It took Ron Wolf 12 years to climb the front office ladder. Wolf went from an assistant with the Oakland Raiders to vice president of operations of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1976, then an expansion team preparing for its inaugural season.

Under Wolf’s stewardship, the Buccaneers lost their first 26 games, the longest such streak since the NFL-AFL merger and the subject of substantial ridicule. After three mostly frustrating seasons and an increasingly broken relationship with ownership, Wolf handed in his resignation, returning to the Raiders and Al Davis.

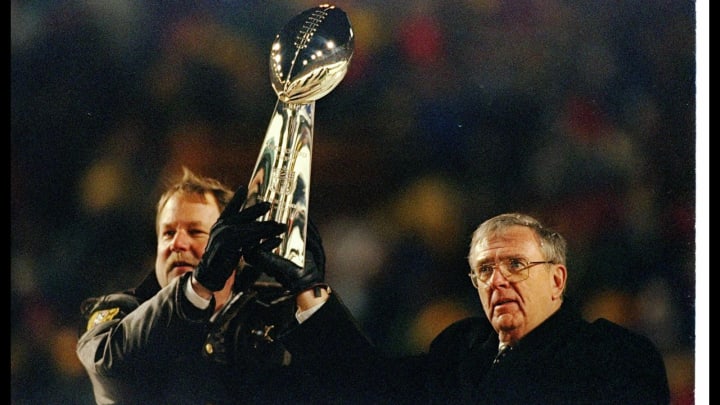

Wolf spent the next decade with the Raiders, largely hidden beneath Davis’ considerable shadow. During that time, he helped usher the franchise into its golden era, acquiring future Hall of Famers Marcus Allen and Howie Long in the draft as well as Pro Bowl talents such as linebacker Matt Millen and running back Bo Jackson. The Raiders brought home the Lombardi Trophy in 1980 and ’83, and further entrenched themselves as one of the league’s marquee franchises.

After enough time had passed since the debacle in Tampa, Wolf received another chance away from the Raiders. He joined the New York Jets as a personnel director in 1990, leaving in 1991 to become the Green Bay Packers’ general manager. Wolf’s time in Green Bay proved to be his defining period, restructuring the organization and positioning it for a nearly uninterrupted run of title contention that has lasted more than two decades.

Wolf’s achievements as a personnel executive landed him in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2015. During his speech, he discussed his multiple NFL stops, both successful and otherwise. That same year, longtime general manager Bill Polian earned induction for his time leading the Buffalo Bills, Carolina Panthers, and Indianapolis Colts. Polian too overcame numerous roadblocks during his career, including four consecutive Super Bowl losses in the early 1990s.

For Wolf and Polian, the opportunity to learn from earlier mistakes proved vital to their eventual success. The two combined for 10 Super Bowl appearances and four championships over the course of their careers, with each winning their rings after their terminations from the Buccaneers and Bills, respectively.

Yet, both Hall of Famers likely would have experienced wildly different career trajectories in today’s NFL, a league that has grown overly reticent to forgive early failures or hand over the keys to those with any significant black marks on their record.

The NFL has always lacked for patience, but the supply has further weakened over time. That mentality especially applies to those who run personnel departments, a group that includes general managers, head coaches, team presidents, and a host of other titles. Many of these executives and coaches, once empowered, receive little time to build a team in their image before ending up on the chopping block.

From 1980-99, 30 named or de facto GMs were either fired, made a subordinate, or otherwise departed after four years or fewer on the job. The amount mushroomed to 48 in the 18 seasons since, an alarming increase of 60 percent. That figure doesn’t account for interim general managers who never earned the full-time position. The numbers illustrate an unmistakable shift around the league: The pressure to win has accelerated the GM hiring cycle to the verge of terminal velocity.

Unsurprisingly, the Cleveland Browns headline the list of worst offenders. Since the franchise’s reboot in 1999, not one of its nine general managers has lasted more than four years. Two (George Konkis and Michael Lombardi) lasted a single season with the team before receiving their walking papers. Either as a consequence of the near-constant turnover or the catalyst behind it, the new Browns have reached the playoffs only once and, damningly, just completed the second 0-16 regular season in league history.

But misery loves company, and three AFC East teams reside in the Browns’ neighborhood. Between the Miami Dolphins, Bills, and Jets, 10 general managers have ceded power within four years on the job since the 2000 season. Not coincidentally, each of these franchises has lost most of their games over that span, with the three combining for a winning percentage of just .457.

Undoubtedly, these struggles have benefited the division-rival New England Patriots, who won the AFC East 15 times since 2000 while establishing a modern dynasty.

