helped shape the result.

When all was set and done, the talent was given a shot sheet, detailing the order of the games and the plays covered in each. The duo watched each early-game package once, if at all, before going live. The late games were seen by Berman, Jackson and the fans for the first time, at the same time.

“For Countdown or GameDay, you worked six days to prepare for the hour,” Berman said. “On Primetime, you did nothing until the ball kicked off at 1 o’clock. You had six hours to do your hour. It was the closest studio show ever — and I would challenge anyone doing it now to say otherwise — to doing a live game.”

In a typical show, Primetime would begin with Berman reading off the late-game scores, letting the viewers know the standing of games in progress. From there, Primetime weaved through the early contests, allowing each to unfold without revealing the ending. The highlights were shown chronologically and over a period of minutes, not seconds.

For the first time, the American viewing public was exposed to the bones of a scoring drive, not simply the conclusion. It was the narration of what happened, not a synopsis of what you needed to know.

“The beauty of the show was it wasn’t 30 seconds of each game,” Berman remembered. ” … I already saw that. In a four-point game, in the mud, third and 3, with 1:40 to go, here’s the tough 4-yard run that got the first down and essentially won the game. Here’s the sideline-to-sideline tackle made by Junior Seau or Lawrence Taylor. In those days, you didn’t see those because it was just a really good tackle, it wasn’t a scoring play. We had 5-6 minutes on each game. If you lived in New York, you didn’t see any of this. … It was an empty pool and we jumped head-first into it.”

For all of his jokes, Berman’s legacy is his underlying work ethic.

Berman, a Jewish kid who found his way to the fledgling television network back in 1979, would become the epicenter of a cultural movement eight years later. Until the birth of NFL Primetime, must-see programming was reserved for sitcoms, the six o’clock news and live sporting events. For a legion of reasons, none larger than Berman’s persona, that soon changed.

While viewers saw the character with nicknames aplenty, the show’s success was built on hours of preparation put in by Berman, Jackson and the crew. Without a script and on live television, we saw the true brilliance of this pairing, helped by a non-existent safety net. Most would loathe being in this position even once. Berman was there hundreds of times, with the outcome seeming effortless.

“Chris would do the pregame with all the guys and that would end at one,” said Bill Pidto, a co-host of the show in 1995-96. “I would come in at one o’clock and we had a room where every single game was on and you’re just reacting to everything happening in all the games. At four the early games end and you have a sense of what is going on, but the challenge was the late games end while you’re on air, so you might have a real good feel for the early games but the late games are ending 7:15 or 7:30 and you’re winging the whole thing. That’s the beauty. That’s Chris Berman’s genius. He was making it seem like he saw the whole thing.”

Throughout the show’s run, Berman became notorious for tardiness. It was a routine, watching the highlights and getting the latest information before plopping down on set.

“The theme song would play and I’d be running into the studio sometimes,” Berman said. “Sometimes I didn’t have the mic on and I had to hold it against my tie.”

In many respects, Primetime was a studio show mimicking the production of a live game. In this vein, the cohesiveness of Berman, Jackson and the production crew had to be flawless. It wasn’t always the case.

“Jeff Winn was our first director,” Berman said. “The producer and director are usually together and the producer and talent are together. But this is like a live game, and the director and the host have to be on the same page. I used to jokingly say let’s not let the puck get past us. So one show, we were running a bunch of things and Jeff would come into my ear and go ‘I think they got one by us.’ Then there were other times when I’d hit the mute button and say ‘they hit the post twice but it didn’t go in.'”

The program was a breeding ground for not only new fans, but television personalities. Pidto was one of many to get their big break on Primetime. He was preceded by John Saunders and Robin Roberts, and succeeded by Stuart Scott. Both Pidto and Scott notoriously got stuck with the worst games of the week, something Primetime made into an inside joke for viewers.

“It was an amazing experience,” Pidto said. “The show starts and the music begins and you feel like you’re in the biggest place in the world at that time. For what we did that was the biggest stage in the world at that time.”

For Berman, sticking the newbie with a Buccaneers-Bengals game was a way to have a chuckle. In most broadcasting circles, the notion of laughing at a team or player is taboo. On Primetime, it was commonplace. It furthered the connection. Here was a man who graduated from Brown University, yet brought the conversational qualities of a friend at the bar.

“We were never personal, but if a team got beat 30-10 and shouldn’t have, what were they doing?” Berman said. “It wasn’t he stinks, they’ll never be any good, it was never to that degree. Today, that gets said and not backed up a bunch of times. We weren’t out to say somebody was horrible, but when the Bucs would lose again, we actually had fun when they won. That was a way to say ‘Look at this, the Bucs and the Creamsicles.’ We were just being honest, and a lot of it was because it wasn’t rehearsed.”

After years of highlights being read with the excitement of a DMV employee, Berman’s sayings and nicknames became instant hits. Although the show has been off-air for more than a decade, most viewers can note a half-dozen of their favorite nicknames.

