WWE’s big announcement follows a long history of pro wrestling going back to what works. But it rarely goes the way it’s planned.

House show attendance was down. Ratings had fallen. Locker room morale was low. After a meeting with the network, it was decided that a change of direction was needed. The man brought in to right the ship had a long track record as a creative force behind the highest-rated show in cable television, who outdrew the juggernaut World Wrestling Federation at the box office. People were excited. Hope was restored. But six months later, it was all over.

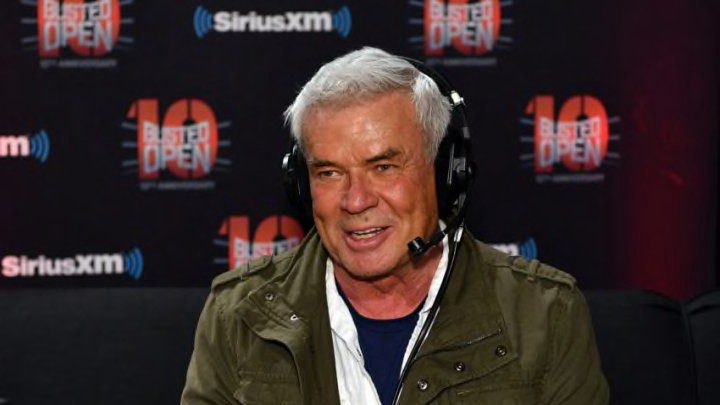

If Thursday’s WWE announcement of the hiring of Eric Bischoff and Paul Heyman as “executive directors” of SmackDown Live and Monday Night Raw, respectively, seems a bit familiar, it’s because we’re currently re-living one of pro wrestling most popular tropes: Hiring a booker/writer/executive based on their success in a previous era. Thursday’s announcement was eerily similar to the situation Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling found itself in the summer of 1992.

When Turner Broadcasting bought Jim Crockett Productions in 1988, they thought they were saving the company from financial collapse. But after four years of poor box office at the ticket window and on pay-per-view under Jim Herd and Kip Allen Frye, a change was needed. Turner officials seemed to listen to the newsletter community when they hired Bill Watts.

Watts was a main-event talent who bought half of the old Tri-State Wrestling territory in 1979, and with booker Ernie Ladd, immediately made a huge impact. Watts’ greatest stroke of genius was remaking a mid-card Calgary heel, Big Daddy Ritter, into the Junkyard Dog. The Dog became the biggest draw in the territory with many sellouts in New Orleans. Under Watts’ leadership, Mid-South Wrestling became one of the hottest territories in the country.

When Vince McMahon’s WWF made its initial expansion, Watts was ready, outdrawing the WWF every time they came to into the Mid-South territory. In 1985, the Mid-South program on TBS was the highest-rated show in all of cable television, even without the JYD, who’d jumped to the WWF.

Re-christened the UWF in 1986 and with a list of top-notch talent, Watts was ready to join the push toward national expansion. But Watts couldn’t fight the sagging economy in Oklahoma, the territory’s base of operations. Seeing the writing on the wall, Watts sold the UWF to Crockett in 1987, who promptly killed the promotion to prove that his promotion was “better.” That should also sound familiar to long-time fans.

When WCW brought Watts back, fans and wrestlers alike expected it to be the UWF, reborn. Instead, they quickly discovered that the business passed Watts by in the six years he’d been away. Instead of pushing Sting as the top face, Watts tried to recapture the success of the Junkyard Dog with Ron Simmons.

He also made jumping off the top rope illegal, killing the action of high-flying babyfaces like Brian Pillman and Justin Liger, on top of removing the ringside mats. Watts’ backstage policies were just as archaic, creating a system of fines that made the locker room an even more miserable place. Eventually, Watts was removed after a racist tirade in an interview with Pro Wrestling Torch’s Wade Keller. Watts’ replacement was Eric Bischoff.

Bischoff, like Watts before him, was able to challenge the WWE thanks to the success of the nWo angle. But like Watts, Bischoff had difficulty letting go of his greatest creation. Bischoff milked the nWo until it was a ghost of itself, in the same way Watts time and again failed to recreate the Junkyard Dog with the likes Master Gee, The Snowman and Iceman King Parsons.

And much like the five-year break Watts had between his UWF and WCW tenures, it’s been six years since Bischoff was actively involved with a wrestling promotion. His most significant contribution to TNA, Aces and Eights, was basically the nWo-meets-Sons of Anarchy. Both men also pushed their sons well before they were ready for the spotlight.

The general consensus seems mostly positive for the creative shift. WWE ratings and house show revenue are down, and the company desperately needs a spike of creativity. While Heyman and Bischoff have track records, their major successes were decades ago, and one can’t help but wonder if they can deliver something new or will just go back to what they know works. The one variable in this is McMahon himself.

For McMahon, control over his product is central. Only once in the history of his company did McMahon willingly give up a degree of creative control. In the fall of 1995, McMahon hired none other than Watts to head creative. It lasted three weeks.

To quote writer J.M. Barrie, “All of this has happened before, and it will all happen again.”