New biographies of champion boxers Carlos Monzon and George Foreman showcase the glory and pitfalls of achieving success in the ring

The world of boxing is full of larger-than-life characters, men who are compelled by a combination of desperation, desire or some combination of the two, to devote themselves to the fighting life in hopes of creating themselves anew. For the rare few who do find that glory, there are even fewer who do not suffer a subsequent fall. Two new biographies of two of the best boxers of the second half of the twentieth century have been recently released, capturing those stories of epic rises and all too familiar falls

Don Stradley’s A Fistful of Murder: The Fights and Crimes of Carlos Monzon is the fifth installment of the Hamilcar Noir series which looks at where the worlds of crime and boxing intersect. Stradley’s book is a biography of Carlos Monzon, a name not likely to be recognized by most readers today, though he was a major celebrity in Argentina during his lifetime and perhaps the country’s greatest boxer ever. He was the middleweight champion of the world for several years, rising from deep poverty in the province of Santa Fe to become one of the best pound-for-pound boxers ever

Monzon lived an ostensibly glamorous life as champion, becoming friends with French movie star Alain Delon, dating an Argentinian actress, and appearing in movies himself all while openly flaunting his wealth. Yet Monzon was never able to tame whatever demons resided within. Stradley does not pull any of his own punches when writing about Monzon, describing him as “just an angry, illiterate man consumed by petty jealousies and the shame of his background,” and a narcissist who “was never far from becoming completely unhinged.” Those less savory inclinations arose many times as he was consistently abusive to the women in his life, culminating in the murder of his estranged wife, Alicia Muniz. It was unsurprising but still horrifying, a situation that had been enabled by countless people eager to partake in his glory either up close or from afar. As Stradley notes, a successful Monzon was good for the press, good for the country. He was able to act with impunity since “the image being created in the press, that of the glamorous boxing champion basking in newfound fame and wealth, created enough smoke around Monzon to deflect most public scrutiny

In spite of its often gruesome subject matter, A Fistful of Murder is a breezy and enjoyable read. While it may not be a fully definitive biography of Monzon, it’s a very good overview of his life for the uninitiated. The book is most successful when examining the status he obtained in Argentina and why so many were unable to stop seeing him as a hero even after he was revealed to be a murderer

It is an interesting story about the distinct advantages celebrity provides, and how it can often shield one from justice. Even though Monzon was a consistently abusive man throughout his life and was convicted of his wife’s murder, there were still many in the country who remained sympathetic to him in light of the success he had achieved in the ring. He was even given frequent furloughs, allowing him to leave prison on the weekends despite his violent nature. It was on one of these weekend escapades that he died in 1995, in a car accident. As Stradley writes near the end of the book, Monzon is proof that “some of us are so badly in need of an idol that we’ll even praise a killer.”

Boxing is a backdrop for familiar stories of success and failure

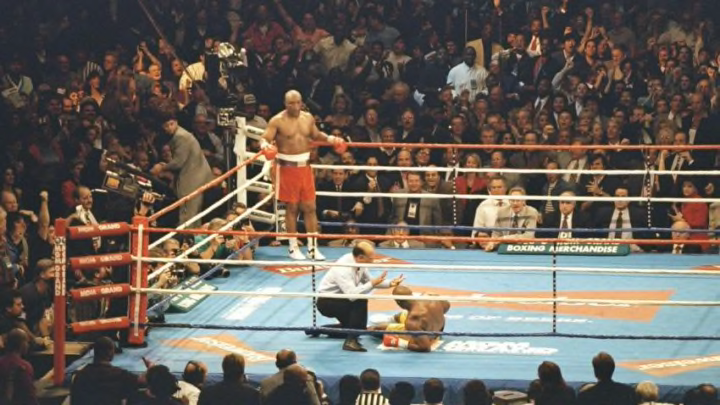

Unlike Monzon, George Foreman needs no introduction. Even those who have no interest in boxing or were born well after his 1970s prime are familiar with him due to his ubiquity as a celebrity and spokesperson selling the countertop grill bearing his name. Yet it’s an unexpected turn for one who grew up poor in Houston, dropped out of school at 15, and became a petty criminal afterward. Author Andrew R.M. Smith captures all those twists and turns in his book No Way But to Fight: George Foreman and the Business of Boxing, from Foreman’s childhood to his brief reigns as heavyweight champion, showing what made them possible for this most unlikely figure.

Smith’s examination of Foreman is less of a straight biography than it is a look at the changing business of boxing from the 1960s to the 1990s, using his career as a lens through which to look at those shifts. This is a successful approach at points, particularly when looking at how the Job Corps helped set the stage for his boxing career and why so many of his major fights took place overseas. It provides a depth to the topic at hand and any reader is sure to learn a ton about the details of his life and career here. The problem though is that the reader gets a better sense of the world Foreman inhabited and how he moved within it than they do of Foreman himself. His relationships with his wives and children are barely mentioned and little sense of his private self ever emerges.

Instead, the book focuses on Foreman as a public figure, the way his persona shifted throughout the years to adapt to a changing America, first as a boxer trying to get a shot at a heavyweight championship bout then as a marketer attempting to create a name for himself outside of athletics. From the young flag waver at the 1968 Olympics to his tough-guy persona of the early 1970s and from his foray into ministry to his comeback as a more affable figure, Smith chronicles all of these changes and shows why they were necessary and how they helped him become an iconic and indelible figure in American culture. As Smith sees it, it was not Foreman’s success in the ring that made him an icon, but rather it was these transformations that enabled him to get a shot at the heavyweight title in the first place and then allowed him to remain in the public eye long after his fighting career ended. This makes Smith’s book a certainly worthwhile and thoughtful read, though perhaps one more of interest to serious boxing fans than casual ones with a passing interest in Foreman’s career.

Each of these books does a good job showing the potential glory and pitfalls that come from being a boxer. Foreman and Monzon both grew from poverty to the heights of the fighting world yet only the former was able to parlay his glory in the ring into similar success outside of it. In this regard, these stories are ones of reinvention, of how two men remade themselves from situations of deprivation into world champions. But if Foreman’s story shows the importance of continuing to do so, of remaking oneself as times and situations change, Monzon’s shows the potential pitfalls of failing to do so. They are both fascinating figures and while neither of these biographies feels definitive, they are both engaging reads worth picking up for any curious about them or the world of boxing.