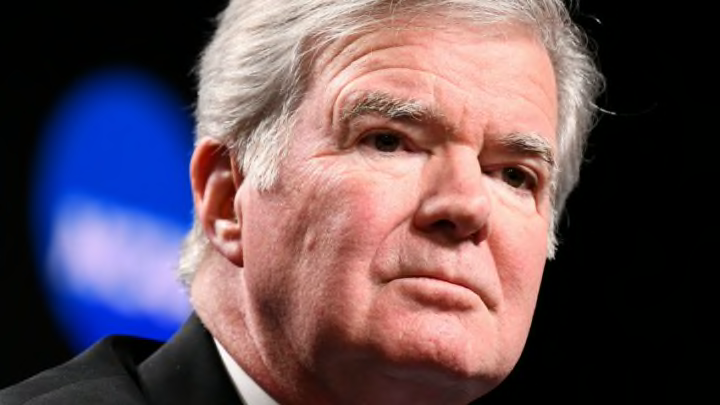

In his latest remarks, NCAA President Mark Emmert continues to show little or no respect for the student-athletes he oversees.

It has been 25 years since actor Bob Gunton brought a sublime level of evil and abuse to the character of Warden Norton in The Shawshank Redemption. That begs the question of whether someone should do a reboot of the classic.

If that happens, perhaps NCAA President Mark Emmert should be cast as Norton. He pretty much has the character down pat.

The latest example is Emmert’s comments this week about whether college athletes should be able to control their likeness as a solution to the issue of them getting paid. This should be a no-brainer by now. The NCAA has already lost twice in the courts (see the Ed O’Bannon case) on this matter. Mark Walker, the Representative from the basketball-loving state of North Carolina, said in March, “Signing on with a university, if you’re a student-athlete, should not be (a) moratorium on your rights as an individual.”

A college scholarship is a great and valuable thing. For 98 percent of college athletes, it’s a wonderful deal, a chance to earn roughly $30,000 to $60,000 a year in annual benefit for an opportunity to get an education. The system isn’t perfect, but the deal is a good one.

But it shouldn’t be a contract that takes away all the rights of an athlete to make money off his name, his signature and any other part of his likeness. That’s the deal that colleges have been leveraging against players for decades, hiding behind absurd arguments about amateurism and fearful of boosters getting out of control.

That’s at the root of Emmert’s comments this week in advance of the Final Four.

“We’ve talked to the congressman and tried to understand his position,” Emmert said. “There is very likely to be in the coming months even more discussion about the whole notion of name, image and likeness [and] how it fits into the current legal framework. Similarly, there needs to be a lot of conversation about how, if it was possible, how it would be practical. Is there a way to make that work? Nobody has been able up with a resolution of that yet.”

That’s pure and utter BS. It’s like Norton talking about his prison works program and then taking bribes on the side. What is there to understand about Walker’s position? The courts and anyone with common sense have already said that athletes should control their rights. There’s nothing more to discuss.

As for how it would work out from a practical standpoint, that’s easy to figure out. Yes, some rich guy who owns a car dealership in Alabama is going to offer some hotshot player a big endorsement deal to play for the Crimson Tide. That scenario is going to play out across the country. It will be perceived as unfair.

Here’s the deal: It already happens. It just happens behind closed doors and in nefarious ways, which is a great learning tool for young athletes with the promise of making millions in the future (just so you know, that’s supposed to be read in a sarcastic tone). If an athlete controlled his likeness, he’d be able to make money in legitimate ways and maybe even learn things about banking and finance. You know, things that are useful to future success.

Instead, the NCAA and its member colleges continue to worry about who controls the revenue streams, ignoring the fact that they already make obscene amounts. The fact that college coaches are making upwards of $8 or $9 million a year while players can’t make $10 from an autograph is a grotesque perversion of how this should work.

Of course, the unintended consequence of that is athletes and the general public don’t trust colleges to do the right thing. To carry the opening comparison to its natural extension, if Emmert is Norton, the colleges are guard Byron Hadley.

In fact, it’s worse.

What the NCAA and its member colleges do by controlling the likeness of athletes is even more reprehensible because the NCAA and colleges should know better. They should also be the ones teaching a higher ethical standard and leading athletes down a path of enlightenment and enrichment. One of the constant refrains about professional athletes in the NFL and NBA is about how so many of them go broke after they’re done playing. The NFL and the NBA take a lot of heat from the general public about why that happens.

Yet few people tend to point out that almost all of those athletes also went to college, evidently learning very little about finance from the very institutions best suited to teach them. In fact, colleges do their best to leverage the NFL and the NBA into making sure the best players stay in college as long as they can. It is intellectually corrupt and obscene.

It is, to borrow a word from Andy Dufresne, obtuse.