Everyone from Karl-Anthony Towns to Anthony Davis has reminded us how difficult and impactful it is to achieve joy in the NBA right now.

Any team you’ve ever rooted for has aspired to joy.

For sports teams, it’s a quality just out of reach, the value of which is espoused through an oral tradition as old as competition. On the podium, as they raise the trophy, it’s an aphorism that gets tossed around every year across multiple leagues and games. Throughout a season, words like momentum, accountability, or the metaphorical “blood, sweat and tears” all sort of gesture broadly toward the idea of joy. Not unlike any other workplace, the goal is to love what you do so much that it doesn’t feel like work, to connect with your coworkers or teammates to an extent that they feel like partners in a shared mission, or — maybe even better — family.

That, to a great extent, is why coaches exist, and why we see acquisitions highlighted by the idea that a player might bring veteran leadership to a group. All these things are done in an effort to generate joy within a profession that, while lucrative, involves the grind of excessive travel, immense physical exertion, and often very little control over your path.

That amalgam of stress and aspiration has been deep-fried in public health regulations and overall grief over the past year in the NBA, making a nearly impossible task even harder. How does a group of athletes come together joyfully when they often can’t even spend time together as teammates, rarely get positive reinforcement from fans, and watch the financial infrastructure of their league decay? This is true of nearly every sport today, but likely because of the intimacy of the NBA, the reality rings more loudly there.

Why is joy such a powerful and elusive force in the NBA, this year more than ever?

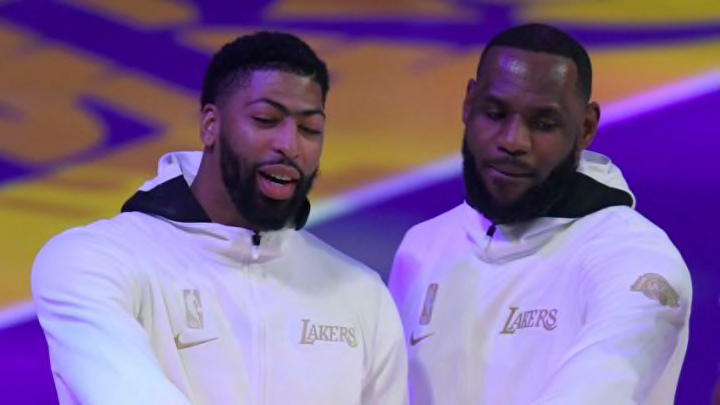

Altogether, it’s given the rare team that can find joy an even stronger advantage while also magnifying its absence among those groups still searching for it. Take the Anthony Davis publicity tour from earlier this year, in which Davis made a genuine point of preaching the importance of joy, and how it helped him become his best with the Lakers.

“When you’re losing, you don’t realize that you’re not happy,” Davis told The Bird Writes. “You made a ton of money. You can do whatever you want. You can live this lifestyle, quote-unquote ‘The American Dream,’ but losing sucks. I {realized that} I’m not happy. I want to be happy. And you kind of go through these times where it’s like, do I really want to play basketball? Am I really good enough? You start doubting yourself because you’re not happy.”

Davis went on to explain how nagging injuries, playoff losses, all the little stuff that we associated with him in New Orleans sapped what little joy he had after years of disappointing seasons with the Pelicans. It doesn’t seem like it was necessarily Los Angeles that helped Davis rediscover joy as a basketball player — though winning surely helps — but more just being able to leave New Orleans.

This season, the departure of a star had a similar effect not only on him but his team as well. Since James Harden has left Houston, he has found a way to sacrifice again like he never had to with the Rockets, setting up his teammates and playing with far more energy than he did before the trade. But most impressively, the Rockets have found another gear. Early in February, amid a six-game win streak, veteran guard Eric Gordon and first-time head coach Stephen Silas both agreed that “fun” was the key ingredient in the team’s improved play.

“What makes it fun is everyone coming in with an unselfish attitude every day and everyone has a chip on their shoulder,” Gordon told Kelly Iko of The Athletic.

Silas agreed: ““I’m having fun. I’m not gonna wait 20 years to be a head coach and not have fun doing it.”

Call it the Ewing Theory or just more evidence that Harden can be a challenging teammate, but regardless, the results prove that something clicked for the Rockets. Starters Victor Oladipo and Christian Wood are out now, but Houston is competitive every night and has put together a top-five defense out of spare parts.

To understand why it’s so remarkable that the likes of Davis and Silas have found joy this year, most of us won’t have to look far. The world is engulfed in turmoil and trauma, with a pandemic turning up the temperature on many of the crises facing us right now. It’s no easy time to roll out a ball and play a game with passion and thrill. Heck, it’s hard to even have the emotional capacity to extend a helping hand to a neighbor or colleague who needs it.

But more specifically, the NBA is full of harsh examples as well. There may be none better than the case of Karl-Anthony Towns, who lost his mother and six other family members to COVID-19 last year before becoming infected himself. Towns is back on the court now but has been open about how difficult it is to compete when many of the people he used to play for are gone.

“It always brought a smile to my mom and it always brought a smile for me when I saw my mom at the baseline and in the stands watching me play,” Towns told reporters in December. “It’s going to be hard to play. It’s going to be difficult to say that this is therapy. I don’t think this will ever be therapy again for me.”

Less devastating but also fairly challenging is the state of the Toronto Raptors. Because of travel restrictions between Canada and the United States, the team has been forced to play its games all season in Tampa, Florida, far away from their homes and likely their families. The league recently announced the plan would stay in place indefinitely.

Back when the decision was made, general manager Bobby Webster described the need to come together to find joy.

“I think you really understand the meaning of being part of a team,” Webster said. “Now it’s our collective health, our collective well being, and so I think that sense of belonging and unity is really important for a time like this where it feels like we have each other’s back. And we’re all looking out for, you know, the greater good.”

They may be finding it now, after a string of victories pulled them above .500 for the first time all season, but the Raptors quite understandably started slow this season.

What makes such words particularly gutting is that NBA games are put on in large part to give viewers joy. Sport courses through many parts of our society, but the core purpose it serves is to engage and uplift fans. It’s a game after all — a hell of a game. When those who play it have their joy sapped, it shows, and it can feel as if the jig is up on the whole setup. A basketball game starts to feel like quite a small thing, even if it is a job for those involved.

There may be an instinct to claim that whoever can discover and maintain joy in this chaotic time will have the best chance to be crowned champion, but neither the Dodgers nor the Bucs, our two American champs from leagues that did not create Bubbles, prove that much. The best team will win, as they tend to. But if you buy into the idea that there’s more to this whole thing than just Ws and Ls, the joy factor is pretty important, too.

Does it feel the same to root for a team that is somber and defeated? It’s not really something we have to confront most of the time, but the fact that those involved are so publicly confronting their own relationship to the game and their professions means we should, too. The highs of this season have felt a bit sweeter for the best, and the stakes of the low points hurt it even worse. Everyone is searching for joy in the sport, but the reality is that in this time, it’s out of their control.