“They just came,” Berman said. “You don’t think ‘I’ll be famous if I call Eric “Sleeping With” Bieniemy or Andre ‘Bad Moon’ Rison.’ A lot of them were under highlights which you can sing, like Steve “I got you babe” Bono. I had done them with baseball throughout the ’80s, so football was like fertile ground. They just appeared in my head sometimes. I didn’t look at rosters and try to make nicknames. Then you’re forcing it. It’s just like Primetime itself. It just worked.”

Andre Rison has the nickname tattooed on his right bicep.

Tom Jackson has a long resume. He played 14 seasons with the Denver Broncos, making three Pro Bowl and three All-Pro teams. He played in two Super Bowls, including Super Bowl XXI in January 1987, his final contest. That was almost the end of his story in the public eye.

Bornstein knew he wanted Berman from the jump, but adding an analyst required a search. Seven interviews were lined up. Of the group, Jackson went last.

“Oddly enough, I had never interviewed him as a player,” Berman said. “He played for Denver for 14 years and only his very last game in the Super Bowl, at media day, I was there, and I didn’t get to interview him. … I met him when he came in in April 1987. He was the last of seven to interview for the one former player/coach analyst job. I sat with all of them and I did a 20-minute mock. They sat with me and, of course, he had done a little TV in the offseason in Denver while he was a player. Not one year but several. … When you’re the seventh interview of seven, you never get it. Never. But he was so natural.”

Jackson was able to beat out Harvey Martin, Archie Manning and his former head coach Red Miller, among others.

A defining characteristic of Primetime was its ability to enlighten and educate. In this sphere, Jackson was a trailblazer. The former NFL star was the first to provide critical analysis to the sport in a studio setting, a place normally reserved for academics.

Jackson navigated the process and not just the result, something that created a generation of intellectually empowered fans who wanted more than a final score. Jackson’s intelligence forced networks and publishers to hire smart, with viewers developing an appetite for deeper discussion.

Throughout the first decade of Primetime, Jackson was the nation’s authoritative voice on all in-depth breakdowns. While Bob Trumpy and Dan Dierdorf provided analysis on national games, it was Jackson, and Jackson alone, who had the goods on every team, every week, in every household.

“He was one of the first players that to me didn’t just talk in the booth in clichés,” Banks said. “He really did try to peel back the curtain and show the average fan a little bit of how the game is actually played. They would use the video very intelligently to show where a coverage was blown or how a quarterback read a defense. They took you to a new level of understanding. Most people remember the shtick that worked for Berman but they forget how much the meat and real intelligence, nuts and bolts of the game, were provided by Tom Jackson.”

For his two decades on the program, Jackson’s mind was only equaled by his consistency. Sitting in a chair next to Berman on live television, Jackson had the innate ability to interject at the right time, understanding when a moment called for input or silence.

Perhaps the trickiest part was giving Berman the perfect counterweight for his bombastic style with an understated authoritativeness.

“It was a perfect mix because if Chris is more the over-the-top excitement, you couldn’t have paired him for so many years with someone of similar energy,” said Pidto. “Not to say Tom didn’t have energy, but it was a perfect mix in terms of even energy. He was always reliable and steady. There were a lot of times he made really, really great points on controversial subject matter. They were really close. They had a lot of chemistry over the years. As things have evolved, to think they aren’t doing this anymore is sad to me in a way.”

Berman’s style and Jackson’s analysis became staples of NFL Primetime throughout its run. Alone, each component added ample value, but they were tied together with a singular theme.

Primetime‘s music, produced by FirstCom, became a soundtrack to the league for millions. For many years, the same musical scores were played for the Raiders and Buccaneers, becoming synonymous with the teams. Others were reserved for the biggest dramas, the music lending itself to the narrative.

“That was our version of what NFL Films used to do with that music,” Berman said. “It wasn’t emulating but almost honoring them. I’m a music guy and I don’t know what all the music was called, but I know that was a big part for people and for us. While you’re doing the highlights, sometimes I would give it a beat and it would rev me up, subconsciously. … That was an ode to what preceded us.”

If there was any guideline for ESPN to follow, it may have come from This Week In Pro Football. The program ran as an hour-long highlights show from 1967-1975, hitting on every game in both the AFL and NFL. However, many couldn’t see Pat Summerall and Tom Brookshier due to the show running on the Hughes Sports Network. Even for those with access, the show tended to focus on a few key plays, with slow-motion replays and long cutaways used to fill the 60-minute block.

Until the rise of cable and, later, satellite television, sports remained relatively difficult to access in America. Most television executives believed the common fan only wanted to see his or her local team, a view that went largely unchallenged for decades. The birth of NFL Primetime exposed that to be a gross exaggeration, showcasing that football was king, regardless of geography. The ratings reflected this new reality.

“It’s the highest-rated sports studio show in the history of cable TV,” Berman stated. “We got in the fives and for a few years we averaged in the fours for the season. That won’t happen again. There weren’t 2,000 channels. In the ’90s and I mean late ’90s, we would get 5.3 in December for a show when the weather was crappy.”

