Dressed in pink and full of confidence, Justise Winslow called his own number.

He dribbled past half court and signaled for a play. A few feet in front of him was Kawhi Leonard, perhaps the league’s best perimeter defender since Scottie Pippen. Winslow’s teammate Rodney McGruder came up to screen Leonard but scattered away at the last second without making contact. Winslow didn’t need the help. He bolted left toward the baseline with a staggering first step that seemed to catch Leonard by surprise. Suddenly Winslow was a running back, hitting the thrusters to get to the edge and blowing past the defense. Winslow finished with a two-handed slam and stared down the Toronto Raptors bench as the Heat took a 15-point lead in a late-December game against one of the East’s best.

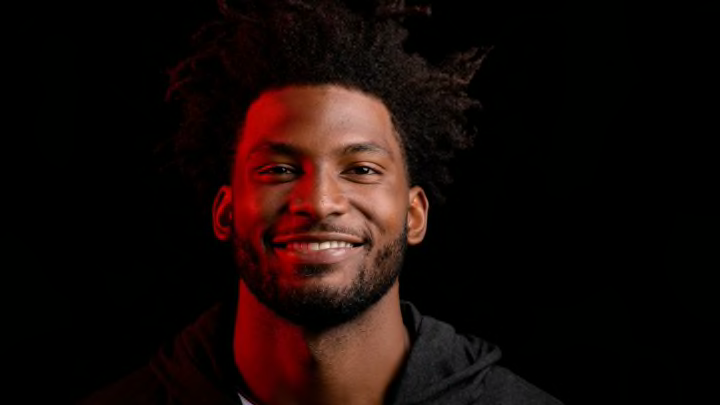

Justise Winslow, the Heat’s new starting point guard, has turned a corner.

https://twitter.com/MiamiHEAT/status/1078108066414030848

When Goran Dragic was shelved midway through December after undergoing a procedure on his knee, Winslow stepped in to run the point full-time. He had been the Heat’s de facto point guard off the bench for most of this season and last, and after Dragic went down he was tasked with leading what had been, at the time, a bottom-five offense. With more responsibility came great power.

“I like being in charge, to be honest,” Winslow told The Step Back after a recent home win over Milwaukee. “I like the responsibility. If we lose, I’m going to take full responsibility for that and, if we win, I’m probably going to take none. That’s the beauty of playing point guard, and that’s what you want in any role in life. You want more responsibility.”

Winslow was the hottest thing in Miami in December, averaging 14.8 points, 5.6 rebounds and 4.0 assists while shooting 47.5 percent and 41 percent on 3-pointers. Miami’s offense rose from 25th in offensive rating to 15th during that stretch as the Heat won six of their final eight games of the month and secured pole position for a playoff seed in the East. If you’re looking for a turning point of the Heat’s season, this was it, and it may also have been the leap that Winslow had been working toward for years.

There were hints of a leap forthcoming in last season’s first-round playoff exit to the Philadelphia 76ers. The Heat won just a single game out of five and were thoroughly out-talented by a young Sixers squad, but Winslow’s performance was a silver lining. He went toe-to-toe with Ben Simmons on defense, shot well from the perimeter (36.8 percent on 3.8 3-point attempts per game) and, in Game 3, recorded a double-double with 19 points and 10 rebounds and infamously stepped on Joel Embiid’s goggles. Yes, it was an act of poor sportsmanship, but it was also a lightbulb moment in which Winslow found his swagger.

Now in his fourth season, Winslow is building on that playoff performance (he’s had a knack for stepping up in the postseason, memorably playing center in a second-round series against Toronto as a rookie). The Heat’s roster has been disappointingly consistent over the last three seasons, but the power structure has flipped. Miami’s best players are no longer its veterans, as Winslow, Josh Richardson, Bam Adebayo and Derrick Jones Jr. force their way into more playing time.

Winslow is on track to become the Heat’s best player by the end of the season. For the former No. 10 overall pick who faced doubts and was labeled by some as “Bustise” after an up-and-down start to his career, his recent leap has been remarkable. But how did we get here?

IT STARTS IN HOUSTON

Justise is the son of former NBA player Rickie Winslow. Rickie played for the University of Houston in the 80s, where he was part of the Phi Slama Jama squad along with Hakeem Olajuwan and Clyde Drexler, and was later drafted by the Chicago Bulls. However, Rickie’s career failed to take hold in the NBA, and after one season he went overseas to embark on a successful career in Europe before eventually returning to Houston and taking an assistant coaching job at St. John’s School.

