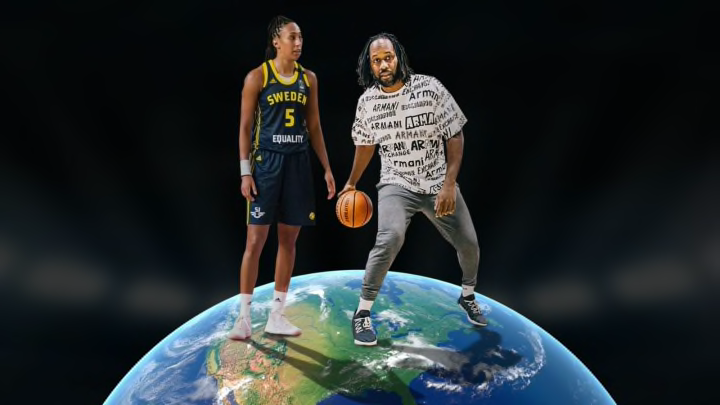

Tremaine Dalton and Kalis Loyd are working to build a global infrastructure to help girls and women participate and succeed in basketball at all levels.

Women’s basketball has a problem. It’s not that girls and women don’t like playing basketball, because they do — the Women’s Sports Foundation has research that backs up their claim that at least two in five girls in the United States are playing sports right now. It’s not that girls are inherently more fragile or less interested in competition than boys because they aren’t — in 2008, researcher Joyce Benenson studied 87 four-year-olds and found that young girls were just as competitive as their male counterparts, they simply deployed different tactics in pursuit of victory.

It’s definitely not that there aren’t talented girls and women around the world who love to play basketball. The WNBA currently boasts 12 women’s teams, and each team has 12 women on a roster. That means competition is tough; the league is extremely cutthroat, and there’s not room for everyone who can play to actually make it to a team.

Unfortunately, it seems nearly impossible for WNBA players to make a career out of playing in the league alone. In 2018, The Guardian reported that approximately 90 out of 144 of the league’s players spent their offseason playing professionally in Europe, to often mixed results. Women who are internationally double-dipping have an increased risk of injury since they find themselves playing all year instead of the typical seven to eight months in the States. This phenomenon isn’t strictly limited to American women traveling overseas to play; the reverse happens as well.

Kalis Loyd is a Swedish basketball player who has played professionally in Europe for eight years. During that time, she’s been on the roster in four countries: Romania, Italy, France, and Spain. It’s fair to say she was born into basketball; her father, Otis Loyd, moved from New York to Sweden to play professional basketball before moving on to coach Copenhagen Denmark, and her mother played as a young girl. After her parents divorced, Kalis spent most of her time with her mother in Malmö, Sweden, where she began playing the game with boys from her class at the age of seven.

Loyd divided her time between Denmark and Sweden, hopping on a train each weekend and training with a girl’s team that her dad coached. One thing led to another, and after Loyd’s mother suggested her dad begin coaching her, Kalis didn’t look back. Her basketball credentials run deep: in ninth grade, she joined her school’s varsity team, and she played in the European Championships a year later. When it came time to leave high school, American colleges came calling. She was ready.

After settling on Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, Loyd joined the school’s team for the 2009-10 and spent four years starring for the program. . To this date, she is the university’s all-time scorer with 1,967 points, and the school retired her jersey in 2018. College ended, and Loyd found herself back in Europe.

This migration from Europe to the United States and back again isn’t uncommon; professional athletes in Europe often opt to play college sports in the US because the same athletic skill isn’t often found at the college level in their home countries. However, women who play basketball have found themselves in a position that their male counterparts just haven’t: struggling to make ends meet.

As you might have guessed, the explanation starts with money. Albert Lee, a writer at Bullets Forever, explains:

“The relationship between the WNBA and European women’s basketball is that a significant number of WNBA players also play on European professional teams in the fall and winter. They do so to make more money. Before the current WNBA CBA (2020 season to now), most players didn’t make $100,000 a year and were able to supplement their earnings on a European team. If the player is an MVP superstar, they can earn a salary in Europe that is often double, triple or more of their WNBA salaries. Phoenix Mercury G Diana Taurasi earned about $1.5 million per year to play for UMMC Ekaterinburg in 2014-15, about 15 times her WNBA salary at the time.”

However, despite that earning potential, Lee believes that most WNBA players would rather play at home if they could. The Undefeated has noted that in 2014, nearly three-quarters of all women in the WNBA were also playing in leagues across the Atlantic, a phenomenon that’s just not seen in the NBA at all. The minimum player salary for NBA players participating in the 2020/2021 season is $898,310. Entry-level WNBA players on the other hand, are looking at a minimum salary of $57,000 — and only if they have at least two years experience playing in college prior to joining the league. NBA players get that $898,310 without any college experience required at all, as long as four years have passed following their participation in high school basketball.

Building a new basketball program from the ground up

In 2019, Kalis Loyd met European basketball trainer Tremaine Dalton, an American who founded The Process Basketball in 2017. The multi-armed company has two branches in Paris, France, and Melbourne, Australia, and Dalton is actively developing domestic programs in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and internationally in Panama, Japan, and China.

