Palace of the Fans opened in 1902 — more than a century ago — a first-of-its-kind baseball stadium that included standard modern amenities like concession stands and luxury boxes for the first time. But while contemporaries have like Wrigley and Fenway have become protected monuments, the Palace was lost to time and circumstance.

How lucky you’d have been if you found yourself in Cincinnati on April 17, 1902.

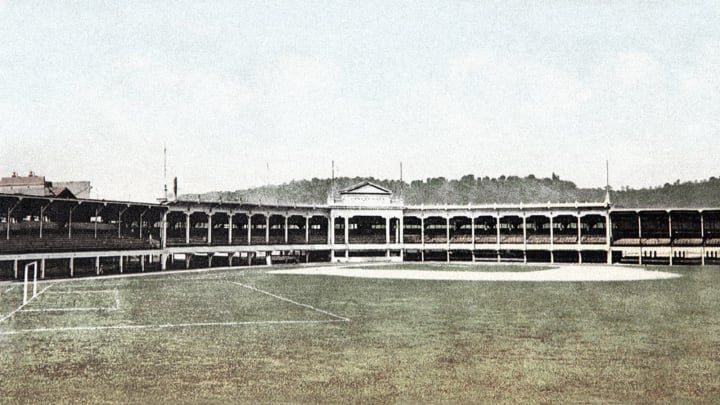

For a baseball fan — for anyone who enjoys beauty and spectacle, entertainment and joy — the entirety of the city came together to celebrate the opening of the 1902 baseball season, yes, but even more significant, the opening of the greatest baseball park ever built, a mixture of elements we haven’t seen since and forerunners of the most significant features at a baseball game to this day — Palace of the Fans.

You could have awakened in Cincinnati that day to a chill in the air, but knowing the warmth would come — high of 65 that day, spring baseball weather at its best. Take the streetcar to the game, and you would have found yourself surrounded by other Cincinnati supporters, perhaps even some of the Reds players — the very seeds of Palace of the Fans’ obsolescence could be observed on that first, glorious day, including the fact that architect John G. Thurtle, for all his singular detail work, did not include clubhouses or dugouts at the new park, forcing players to dress at home or at their hotels and come to the game in full uniform.

This day, however, it was by design, with the Reds and their Opening Day opponents, the Chicago Cubs, meeting up to travel on a designated pair of trolley cars, one for each team, leading what became a parade to the shining new park. As you approach the ballpark, the sound of Weber’s Military Band gets louder and louder. “Won’t You Come Home, Bill Bailey?”, a huge hit in 1902, is audible, and you can sing along — the song is everywhere, of course you know the words, as you jingle the quarters in your pocket. It’s more than enough to pay your way into the ballpark, with prices set at 50 and 65 cents, depending on where you want to sit, with enough leftover for concessions — and you’re going to want to eat and drink what they’re serving at Palace of the Fans.

An hour before that 3 p.m. first pitch, the players entered, the crowd rose to cheer, the band kept playing as outfielders warmed up their arms, throwing to one another, and Reds Opening Day starter Len Swormstedt, a Cincinnati boy made good, getting ready in foul territory pitching to Bill Bergen. The pair were part of a new, young infusion of talent on the Reds, most notably outfielder Sam Crawford, who hit .330 in 1901, upped that to .333 in 1902, en route to the Hall of Fame in 1957. The manager was Bid McPhee, himself a future Hall of Famer, though as a player, inducted by the Veterans Committee in 2000. After a last-place finish the year before, hope reigned across the ballpark that professional baseball’s oldest team could win its first pennant since 1882, 20 years before.

Depending on where your tickets seated you, it was possible to get a look at the man responsible for it all, Reds owner John T. Brush, to look up and take in the Corinthian columns and unparalleled architecture throughout the park that Brush himself had insisted on, a vision he’d had years earlier at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

The band stopped playing and Chicago’s leadoff hitter, Jimmy Slagle stepped into the box. The first pitch from Swormstedt came in, and the too-short life of Palace of the Fans truly began.

It is easy to think of history as immutable, the way details and large-scale changes unfolded as pure inevitability. They are not. And ballparks, for good and ill, prove it.

Witness the long life of Wrigley Field, built in 1914, treasured and preserved through the multigenerational ownership of the Wrigley family, long enough to reach the period when ballparks were, at least in some quarters, considered too sacred to destroy. Fenway Park was built even earlier, opened in 1912, and survived an extended municipal dialogue on its existence about 20 years ago.

Other parks have not been so fortunate. And it has little to do with viability. Shea Stadium came down after the 2008 season, and because the mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, insisted upon it, the Yankees tore down their cathedral, Yankee Stadium, and built a mediocre replacement (with more accouterments for the wealthy, of course) in its stead. Shea Stadium, incidentally, was built and styled in a similar way to Dodger Stadium, still with us today. Dodger Stadium, of course, came about thanks to the decision by then-team owner Walter O’Malley to abandon Ebbets Field and come west. He brought Horace Stoneham and the Giants with him, thus ending, after a few years of occupation by the Mets, the lifespan of the Polo Grounds as well.

