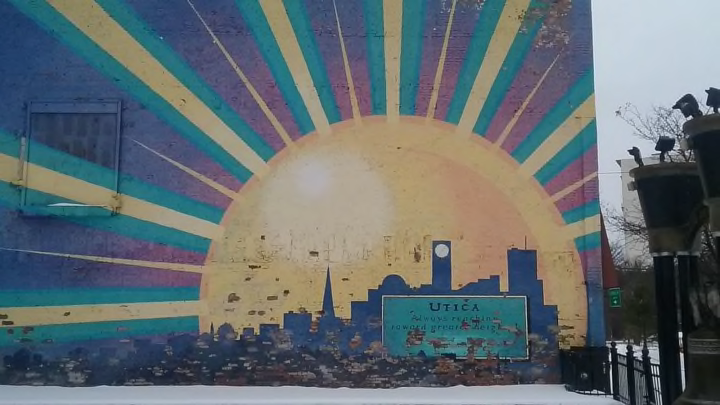

Basketball is a sanctuary in Utica, New York

By Ben Mehic

Ephraim Wright sunk free throw after free throw on the outdoor court at Hughes Elementary School, a small public school tucked away from meagerness of Utica, New York. Every time the ball swished through the hoop, Wright felt more frustration leave his body. It was a synergetic feeling for the 14-year-old, whose cousin, Laquan Wright, had just been shot while burglarizing a Virginia Beach home.

A helplessness brought Wright to the local court, and basketball, at the time, was the only thing that made him feel safe – just as it’s been for many of his peers who live in Utica.

“I was just shooting, shooting and shooting. I told myself, ‘I had to do something,’” Wright said.

With nearly 31 percent of Utica’s residents living below the poverty line – nearly four times the national average, according to the U.S. Census – basketball has become a well-trod route for youth struggling to to navigate through life in the decaying urban center.

Wright, now 21, found basketball when he was four and the sport hasn’t left him since. He played for John F. Kennedy Middle School, numerous local Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) teams – including the Utica City Rocks and D-Squad – and Proctor High School. His basketball career ended after high school but Wright, who now works a full-time job at a local bank in Utica, credits basketball with helping him through.

Originally, Wright wanted to try football, but for financial reasons, he decided to stick with basketball, which is the least expensive sport among the “big four” played in the United States, according to the National Council of Youth Sports.

“Football – it’s expensive. It didn’t keep my interest. Hockey and all the other sports, they cost a lot of money,” Wright said. “It costs money to buy skates and to get ice time. It costs money to golf, tennis and all that. For basketball, all you need is a court and some sneakers.”

Youth in Utica, where the median household income is $22,000 less than the national average, according to the Census, often turn to basketball to find an escape from the troubles that come with living in a struggling city.

Wright met his former teammate Jesse Pittman during a fourth and fifth grade scrimmage for Jones Elementary School. During the scrimmage, Pittman, a scrawny, pest-like guard, was tasked with guarding Wright, who was always the biggest kid in the classroom.

With a few dribbles up the court, Wright got by every help defender, forcing Pittman to face him at the rim. Pittman hacked Wright, but he finished through the contact.

“You little-a** punk,” Pittman remembers Wright saying to him while walking to the charity stripe.

Pittman, who grew up on Fairfax Place, had heard those words before, but for some reason, it felt different coming from Wright, who had gained respect from all the other kids on the court.

“We went at each other, even at that age,” Pittman said.

The animosity on the court caused the two to bond since it was the only place where they could be themselves, Wright said.

“There are certain things that you can’t do in school. I couldn’t act the way I wanted to act,” Wright said. “I was in fear of getting in trouble. But when you’re on the court, anything goes.”

Trouble is something that could be found on and off the court in Utica. The number of daily violent crimes in the city is one and a half more than the national average, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s 2015 Uniform Crime Report. Neither Wright nor Pittman went down that path, but have seen some of their childhood friends become victims of their environment.

“If you have trouble at home – if your mom is doing drugs and your dad isn’t home – that takes a toll on your life,” Wright said. “It builds up a lot of anger and basketball becomes a tool for you to express that anger. I leave the anger there. That’s my sanctuary.”

For coaches like James Peterson, the program director and head coach of the senior team for D-Squad, basketball has become a teaching tool for the youth. Peterson founded the AAU program in 1991, when it was known as the Utica All-Stars, as a way to give his sons an opportunity that he didn’t have growing up.

“We wanted to give them another alternative other than running the streets,” Peterson said. “We wanted to give them something positive and hopefully they take it from there.”