While the popularity was driven by fans looking for an extra dollop of football before the work week began, it wasn’t limited to those who only watched. Quietly, the program was becoming appointment viewing for those within the game, from coaches to players.

Berman recalls one example that includes Don Shula, the NFL’s all-time winningest coach. At an owners meeting during his tenure with the Dolphins, Shula approached Berman to relay that Primetime was being used in Miami as a scouting tool. For teams in the NFC that the Dolphins didn’t typically see, Shula watched the highlights to glean what habits a team could be forming, and then game-plan against those throughout the season.

Bill Belichick didn’t watch Primetime for scouting but for family time, sitting down with his clan to relax during his time as the Giants defensive coordinator. It was a source of bonding for a man who became the only head coach with five Super Bowl rings.

“I watched it every week, unless I had a really bad game, then why torture myself and just go to bed,” said Phil Simms, current NFL on CBS analyst and two-time Super Bowl-champion quarterback of the New York Giants. “As an announcer when I started in TV, when I would get home I couldn’t wait to turn it on because it gave me a feel. The highlights were extensive and fairly true to the game itself. They didn’t trick up the highlights, the sequences were great. Of course, Tom Jackson being with Chris Berman, being an ex-player, always had a great take and nice overview of deception or the truth. I missed it when it went away. … Hell, it seems like only four teams are covered in the NFL.

” … It was a great show for fans, and it was a great show for players. I really wish there was a great highlights show to this day, I really do.”

My father and I still talk every NFL Sunday. It’s still over the phone, him in New York and me in Chicago. The distance is twice what it used to be, and yet it feels shorter thanks to modern technology.

We discuss a week’s worth of action in real time. It’s no sweat with NFL Sunday Ticket, a DirecTV creation that came to be in 1994 but exploded onto the mainstream scene in the 2000s. Usually, these conversations happen while NBC’s Football Night In America plays as background noise before Sunday Night Football kicks off. The program is fine, but it rings unnecessary. Nobody needs to see highlights that have been on Twitter and NFL RedZone all day long.

NBC acquired the rights to Sunday Night Football in 2006, effectively killing NFL Primetime on ESPN. The Peacock is permitted to air 60 minutes worth of highlights, something NBC Sports executive Dick Ebersol negotiated into the deal. Ebersol, a friend of Berman’s, made sure ESPN was not allowed the same highlights deal. It was a death sentence for Primetime.

Still, NBC doesn’t utilize most of its highlight allotment. Instead, it focuses mostly on short highlights followed by analysts talking and quick-hitters featuring Mike Florio of NBC-owner Pro Football Talk and Peter King of The MMQB.

NBC didn’t want to use the highlights. They wanted to make sure Berman and Jackson couldn’t.

Some insist the show had run its course. Pidto believes the internet’s rise was going to slow down Primetime sooner rather than later. In the eyes of some, it might have been time to draw the final curtain, allowing a transcendent program to go into the proverbial rafters. Others believe it could have lived on due to an increasing appetite for the NFL, along with its appeal to fans of all ages.

“The landscape hadn’t changed in ’05 or ’06, there was no RedZone,” Berman said. “It was a big screw-up on our part, although I don’t know we had a choice. I was not running out of gas, we ran out of the rights. It wasn’t down by any stretch of the imagination. The rating wasn’t a five anymore but the rating was still the highest we had on the network except for the game itself. I think there would always be a place for NFL Primetime. … I think it would be vital today. Not to the point in the ’90s maybe, but it would be sought out.”

To re-watch an episode of Primetime on YouTube is to go into a portal of NFL history. Berman, Jackson, the various co-hosts and the sets are outdated. Still, it’s an incredible watch. Highlights have never been broadcast in the same way before or since, both in style and substance.

In essence, Primetime was a victim of success. The show had grown a national appetite, and now it was being quenched by multiple outlets and avenues.

“It was a complete bonanza for the football fan to get everything in an hour,” Banks said. “It was a hugely important show for the growth of the NFL and for the behemoth it is today. It tied up the entire day.”

For those who watched, Primetime mirrors a first love. It can be replicated and imitated, but never duplicated.

Regardless of triumphs in studio or stadium, Berman and Jackson will forever be linked by a singular bond that was shared by legions of passionate football fans, enveloping them in a way impossible to ever experience again.

“That was the show,” Pidto said. “Seven to eight o’clock. To be on that stage, I can’t tell you what a thrill that was.”

In 2016, Jackson retired from television. The following year, Berman stepped away from his long-time role at ESPN after 38 years, now limiting his appearances. He’s received thousands of letters, many sharing memories and experiences of Primetime. I shared my story during our interview. It felt necessary. Berman didn’t need to hear it, but I needed to tell it. He needed to know what he, Jackson and Primetime meant to my family.

“It warms me to my heart, to this day, that we were a show for the football community,” Berman said. “That includes the fans, obviously, but the people within the game of football.

“It was tomorrow’s paper with pictures.”