Similarly, both the existence of Palace of the Fans, as well as its quick demise, have a lot to do with one man: John T. Brush. He’s the man who rebuilt the Polo Grounds. And had history unfolded differently, he could have been the one to save Palace of the Fans.

Brush was a department store magnate — ask your great, great grandparents about the When Store in Indianapolis — who owned a team in Indy, then when that team was declared surplus to needs by its league, the American Association, he bought the Cincinnati Reds.

Several years into his tenure, Brush traveled to Chicago to take in the 1893 World’s Fair. It’s hard to overstate how central to current and future thought each World’s Fair was — whether Chicago in 1893, St. Louis in 1914 or New York in 1964 — but it led to the kind of thinking that produced replica cityscape landmarks. At a time when streetlights were at a premium, it is easy to understand how Brush walked unsteadily — a medical condition forced him to utilize two canes over the final few decades of his life — through the so-called “White City”, built in a neoclassical architecture style and lit up at night, and determined that this would be the way the baseball fans of his team should enjoy the sport. He wasn’t the only one so inspired — a man named George Tilyou saw the very first Ferris Wheel amid the exhibitions, returned home to New York, and designed and built Steeplechase Park in Brooklyn’s Coney Island.

Brush owned the Reds but had designs on another team — the New York Giants, close to the Broadway life he and his wife, Elsie Boyd Lombard, lived in socially. Brush had met the future second Mrs. Brush after seeing her in an 1894 show, A Temperance Town. But while he waited for an opening to purchase the Giants, his Reds, struggling on the field, needed a new home after a significant portion of the grandstand at their old wooden structure, League Park, burned to the ground in 1900. That gave Brush the opening he needed to take his Reds above the efforts of other owners, as he saw it, “to keep baseball in the saloon class”, and make them a team for everyone in Cincinnati, regardless of social station.

The jewel of the stadium is one that, had Palace of the Fans been nothing more, would be memorable itself. In the southwest corner of the land on the corner of McLean Avenue and Findlay Street, Brush built a grandstand with 22 Corinthian columns, made of concrete, not wood — a lasting material that became more standard as baseball teams throughout the country looked to create permanent homes. The grandstand had the city’s name — Cincinnati — proudly carved into the facade behind home plate, so that wire service photos would be certain to note where the games were taking place. In this way, it is a combination of the most well-known baseball park eccentricities, a healthy dose of pragmatism (which led to Fenway Park’s Green Monster, created to even out the batter/pitcher equilibrium of a stadium built to live within an established city block) and executive whimsy (as was the base when young Cubs executive Bill Veeck decided to plant some vines along the Wrigley Field outfield walls).

But the ballpark pioneered many of the most significant advances, financially and aesthetically, that are found in the modern ballparks as well. Nineteen so-called “Fashion boxes”, or as we’ve come to know them, luxury boxes, catered to Cincinnati’s most well-to-do fans. The fans even had the option of bringing their carriages — horses or, in more and more cases as the decade went on, horseless — to halt right outside the boxes, which held three rows, five chairs apiece, and offered a view of the proceedings just above field level.

Luxury aside, Brush’s new park did not cater merely to the wealthy. In fact, the people of “Rooters’ Row” — reserved for the rowdiest of Reds fans — were separated only by a bit of chicken wire from the field itself, where both teams sat on benches, the best view in the house for the game. Fans could buy beers, priced at 12 for $1, so it is fair to assume the home field advantage grew louder as the afternoon went on. Whiskey was also available at the bar area, along with pickles and hard-boiled eggs, while those who were hungrier could buy ham sandwiches. They could eat hot dogs, too, they just couldn’t ask for one — the phrase hot dog actually came later, in 1905, than the ability to buy and eat one at Palace of the Fans.

For the 3,000 others seated in the six rows of folding chairs, or the wooden benches behind it, in the grandstand, or the 4,000 standing room only fans in the outfield, some standing directly behind the outfield fence, other vendors walked among them all game long, selling candy, pretzels, lemonade and beer.

Ten thousand people came through the turnstiles that Thursday afternoon in 1902, making for a happy Brush — who loved baseball but loved making money at least as much. This was a Reds team that had finished 52-86 the season before, and attendance more than doubled from their 1901 season-opening crowd of 4,900.

Under a headline reading “Enthusiasm”, this is the lede in the Cincinnati Enquirer on April 18, 1902: “Unless the early returns are followed by an unprecedented slump it may safely be said that the National League has not suffered any fatal wounds during the winter’s strife,” it read, referring to the battles between leagues that produced, ultimately, both the American League’s birth and ultimately, the World Series. “Not for years has there been an opening to compare with yesterday’s. Cincinnati has seen nothing like it for years.”

The paper also took special notice of the nature of the crowd, mixing and unified by their love of baseball. Under a different headline reading “Splendid Crowd, Made Up Of Representative Citizens of Cincinnati and Vicinity”, another sportswriter cataloged it this way: “The office boy rubbed elbows with the millionaire, who in turn discussed the fine points of the game with his next seat neighbor, a farmer who had reckoned with his unsuspecting wife that this would be a good day for him to take in a load of that timothy hay…” The farmer in question, having gotten his chores done early, then “wandered out to the grounds to see what kind of a ball team McPhee had this year.”

