John Stockton’s short shorts were not with the times, but much like Stockton’s career itself, their length never wavered throughout the 1990s.

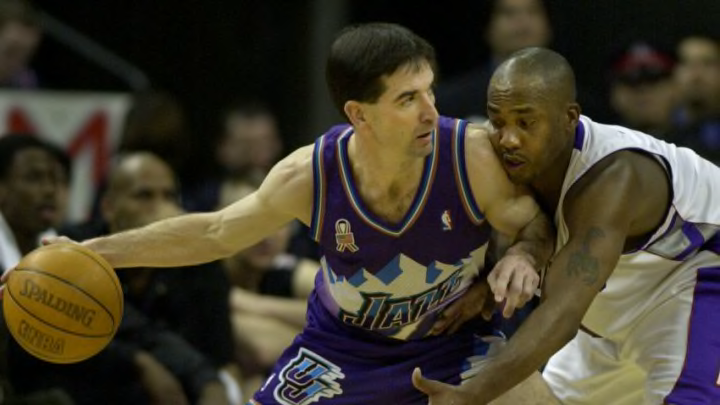

I attended elementary school in the early to mid-1990s, and I still remember being made fun of for a pair of jean shorts that, despite touching the top of my knee caps, was not considered long enough. A kid named William, who wore the flyest clothes in the entire fifth grade, called them “knee cutters.” John Stockton did not have to brave the playgrounds of Athens, Georgia, but he did wear short shorts on national television as a member of the Utah Jazz. His shorts did not cut the knee. His shorts hung 3-5 inches above the knee and did so for the entirety of his 19-year career.

John Stockton was not trending with the times. As he grew long in the basketball tooth, his shorts appeared to do the opposite. As Ridgemont High gave way to Bayside and West Beverly High Schools, the clothes grew ever more expansive. Hangin’ with Mr. Cooper meant owning a bigger wardrobe, and by the end of the decade, even the Indiana kids at Deering High School would be wearing baggy shorts.

Throughout the 1990s, the Utah Jazz inched their way up the Western Conference playoff ladder and toward the NBA Finals. In 1997, they would finally arrive in the basketball promised land, and they would repeat the feat the following year, losing both appearances to the Chicago Bulls. Those two series are filled with indelible images. Michael Jordan, after all, owned the decade by winning six titles in dramatic fashion, and in large part that was because of how Utah pushed him and his team to their limits. Stricken with the flu, he had to lean on Scottie Pippen. Doubled by Stockton, he had to dish to an open Steve Kerr. Shoved to the brink, he had to shove Bryon Russell.

Throughout those championship series, a less iconic visual also occurred every time either Utah’s Hall of Fame point guard or Chicago’s Steve Kerr guarded each other. While Stockton was listed as two inches shorter than Kerr, his shorts were probably 3-4 inches shorter than those belonging to the 3-point specialist and future head coach of the Golden State Warriors. Kerr was always one of the league’s corniest personalities, but even he knew the boundaries of fashion, that dressing like all you needed were some tasty waves was no longer cool, even if buzzed. (Note: John Stockton, a devout Catholic playing ball in the heart of Mormon Salt Lake City, was most likely never buzzed.)

So Stockton’s appearance in anachronistic basketball gear, whether a result of his own agency or an acceptance of whatever the higher-ups might stash in his locker on game days, seemingly worked against hegemony. He was the residual culture in the game, not to mention Utah as a historical territory was always an exodus away from the state of Illinois. Just as Michael Jordan racked up seven consecutive scoring titles, Stockton piled up nine consecutive years in which he led the league in assists.

The drums begin the song, a street whistle shrills, and then the voice sings, “Sometimes I dream that he is me.” Michael Jordan wasn’t simply the league’s most recognizable face; he was its spiritual façade. Hardware and endorsements confirmed this visual as substance. He also changed how the league dressed on and off the court. The suits and the uniforms both grew bigger to cloak the size of Jordan’s persona. And, on the court, His Airness is believed to have worn his light blue college basketball shorts from the University of North Carolina underneath his red and black Chicago Bulls uniform. Difficult to imagine is Stockton wearing anything at all underneath his Utah Jazz shorts.

Perhaps Jordan’s superstitious layering of the wardrobe is a practical reason for his wanting to wear a baggier outer garment. Perhaps he was hiding a dependence on light blue Horcruxes. Stockton, on the other hand, played as a man with nothing to hide.

Whenever asked about his shorts’ refusal to get with the times, Stockton gave no particular reason. His choice is an example of lower-case conservatism. He played his entire career in the same colloquial manner in the same cute city. He did what was comfortable because it was comfortable. Nothing ever changed, from his haircut to the cadence of his dribble against the hardwood to the length of his shorts.

Many men are like this. They believe responding to trends is a sign of fragility. They question the alternatives to their own lifestyle choices. They may even challenge those choices. They do not, in other words, want to be like Mike.

Maybe Stockton never felt this defensiveness that so often gives way to hostility. Maybe he was so busy feeding Karl Malone in the post that he saw nothing else in the world around him. Maybe doubling Mike simply made basketball sense, and yet Stockton wasn’t just a man in short shorts. He was a cult of personality without much cultivating.

As the league’s fashion changed so did its demographics. The league Stockton retired from was less white than the league Stockton had entered. He probably didn’t think much about this. He probably just thought about basketball and, specifically, feeding Karl Malone in the post, but nothing made John Stockton appear whiter than those short shorts exposing the paleness of his inner thighs, especially as the man pounced into a traditional defensive stance and aimed to pick metaphorical pockets. He probably didn’t notice, but others did, primarily the descendants of those seeking an isolated freedom in Utah noticed. While Stockton probably just felt comfortable playing in shorts as snug fitting as an undergarment, his comfort became a talisman for embodying certain ideals and values on the basketball court that were beyond his control.

Michael Jordan played for Dean Smith, which means he imbibed all those lessons about playing the right way too (even if playing in such a way sometimes reined in his unique talents), but Stockton became the white personification of an earlier era’s mythology, especially as Allen Iverson crossed up Jordan to close out a decade, especially as that same cornrowed point guard named Iverson stretched the game’s shorts ever longer and longer, especially as a full name was shortened to just two letters, A.I.

Stockton’s last year in the NBA was the 2002-03 season. He was a 40-year-old in a young man’s league. He was always a 40-year-old in a young man’s league. He averaged 10.8 points per game that season and 7.7 assists — not his best, but also not bad given the mileage on those hairy dad legs.

The next NBA season — and the first in two decades without the point guard from Gonzaga who would never be known as just J.S. — would witness an explosion of violence between the league’s fans and its players. The event that became known as the Malice at the Palace would raise questions about the boundaries between fans and athletes, violence and self-defense, tough guy and thug, white and black, that resemble similar questions often asked by or to zoning commissions, city planners and the justice system.

The league would respond with a dress code for all its teams and all its players, and believing it had an image problem in the eyes of its white fans, the league aimed to restore comfort for those fans. What the league did not do, however, even as it demanded a professional norming of its players’ wardrobes, was ask for players to wear Stockton-esque shorts again, for no one other than John Stockton could ever be comfortable again while playing the great sport of basketball in those out of fashion hotpants.

That stich had sailed, and to see it, one would have to, in the words of my fifth-grade classmate, look for the point guard with the daisy dukes on. Pardon the pun, but you can probably even call it being short-sighted.