Growing up in Houston, Justise participated in the AAU circuit and played basketball at St. John’s along with his older brother, Josh. St. John’s head basketball coach Harold Baber said that there was a buzz about Justise as early as sixth grade. Justise grew three-to-four inches between seventh and eighth grade and, as a gangly ninth grader, he was starting as the varsity team’s best player.

“To see him in practice you could just tell that he was a special-type player and a special-type talent,” Baber said.

Justise competed for a championship in each of his four years, winning three times. His calling card was his versatility. In AAU he played the 3, and at St. John’s he played 1 through 5. Justise was comfortable guarding point guards and centers and everything in between. Baber had him guard current Indiana Pacers center Myles Turner when their high school teams met.

Justise’s tweening size also made him a tough matchup on the offensive end.

“Sometimes it was point, and if he had a smaller guy he would take him in the post. A bigger guy, he would take him on the perimeter. I think that’s what helped the evolution of his game and him being so court savvy, because he did have the ball in his hands a lot in different spots on the court,” Baber said. “Not just a typical point guard but down on the block, high post, short corner you name it, we were finding ways to try to get him the ball in different areas.”

At first, Baber said, it was a challenge to figure out where to play his standout freshman forward. Justise thrived in the middle of the court, the area usually occupied by the point guard. So Baber decided to put the ball in Justise’s hands and let him decide. “He was just really good at taking advantage of whatever situation that game called for.”

Justise averaged 15.3 points, 9.6 rebounds, 3.2 assists, 2.6 steals and 2.2 blocks per game as a freshman, and led St. John’s to its first state championship in more than 30 years. In the championship game versus Bellaire Episcopal, St. John’s trailed by as much as 17-3 in first half but cut the lead to single digits after halftime.

Down by one point with 10 seconds remaining, Baber called a timeout and drew up a play putting the ball in Justise’s hands. He brought the ball out and let a few seconds tick to make sure St. John’s would end up with the final shot before attacking. As he drove to the basket, the defense collapsed on him. “He could have forced up a shot and nobody would have been mad,” Baber said. Instead, Justise found his brother, Josh, cutting to the basket and dumped it off to him. Josh laid it up at the buzzer. A game-winning shot for him, a game-winning assist by Justise.

“The guy could have averaged 40 or 50 points a game in high school,” Baber said. “Would we have won three championships in four years? Probably not. He could have easily put up the numbers, but he trusted his teammates. He had a knack for knowing when to take over, when to get guys involved. It was just one of those uncanny things that you really don’t teach.”

By Justise’s junior year, the college letters and scouts started coming in a steady stream. Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski would show up for practices at 6 in the morning to get a look, later saying he reminded him of former Blue Devil Grant Hill.

After winning his third state championship as a senior, Justise went off to college, where he played a major role in Duke’s championship run in 2015. In 39 games as a freshman, he averaged 12.6 points, 6.5 rebounds and 2.1 assists as a power forward. He didn’t have the ball in his hands as much as when he was in high school, but he filled a need and won his fourth championship in five years. After one collegiate season, Justise declared for the NBA Draft and was selected by the Heat with the 10th pick.

A TURBULENT START IN MIAMI

After a disappointing season following the departure of LeBron James, the Heat were surprised when Winslow was still there at No. 10. During the draft process, Winslow had been compared to all-pro forwards like Leonard and Jimmy Butler, but Pat Riley had a different player in mind when the Heat selected him.

“Justise can guard four positions. I think you saw something in the Finals this year that was a little different when you had a 6-foot-7 forward [Draymond Green] playing center. Justise is similar to Draymond Green,” Riley told reporters after the draft.

And so the endless high-ceiling comparisons persisted. They weren’t just reference points manufactured by the media. Winslow privately compared himself to those same players. He looked at Leonard and Butler in particular as guys who overcame below-average jumpers to become elite scorers. Over the last couple of years in the NBA he’d get frustrated when he wasn’t scoring like he wanted to.

Dating back to high school, Winslow struggled with his perimeter jumper, and he was entering the NBA at a time when there was perhaps no more important skill. At Duke, he made 41 percent of his 110 3-point attempts, but there were still questions about his NBA range. As a rookie, Winslow converted just 27.6 percent on 116 3-point attempts and struggled to make shots outside of 10 feet from the basket. He had a bad hitch in his stroke and his form was inconsistent.

