Larry Walker making the Hall of Fame shatters the Coors Field stigma, which could lead to Todd Helton and other Colorado Rockies getting in behind him.

Larry Walker didn’t grow up chasing dreams of big-league grandeur. Instead, as a kid in Maple Ridge, British Columbia, he was chasing pucks around the rink as a hockey player. Now he’s the second Canadian player to make the Hall of Fame, joining Ferguson Jenkins.

His story is unique among Baseball Hall of Famers, a group he now belongs to after being elected to Cooperstown on Tuesday along with Derek Jeter (Ted Simmons and former MLBPA executive Marvin Miller were elected in December) in his 10th and final year of eligibility. He wasn’t a top prospect; never drafted, he was signed as a free agent by the Montreal Expos in 1984 for $1,500.

Raw wouldn’t even begin to describe his baseball abilities in his first foray into professional baseball. He didn’t play high school baseball because his school didn’t field a team. He estimates he played 10, 15 at most, baseball games a year before turning pro. In his first stint in the minor leagues, with Utica in the New York-Penn League, he once tried to tag up at first base by cutting across the pitching mound, skipping second base altogether.

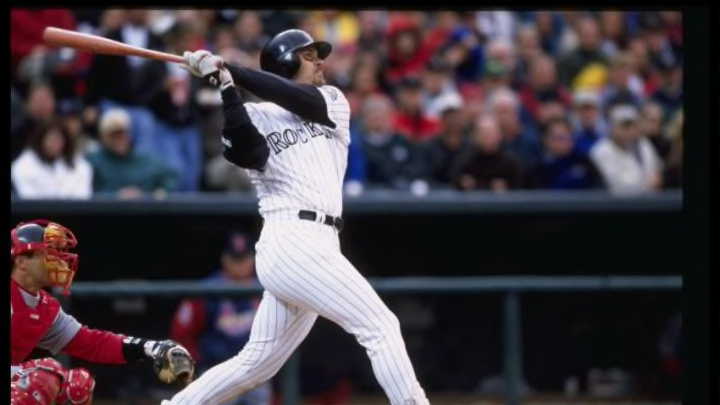

From these humble beginnings, Walker blossomed into one of the most feared hitters of his generation. He finished his 17-year career with 383 home runs, more than 1,300 RBI, and a .313 batting average. His numbers were those of a player destined for the Hall of Fame from the moment he retired.

https://twitter.com/FanSided/status/1219769734838620161

But one thing always held Walker back: the fact he spent the majority of his career playing in the friendly hitting confines of Coors Field with the Colorado Rockies. Walker hit .348 at home (.278 on the road), with 47 more home runs and an OPS more than .200 points higher. The guardians of Cooperstown—the writers of the BBWA—punished him for it; just five elections ago, Walker gained only 15.5 percent of the vote.

On Tuesday, he finally crossed the 75 percent threshold with six votes to spare, receiving 76.6 percent, because voters began to appreciate what he did away from Coors Field.

Consider his 1997 MVP season when he hit .346 on the road with a higher OPS than in Colorado and with nine more home runs. Of his more than 8,000 career plate appearances, only 2,500 came at Coors Field. In the eight seasons he spent with the Rockies, he still had a .906 OPS on the road.

Walker played his first six seasons in Montreal, averaging 82 RBI with a .293 batting average over the last four of those seasons. He has the sixth-best OPS in baseball over the last 50 seasons. Among right fielders, he ranks 12th all-time in OPS, ahead of such Hall of Famers as Tony Gwynn, Dave Winfield and Vladimir Guerrero.

Over his peak 11-season span between 1992-2002, he was fifth in the league in batting average, fourth in slugging percentage and sixth in WAR. Only three players had a better OPS than Walker, and two of them are Barry Bonds and Mark McGwire who are linked to performance-enhancing drugs.

https://twitter.com/FanSidedMLB/status/1219768373107744774

The other is a player who will come up against the same Coors Field bias that plagued Walker for many years, his former Rockies teammate Todd Helton. The former first baseman earned 29.2 percent of the vote in his second year of eligibility, a sharp increase from the 16.5 percent he earned in his first year on the ballot in 2019.

Unlike Walker, Helton played his entire career in Colorado, retiring in 2013 with 369 home runs and a .316 batting average. In his five peak seasons (1999-2003) he hit .343 and averaged 38 home runs and 126 RBI per season.

Like Walker, his numbers were better in Coors Field, but it doesn’t mean he still wasn’t a Hall of Fame-caliber player. In his best year, 2000, he flirted with .400 in Denver but still batted .353 on the road with a 1.074 OPS.

https://twitter.com/Cdnmooselips33/status/1219691612047052800

Walker had been passed over so many times he was prepared for it to happen again this year. “I think I was quoted earlier as sending something out that I didn’t think it was happening. I actually truly meant that,” he said on MLB Network following the announcement. “I had the numbers in my head and was prepared for no call. And then the opposite happened, and that call comes and all of a sudden you can’t breathe.”

His election tears down two stereotypes: that Canadians can’t play baseball, and players who spend the majority of their career in Colorado aren’t real Hall of Famers.

Walker is a trailblazer on both accounts.

Helton and the next generation of Canadian ballplayers will look back on Tuesday as the day new opportunities for them opened up, thanks to Walker.