The Process Basketball has three key elements: Dalton trains elite-level players wherever they need him; he’s worked in locations as far-flung as Haifa, Israel and Orlando, Florida. His players also hail from countries all over the world, including South Sudan (Emmanuel Malou, who has trained with the Sacramento Kings and the Warriors before moving on to Europe and Iraq) and Estonia (including Kristjan Kitsing and will work with Kregor Hermet later this year). He’s also been recognized as one of the world’s top one-on-one players after winning the Red Bull King of Rock one-on-one contest in 2011 and is one of the few coaches who can combine isolation-style basketball with European playsets.

Perhaps most importantly, The Process Basketball actively develops community initiative programs in partnership with the United States government and governments around the world and then brings those programs to fruition. From helping combat gun violence in his hometown of Grand Rapids to coaching disabled children in Melbourne to coordinating with the US embassy in Estonia to bring Russian and Estonian families together for healing via basketball, Dalton has made working with communities to uplift and inspire the youth the heart of The Process Basketball’s mission. Now, he wants to turn his energy towards building youth basketball programs for girls, and he recognizes that the problem is at least three-fold: more opportunities need to exist for girls and women who play, girls and women need more role models in sports, and women’s programs just need more money.

Anjelica Ostrea, who founded the American non-profit Girls Youth Basketball, agrees that money, or the lack thereof, causes even more insidious problems for athletic girls from a young age. Her organization studied how involved girls and boys were in youth basketball from 2006 to 2010 and found that 40 percent of adolescent boys compared to 25 percent of adolescent girls were playing basketball, and the number of girls involved in basketball in high school drops as girls age.

“Female professional sports compared to male professional sports has a huge wage gap. Besides golf and tennis there is really no financial upside to women professional sports. Most Americans pursue a career with money as a big factor; unfortunately for women being a professional athlete is not one of [those careers].”

However, Ostrea is quick to point out that money isn’t the only culprit, which Dalton and Loyd both know all too well. Unfortunately for girls who are interested in pursuing a career in professional basketball, there aren’t a lot of avenues available. There aren’t many professional teams in the United States or in Europe, and girls’ sports haven’t always received the same level of funding and attention. The introduction of Title IX in 1972 offered a boost, giving universities and schools federal dollars to fund programs for girls to combat sex-based discrimination, but as a June 2020 study published by The Sport Journal found, most of those programs end after five years or less.

That same group of researchers also noted that in the 1990s, men’s programs received the overwhelming majority of funds dedicated to athletic scholarships, along with 83 percent of recruiting funds and 77 percent of operating budgets. Money creates opportunities, and as Ostrea noted, opportunities for girls are still lacking.

“Another big factor to the lack of girls pursuing professional sports is opportunity. Not only are there limited professional sports and teams for women to pursue, but the steps towards getting there are minimized as well. With the lack of access from youth up until college this makes it difficult for females to engage in sports and yet alone pursue a professional career in it.”

These problems aren’t unique to the United States. It can be difficult to get a grasp on what girl’s and women’s basketball is like in Europe; unlike the United States, there’s not just one professional league. Nearly every country boasts its own professional team, and there are two dominant leagues that include players from across the continent: the Basketball Champions League and the EuroLeague Women. Overseeing everything related to basketball outside of the United States is the International Basketball Federation, or FIBA: a dominant global force that boasts teams from 213 federations.

Elisabeth Cebrián-Scheurer played professional basketball in Spain for 17 years and is currently the face of women’s basketball for FIBA. As the Head of Women in Basketball And Special Projects, part of her work includes learning more about cultural attitudes about girls and women in sports across the world.

When it comes to knowing how many girls in Europe are playing basketball, FIBA doesn’t have exact numbers. But the organization is spearheading two projects that could change the game. Its Women in Basketball study was conducted in 2018 and revealed a troubling statistic that their American counterparts know all too well: girls are dropping out of youth basketball before they even hit their teens. Cebrián-Scheruer believes 60 percent of European girls will leave the sport before they hit their 13th birthday.

To combat that, FIBA has launched its brand new “Her World, Her Rules” campaign that specifically targets these girls. Cebrián-Scheruer says the goal is clear: FIBA hopes to “sustainably grow girls’ participation in basketball by recruiting more players at school age through various activities and increase the visibility of basketball.” Right at the top of the campaign’s goals is to increase participation of girls in basketball, to find and promote more female role models in professional basketball, and make sure basketball is the first sport European girls want to play.

Luckily, Dalton and Loyd are looking to create exactly those kinds of opportunities for girls and women in basketball.

Dalton believes that his ability to really connect with players at all levels and to teach them to find and claim opportunities for themselves is what makes his program stand out. After all, the accessible nature of social media makes it easy for just about anyone who knows how to dribble a ball to set up an Instagram account and start a YouTube page and call themselves a trainer; Dalton has built and nurtured a program that puts his clients and all of their needs — mental, emotional, and physical — at the heart.

