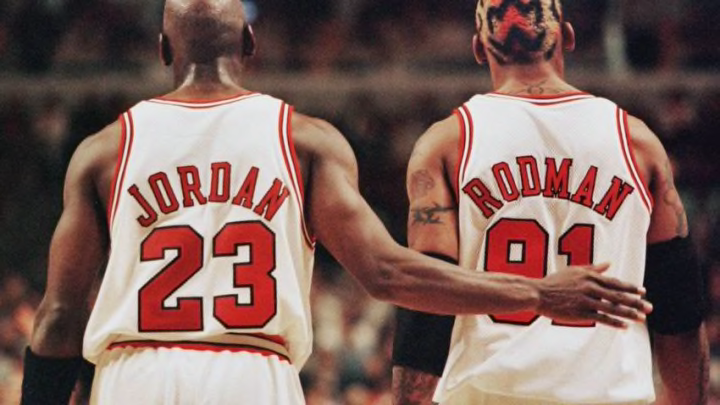

As The Last Dance — ESPN’s 10-part docuseries on Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls — sweeps the nation, it’s the perfect time to reflect on the mercurial and extraordinary career of Dennis Rodman.

We, as people, tend to remember what sticks out.

Important, exemplary, or unusual moments and individuals transcend the cloudy annals of time and forge their impressions on history. The squeaky wheel gets the grease and a head of hot magenta shines in brilliant contrast to a sea of earth tones.

It’s easy to associate Dennis Rodman with his avant-garde, tattoo-laden, makeup-wearing, multi-pierced façade during a period when individuality wasn’t celebrated like today. Or the rock ‘n roll lifestyle of partying all night, dating Madonna, and marrying Carmen Electra (in addition to two other broken marriages).

If you asked 100 people the first thing they think of when Rodman gets mentioned, most would probably say his wild, polychromatic hairstyles or the time he wore a wedding dress to his book signing. Others might recall when he kicked the cameraman or his bizarre diplomacy with North Korea.

The first thing that always comes to mind for me is the image of him diving out of bounds for a loose ball, completely parallel to the hardwood. Rodman routinely sacrificed both his body and the vanity of scoring points, just doing what it took to win.

He gave zero f***s.

I remember hating Rodman growing up because of all the sideshow buffoonery and the fact I rooted for a rival team the Bulls consistently ruined. But if he ever suited up for the Knicks, he probably would have been my favorite player.

A litany of technical fouls and tantrums marring the latter half of his 14-year career — really 12 years if you’d rather forget the combined 35 games between his twilight stints with the Lakers and Mavericks — partially overshadow his vast on-court contributions.

Behind the antics lay a pure basketball virtuoso. He wasn’t a superstar by standard definition, but a superstar in two facets of the game: rebounding and defense. Rodman had an inherent nose for the ball and insane sense of how to position himself. He outworked everybody else on the floor and that non-stop motor pushed him to the top.

In the ‘Rodman: For Better or Worse’ 30 for 30, Isiah Thomas described him as a rebounding genius. Rodman saw it at an advanced level and understood it on a higher plane. He was A Beautiful Mind for grabbing boards. Watching him rebound was probably what it felt like watching Shakespeare write Romeo and Juliet or Da Vinci paint the Mona Lisa.

Diving into his Basketball-Reference page brings the same eccentricity as his highlights. Once you read through his bevy of ridiculously amazing nicknames, you see he came into the league as a 25-year-old rookie out of Southeastern Oklahoma State University — the lone player to ever make the league from there. Of course, he made it to the NBA so late because he didn’t really play sports growing up, had an 11-inch growth spurt after high school and was recruited while homeless in his early twenties.

Rodman is anything but orthodox. He won five championships, made two All-Star teams, seven All-Defensive First-Teams, collected Defensive Player of the Year twice and entered the Hall of Fame in 2011. He sits 24th all-time in total rebounds and fifth in offensive rebounds. He led the NBA in rebounding for SEVEN STRAIGHT seasons from 1991-92 through 1997-98. Nobody ever matched that streak and only Wilt Chamberlain led the league more often, doing it 11 times.

He’s currently second all-time in rebounding percentage while holding the single-season record by a wide margin. Rodman’s feats are even more impressive once you consider his 6-foot-8 (on a good day) stature made him severely undersized during the golden age of centers, an era where every team deployed multiple goony 7-footers flanked by hulking power forward sidekicks.

Aside from being a savant of the glass, he elated in shutting down the opposition’s best big man. Rodman antagonized and played the provocateur. I have vivid memories of him pulling the chair on Karl Malone and doing whatever this was in the title clashes with the Jazz.

Few players impact the game so significantly devoid of scoring or even taking shots for that matter, but Rodman was an exception. He averaged 5.8 attempts per game over the course of his career and that dipped to 4.8 attempts during his three-year run in Chicago. He didn’t even average six points per game in any of those seasons but that run non-coincidentally coincided with the Bulls’ second three-peat.

Doing copious dirty work meant Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen wouldn’t have to, vitally lifting them to an even higher level. Every time he snared a rebound, dove into the stands or frustrated an opponent, meant Chicago inched closer to a championship. He didn’t care about stats, just about being a winning teammate.

Rodman’s colorful exterior and mercurial volatility will be remembered, but his ascension to unconventional NBA stardom should never be forgotten.