FanSided Reads: Stealing Home is a look at Dodger Stadium and the creation of L.A.

By Micah Wimmer

Eric Nusbaum’s Stealing Home is a wonderful book about the building of Dodger Stadium, the Red Scare, immigration and so much more.

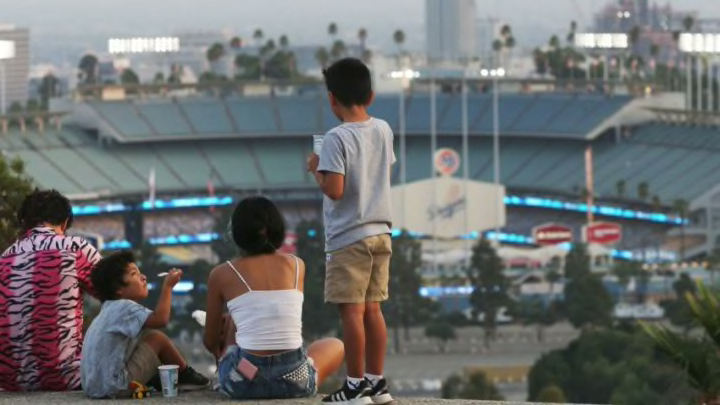

Dodger Stadium was envisioned as more than a ballpark. Team owner Walter O’Malley agonized over every imaginable detail during its planning and construction, creating dozens of index cards with a variety of ideas on how to make this stadium for his recently transplanted team perfect. It would have been a failure in his eyes if it was a place fans only came to watch games, as if it served no other purpose. No, the stadium was supposed to be “a destination in and of itself,” in the words of Eric Nusbaum in his debut book, Stealing Home. If you’ve ever attended a game there, or seen it on television, with the San Gabriel mountains overlooking the outfield wall, it would be easy to think O’Malley succeeded. It was a momentous undertaking; eight million cubic yards of earth had to be moved and $20 million spent to fulfill his vision. A whole book could be written about the construction of the stadium, but Nusbaum’s work is less about the stadium itself than how it came to exist in the first place and what had to be erased, who had to suffer, in order for millions of fans to exult while watching their beloved Dodgers there.

To achieve this, Stealing Home tells three separate but connected stories simultaneously, focusing on two individuals and a baseball team moving across the country, showing the way they overlap and impact one another. It offers us the life story of Abrana Arechiga and her family who came to Los Angeles from Mexico, establishing a home in Palo Verde before having to fight to keep it — a battle they would ultimately lose. Parallel to that narrative is the tale of Frank Wilkinson, a public housing advocate who wanted to build a massive complex in the neighborhood where the Arechigas lived until money and Cold War politics got in the way. In the aftermath, Wilkinson’s life fell apart and he found himself in prison, a self-made martyr for his beliefs. And then there is the story of the Dodgers moving to Los Angeles as this southern California city attempts to create itself, writing its own mythology in real-time, seeing a major league baseball team as the next step in its evolution

With all these different threads, Stealing Home is a book that is dense but never difficult. It is truly astonishing just how much ground Nusbaum is able to cover in this relatively brief book. In addition to the main narrative, there are numerous fascinating asides including ones about the Zoot Suit riots of 1943, the Pacific Coast League’s bribery scandal, and Los Angeles’ 1953 mayoral election. Nusbaum also profiles several notable figures of this time who have either faded into the background now or never were especially famous in the first place — persons such as Ignacio Lopez, a publisher and writer who fought tirelessly against racism; Fritz Burns, a man who fought to kill public housing in the hopes of building his own homebuilding empire; and Rosalynd Wyman who became the youngest city council member in the city’s history and helped push for the city’s acquiring a major league team as strongly as anyone. All these detours help bring the central narrative into clearer focus, providing a greater picture of the world the primary figures lived, and the people and concrete forces who undid them.

The chapters are almost all quite brief — averaging just a few pages each — allowing the narrative to flow quickly so the reader is not overwhelmed by information about any particular topic at any one time. Also, this means that if one is particularly engaged in one specific aspect of the story, it will not be long before it is returned to.

Stealing Home is a rich and thoroughly researched look at Los Angeles history

One of the most striking things about this book is the depth of research that is evident on every page, making it seem as if Nusbaum was a resident of Palo Verde all those years ago or in the courtroom when Frank Wilkinson testified instead of reporting on it decades later. In the back of the book are 18 pages of notes regarding his sources and the hundreds of hours he must have spent interviewing family members and other historians, and poring over books, newspapers, and pamphlets are evident in every sentence.

Nusbaum writes in the preface that one of the book’s major themes is “how we rewrite history to suit our own present aims.” Each of the major figures in this book does that time and time again, creating a narrative that reifies particular values and priorities, telling a story that is true but perhaps only from a certain vantage point. Of course, a corollary to this is how particular stories win out, the way the powerful can establish the official story, bending history and the messiness of reality to their whims. But perhaps even more important, and less noted by the general public, though thankfully not by Nusbaum in this work, is the question of who has to be cast aside for these narratives to take shape and coalesce — the lives and homes and families lost for the sake of another’s comfort.

While Stealing Home is ostensibly a sports book, it is really much more than that, hopping between topics with a felicity that shows great skill and thoughtfulness. And the stories within, while being decades old, are disturbingly relevant today. Stadiums are still being built in areas that displace longtime residents, splintering neighborhoods and removing traces of history that cannot be replaced. While O’Malley at least used private money, many stadiums constructed today rely on public money through taxes that only benefit the facility’s private owners. It’s all part of the shift from “‘community modernism’ toward ‘corporate modernism’” that we see playing out again on a larger stage today as more and more industries are privatized, leaving millions behind in the process.

Furthermore, the horrifying rhetoric and violence — both physical and material — towards immigrants has scarcely waned today with xenophobia as rampant as ever. Also, the sections about HUAC and the Red Scare seem particularly poignant now in light of the recent criminalizing of protests by an administration eager to hamstring any potential dissent. It’s a sad, but important reminder of how much remains to be accomplished — of how in spite of all the ostensible progress that has been made since Dodger Stadium initially opened in 1962, that the fight for justice is one that is never fully accomplished but always in progress.

Loving Sports When They Don’t Love You Back. light. FANSIDED READS