After Winslow’s rookie season, Heat head coach Erik Spoelstra hired shooting coach Rob Fodor to work with the team. But before Winslow could see the fruits of his labor, his second year was cut short by surgery to address a right shoulder injury, after just 18 games.

He returned at the start of the 2017-18 season, but his third year didn’t do much to satisfy the expectations that came with being a lottery pick. Winslow averaged just 7.8 points, 5.4 rebounds and 2.2 assists while shooting 42 percent. He did manage to make 38 percent of his 3s, but it was on just 1.9 attempts per game, and some wondered if it was a repeat of his small-sample season at Duke.

Not helping ease any frustrations was the fact that Spoelstra struggled to find a regular role for him. Winslow played everywhere between an oversized backup point guard to an undersized starting power forward. He see-sawed between guarding opposing bigs and guards and, among the defensive upheaval, never found his rhythm on offense, not once scoring more than 18 points in 68 regular-season games in his third season. The versatility was a blessing and a curse.

However, Winslow stepped up in the playoffs against the Sixers and, after reportedly dangling him in a potential Jimmy Butler trade over the summer, the Heat signed him to a three-year extension before the start of the 2018-19 season. The investment already seems to be paying off. Spoelstra has settled on playing him at point guard and Winslow spread last season’s shooting percentage over more attempts.

“[Defenses] are starting to put a hand up,” Winslow said. “I’m definitely confident in whatever 3-point shot it is and I’m just finally feeling really comfortable out there, and I think it’s showing.”

Winslow’s usage has climbed past 20 percent for the first time in his career and his confidence is surging. It’s not uncommon to see him snake a pick-and-roll, pull up from mid-range or try a new finishing move at the rim. Glares and scowls are habitual gestures. For the first time since high school, he’s playing the role he’s most comfortable in.

“Growing up, especially on my high school team, I had to do it all. I had to be the point guard, the center, the wing, I had to do all of it. I think that’s where my versatility started,” Winslow said. “And with guys in and out of the rotation and my leadership vocally and my ability to see things and read things with my IQ on the floor, it kind of just happened naturally.

Last year it was ‘point forward’ and, now that I’m making 3s, they dropped the forward and put the guard at the end.”

Winslow says he gets energy from having the ball in his hands, something that translates from facilitating and shooting to his defense. Not only has #PointJustise elevated the Heat’s offense, but also the Heat’s defense. With Winslow on the court, Miami has a defensive rating of 100.5 versus 107.2 with Winslow on the bench–the biggest swing of any Heat player.

“He’s putting together some rock-solid floor games and really inspiring on both ends of the court,” Spoelstra said after Winslow finished with 24 points, 11 rebounds and seven assists in a win over Cleveland. “But really only people notice or look at that final number on the box score. I don’t want that to define the impact that he’s making–how many points he’s scoring. It’s about being a complete basketball player for us on both ends, and he did that tonight.”

FUTURE OF THE FRANCHISE

When Dwyane Wade retires at the end of the season, so too will the greatest player in Heat history and the only star on the roster. Wade hasn’t been the Heat’s best player this season but, after the league’s first returns, he has the second-most All-Star votes among guards in the Eastern Conference. That’s star power, and it’s important for marketing and team building.

The Heat are looking for a face to take over the franchise, and Winslow’s recent leap makes him a prime candidate. When asked about Winslow’s play, Wade joked “I feel like I can retire now.”

“He’s playing well. It’s not by mistake at all. He definitely put the work in,” Wade said. “I think earlier in the season, he was a little frustrated because it didn’t come as quick as he wanted it, but we just kept staying on it. I stayed on him and he stayed on his work, and you can tell the game is now slowing down for him. Once the game slows down for you it’s scary how good you can be.”

Despite entering the league at the worst time for a non-shooter, Winslow’s work has put him in great position as the league evolves. Players like Winslow — point forwards — are taking over offenses in Philadelphia, Milwaukee and Dallas while Duke wunderkind Zion Williamson projects to do the same. Winslow is in that group.

“Having a guy with size handling the ball definitely helps. I think a big thing the NBA is trending towards is just having your best player handling the ball,” Winslow said. “I’m not saying I’m the best player, but you see James Harden in his MVP year, Russell Westbrook, LeBron, you know, just having your best playmaker handling the ball.

I think for a lot of us, Ben Simmons-types, I think there is a lot of guys who are big guards and they can make plays.”

Maybe those early comparisons weren’t so far off, after all.