Peterson and coaches that lead lower grade AAU teams, like Wyatt Robinson, who coaches the eighth grade D-Squad team, preach the team’s mission – academics, scholastics and community – to ensure that the players are constantly reminded of the importance of maintaining a controllable life off the court.

“It teaches you to make the right decisions and helps you recognize timing,” Robinson said. “If you’re comfortable and confident, you’re going to be that way when you’re in school or at home. It helps you manage success.”

Robinson, who works two full-time jobs – one with the Department of Public Works in Utica and another as a program manager at Upstate Cerebral Palsy – hopes that his work ethic is one thing that his players learn from him. Robinson volunteers his time as a head coach for the program while managing his full schedule, which includes caring for his wife who suffered a ruptured cerebral aneurysm in the summer of 2015, causing her to lose 30 percent of her brain capacity.

He is a powerful role model, but still, he sometimes finds it difficult to get his message across to the players.

“It’s easier to get influenced with the wrong ideals,” Robinson said. “It’s more highlighted in a smaller city like Utica.”

A short trip from Utica to New Hartford – one that would take 13 minutes on an average day of traffic – shows the disparity between Utica and its neighboring towns. New Hartford’s median household income is $40,000 more than Utica’s and $18,000 more than the national household income, according to the Census.

Viewing that difference caused players like Wright to gain more motivation to “make it out” – even if they didn’t become professional basketball players.

“Seeing New Hartford, seeing how they lived, that makes a kid in the poverty areas hungry,” Wright said after having played the New Hartford Spartans during his time with the Proctor Raiders. “You do whatever you need to do to make it.”

Brianna Kiesel, a Utica native and Proctor graduate, is the only professional basketball player to come out of the city, having been drafted by the Tulsa Shock in the 2015 WNBA Draft. Kiesel, who was first introduced to the game when she was 3 years old at Addison Miller Park by her father, was noticeably different than the rest of the kids her age.

When she was 5 years old, Kiesel kicked a soccer ball from midfield and made a goal during a youth soccer game.

“We realized she was definitely something special,” said Nikki Hymes-Kiesel, Brianna’s mother.

Kiesel eventually decided to put all her attention onto basketball. She came up from middle school to play varsity as an eighth grader, but the size difference didn’t matter, according to her former coach Vinny Perrotta.

“She’s just a special kid,” Perrotta said. “I ask her, ‘Why are you different, Bri? Why don’t the kids understand what you understand?’ She’s just wise beyond her years. She sees the big picture and looked ahead to the future.”

Unlike some of her peers, Kiesel grew up in a two-parent household, which gave her some added stability and opportunity, Hymes-Kiesel said.

“We were confident she would be okay,” Hymes-Kiesel said. “When it happened, it was like ‘Wow, it’s really happening.’ Next day, she was gone,” said Hymes-Kiesel about the day her daughter was taken with the 13th overall pick. “She got an agent. My little girl was growing up, she was becoming a woman and getting better.”

Other players, like Josh Wright, Ephraim’s brother, had an opportunity to “make it out” with the sport, but failed to capitalize on the opportunities.

Josh Wright averaged more than 30 points per game during his senior season at Proctor in 2004, earning him New York State First Team honors and a scholarship to Syracuse University. Due to “academic troubles and personal reasons,” according to Orange Hoops, Josh Wright left the team after four seasons. Peterson coached the brothers for his AAU program and believes that Josh Wright would have benefited if he left the area, rather than accepting a scholarship at a school so close to home.

“I tell my athletes, if you can’t get away from the community, get away from your friends,” Peterson said.

Now, Josh Wright plays basketball for King of Kings, an unpaid, professional-amateur summer league in Utica that was co-founded by Donelius King and Brandon Long in 2006. Franklin Davis, who serves as the assistant director of the Utica City Rocks, which has developed a number of Division I athletes, believes Josh Wright could have made it to the NBA.

Peterson, who coached both Wright and Deandre Preaster, another Utica native who didn’t complete a four-year program after receiving interest from schools for both football and basketball, echoed Long’s belief that the city lacks afterschool programs.

“It’s a shame. When I first started, the Boys and Girls Club was open every day, even when kids didn’t have school,” Peterson said. “The program taught them life skills. Now the kids don’t have any of that.”

Long, a Spanish teacher at JFK Middle School, believes that the lack of after-school programs in the area has impacted the way kids develop.

“There needs to be more — definitely more,” Long said. “Obviously, money is always an issue, so that’s a big thing. There needs to be more, definitely.”