No single factor can account for the rise in early GM terminations, but changes in player acquisition and the NFL’s player-compensation system have likely played a role.

“The biggest change in the game from the ’80s to now is free agency and the salary cap,” longtime general manager Charley Casserly, now an analyst for NFL Network, explains. “It gave you a quicker window to win. It gave you less of a chance to keep a team together. The money skyrocketed, so you’re going to make some decisions that might be riskier because of the money and feeling the need to win. I think that probably has attributed to changing general managers faster now than before.”

The shortened contention window has made parity the order of the day in the NFL and changed the way fans and media view the game. Just as importantly, it has affected what team ownership expects from their top executives, especially owners that have come into the league more recently.

“I think that because you could have less player movement, there had to be more patience before and therefore owners learned patience,” Casserly says. “Now, I don’t know if owners have as much patience as they come into the league and understand that there’s a process you have to go through. Before, everyone knew it because they had to know it. There was only one way to build a team, and that was over time.”

Though more speculative, the evolution of the media landscape might have also pushed ownership to fire general managers sooner than in past eras.

“The growth of the media has skyrocketed,” Casserly says. “Social media has added to this. In other words, now there are more voices out there than there were before. Do owners react to that more than they did before? I don’t know. That’s just a theory.”

Disposing of general managers so quickly creates manifold problems for the franchises involved. Front offices under the gun tend to favor win-now decisions such as lavish free-agent spending or passing over a talented draft prospect for a lesser player at a position of need. Such decisions might preserve a general manager’s job, but they typically don’t bring a team closer to winning a championship.

Perhaps no club has committed more of these mistakes in recent times than Washington. Since 2000, the team inked some of the biggest free-agent busts in league history, a list headlined by Jeff George (signed four-year deal, made seven starts), Adam Archuleta (six-year deal, seven starts), and Albert Haynesworth (seven-year deal, 12 starts).

During the same stretch, the franchise invested a combined five first-round picks in quarterbacks Patrick Ramsey, Jason Campbell, and Robert Griffin III. None lasted more than four seasons with the team. In attempting to speed up the team-building process, Washington ended up falling well short of title contention, reaching the playoffs just four times in the last 18 seasons and never advancing further than the Divisional round.

“There’s a value to patience and understanding why a team hits a lull, why the team is losing,” Casserly says. “They don’t have good players, and that’s where ownership and the general manager have to understand that patience is needed.”

But the league’s GM problem goes beyond a quick firing trigger. Only 10 executives and coaches tabbed to run their first personnel department since the start of 2000 have received a second such opportunity. By comparison, at least 22 first-time general managers hired between 1980-99 earned a second chance in the big chair. Now more than ever, the NFL doesn’t forgive failed tenures.

And that reduction since 2000 becomes even more concerning when considering the context. Three of those 10 named or de facto general managers (Andy Reid, Scot McCloughan, and John Dorsey) emerged from a Packers organization uncommonly gifted at producing talent evaluators, an anomaly within the league. Two others (Howie Roseman and Marty Hurney) received their second GM opportunities with the team that gave them their first. Yet another (Ruston Webster) ran his first front office on an interim basis only.

As teams continue to discard general managers after a single use, the demographics of the league’s general managers will undergo a problematic change as a result.

“You’re going to be hiring less-experienced coaches and less-experienced personnel men,” Casserly says.

If so, reclamation stories in the vein of Wolf and Polian appear increasingly unlikely to unfold in the future.

Despite the negative outlook for modern NFL general managers, their plight doesn’t necessarily have to continue in this manner. Newer ownerships in other sports, such as the NBA’s Jacob Lacob, have taken a progressive approach to their team operations that offers more latitude to their top executives and coaches. Lacob and his group of investors purchased the Golden State Warriors in 2010 and displayed remarkable patience as the team slowly developed from a 26-win afterthought into a record-setting, two-time champion.

Perhaps someone with a similar mindset will eventually acquire an NFL franchise and achieve success, prompting others in a famously copycat league to follow suit.

Still, even if teams recognize the problem, the factors that have made GM jobs more tenuous than ever don’t seem likely to change in the foreseeable future. The pressure to win will only further erode patience from ownership, and the heightened public scrutiny will accompany any general manager who failed with a previous team.

All of which suggests that, absent a profound paradigm shift, the NFL’s GM crisis will continue in the decades to come, and that could mean the league misses out on some great team builders.

“There are too many people getting fired in too short of tenures,” Casserly laments. “Tom Landry didn’t have a winning season until his seventh year. Tom Landry wouldn’t have lasted seven years where we are today.”