Trainers with a basic understanding of the game, a handful of basketball skills, and a lot of knowledge about marketing can use Instagram and other social media platforms to become celebrities in their own right, but that’s not a path he’s interested in taking. Dalton approaches things differently; as a one-on-one champion, he teaches the skills that he’s already an expert at to a select group of players who are already at the top of their field. He’s not teaching all of basketball in an attempt to monetize his lessons online, he’s teaching one form of the game that he knows inside and out: one-on-one basketball.

“What separates me from other trainers is that I’m very client-specific. I really stick with the same 10-15 professional clients every year, so I can really build an interpersonal relationship with each client. My training goes beyond just basketball; it even goes beyond the athlete’s personality. It includes their own ups and downs, their fears. We work together and combine those things [and experiences] to make the players the best they can be. Basketball is really based on moments; to capitalize on those moments, you have to be emotionally strong. I harp on teaching the ability to be emotionally and mentally strong on the court, which will make sure players are in control of themselves off the court.”

Kalis Loyd knows this firsthand. As a trainer, Dalton has been the perfect match, and his emphasis on the physical as well as the mental has helped her work through her own professional and personal struggles. People understand that sports are about the mental and emotional just as much as they are the physical; the American-based National Youth Sports Health & Safety Institute (NYSHSI) published a 2012 study that spoke to exactly this.

“…youth who play sports are more likely to have better mood and perceptions of themselves, feel competent, experience physical and psychological well-being, be better able to control their own behavior, develop positive social skills, and have greater life satisfaction.”

Part of Dalton’s work is to build on the emotional skills that players are introduced to as children and to remind his clients they’re more skilled and powerful than ever.

Loyd says, “He makes you feel comfortable and confident, even though I’ve struggled many times throughout our workouts. He doesn’t only challenge your skills, but also [challenges] your mindset and confidence. I’ve never met someone who boosted me the way he did, but didn’t do it to make me think I’m something I’m not. In all actuality, he brought out the high-level player I am and [showed me] how to showcase that through my skills.”

The feeling is mutual. In 2019, Kalis was preparing for a championship game against Russia, and she was feeling unsteady. She called Dalton for a boost, and he delivered, just as he’s done before. She was named the MVP of the game. It sounds simple — after all, the two just jumped on the phone — but sometimes that kind of boost is what a male or female player needs. Dalton explains that it’s just what he does.

“Basketball goes beyond just physical training and your skillset. You can actually talk somebody into doing well. At the time, Russia had one of the strongest teams in the world.”

For him, Loyd was never not going to do well that night. He’s seen her grow exponentially as a player and as a woman in two short years.

“She’s a much more confident player and person in general, and she’s taken more emphasis on leadership and taken more chances in her career. Especially during covid, that energy is needed now more than ever, both on and off the court.”

With their passion for basketball obvious, it was only a matter of time before Dalton and Kalis put their heads together and began brainstorming. Unlike some people, Dalton found that the international woes coronavirus inflicted on the world in 2020 were a boon to his business; the extended period of lockdown forced him to literally stand still and think about new ways to innovate and develop. One day it hit him: everyone knows the way Americans and Europeans approach girls and women’s basketball needs work… so why not do the work alongside one of the most talented European basketball players he knows and make that change happen?

Soon, the idea to host an exclusive girl’s camp in Loyd’s hometown of Malmö began to come to fruition. The plan is simple: 10 girls will join Loyd and Dalton for three days in early July of this year. They’ll work on basketball skills, but they’ll also work on how they see themselves as girls and women in a world dominated by boys and men. Instead of trying to teach and train girls the same way he teaches and trains boys, Dalton envisions a camp where girls are allowed to tap into their natural ingenuity, impulses, and power. Instead of telling girls to toughen up and play like the boys, the camp he and Loyd are planning will give girls who attend the space to explore their identities in the world of basketball, and to construct their own framework of what it means to be enthusiastically female and to be an athlete.

The camp’s programming will combine what one might expect from a typical basketball camp — each day will last from three-to-five hours, and girls who attend will practice that they’re there for: basketball. But the days will also include seminars and workshops that are designed to give the young girls room to speak about every aspect of what it means to be a girl in sports; they’ll have the opportunity to hear from speakers who have been in their shoes, and emphasis will be placed on giving the floor over to the girls themselves.

Loyd recognizes the need to address mental health while simultaneously teaching girls basketball skills. Being a woman and a professional athlete is never easy, and she knows she stands out in this role. She says, “I want girls to be unafraid of the hurdles yet to come. Now more than ever is the time to speak about mental health and confidence, and [since we] have a platform to do so, it’s our obligation to help teach the next generation. I never heard of mental health when I was younger. The earlier we can start, the better kids can learn about themselves and open the door to mental health.”

She also hopes the camp opens up conversations about what opportunities could exist for women in all sports, not just basketball if only more companies would get behind them. Loyd believes that professional female athletes should be earning more in both terms of money and in terms of respect.

“A lot of [the hours] goes unnoticed. I would like businesses to offer a lending hand to bridge the gap many athletes experience once they no longer play professionally. Companies could put female athletes in campaigns for tampons, sports clothes, basically any female product, and connect and celebrate femininity and sports.”

Because ultimately it comes down to a truth recognized by girls and women everywhere: “We’re superwomen, and I think it’s time the world recognized it.”