The farmer and the millionaire and the office boy, provided they were all rooting for the home team, went home disappointed in the result, a 6-1 loss. The 1902 Reds ultimately finished at 70-70, going through three managers in the process, and finishing fourth in the National League, 33.5 games behind Honus Wagner and Jack Chesbro’s powerful Pittsburgh Pirates.

But the biggest loss of the season, for Palace of the Fans purposes, came in August when Brush sold his Cincinnati Reds interest to a syndicate led by Ohio political boss George B. Cox and August Herrmann, who was the de facto commissioner of baseball for much of the subsequent two decades.

Over the next few years, other franchises determined that the permanent, concrete structure in Cincinnati made a great deal of sense. By the end of the decade, Forbes Field opened in Pittsburgh for the Pirates, Comiskey Park in Chicago for the White Sox. Shortly thereafter, Wrigley and Fenway followed, and with different ownership groups in place, we might still have Palace of the Fans, too.

After all, the reasons for Palace of the Fans to be destroyed weren’t insoluble. The stadium experienced some cracks in the concrete, the kind of thing an owner more interested in building anew might use as an excuse to do so. So, too, was the fire that destroyed a significant portion of the stands.

The seating area was too small, but this was precisely the case at Wrigley, too — 14,000 at the park’s open in 1914, but 38,396 by 1927. Building additional seating around the infield and outfield was entirely necessary, and furthermore, possible at the very same site. We know that because the ballpark built to replace Palace of the Fans, Crosley Field, was situated at the exact same site, Findlay and McLean. It held 20,696 on Opening Day, 1912, and expanded to nearly 30,000 by 1970.

But the biggest factor leading to the demise of Palace of the Fans? The owner of the Reds was no longer the man who’d wandered, eyes wide, through the Chicago World’s Fair and imagined a ballpark to rival it.

That man now owned the New York Giants — in typical Brush fashion, he sold the Reds for $150,000, then bought the Giants for $100,000, thus both realizing his dream and turning a tidy profit in the process — and he faced a similar problem with his even-older ballpark, the Polo Grounds, which suffered a devastating fire in April of 1911. So we don’t have to wonder what Brush would have been predisposed to do in such a scenario — even though the Polo Grounds hadn’t been his brainchild, Brush quickly moved to rebuild the Polo Grounds “on lines conforming with the general character” of the ballpark as it had stood. Most of the wooden grandstand was preserved.

It takes significant historical mental gymnastics to envision Palace of the Fans as still standing today, without question. It would mean some combination of Brush remaining owner in Cincinnati through the fire, a growing public appreciation of the stadium that allowed it to avoid the late 1960s-early 1970s fate of Crosley Field and its brethren, like Forbes Field and Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia, growing into the historical landmark status. Those that remained, like the temples of baseball that were tragically destroyed, are all here as a result of such accidents, though. It’s hard not to think about what history might have been made at the grounds, even if it had been given a lifespan the length of the Polo Grounds. What right field catch would be the Cincinnati equivalent, with a wall 450 feet away in right, of Willie Mays’ 1954 World Series grab in straightaway center off the bat of Vic Wertz? What would Palace of the Fans have done to the power numbers of Ernie Lombardi? Would Ted Kluszewski have given up pulling the ball entirely?

As for that public appreciation: it feels not only plausible but likely, given how much of it exists for a ballpark that lasted a decade and hasn’t been seen for over a century. A thread through history of all those who have experienced Palace of the Fans either virtually, or in person, is an understanding that what existed, for just a decade, was the single greatest monument to the game.

The sportswriter Al Spink wrote in the Reno Gazette-Journal (and doubtlessly other papers, syndicated across the country) on Dec. 30, 1918, almost as an aside about Brush: “It was he who revolutionized all ideas of baseball stands in the United States by building, years ago, the stand in Cincinnati, which was called ‘The Palace of the Fans.’ In its day, it was the finest baseball structure, although not the largest, on the circuits of the major leagues.”

Seventy-five years later, Cincinnati Enquirer columnist John Eckberg wrote an ode to the Palace of the Fans, urging the Reds to build another park just like it, as Crosley Field’s successor, Riverfront Stadium, prepared to give way to the team’s current home, Great American Ballpark. The Reds didn’t — at least not in full ballpark form — but it is worth noting that the entrance to the team’s Hall of Fame was not modeled after Crosley Field, the team’s longest-standing home, nor Riverfront, which hosted the finest Cincinnati Reds teams of all time, The Big Red Machine of Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan and Pete Rose. The lobby is built to replicate the Cincinnati facade, and the surroundings, of what it felt like to enter Palace of the Fans back on April 17, 1902.

“Bring back the Corinthian pillars,” Eckberg wrote on Dec. 5, 1993, 100 years after Brush first saw his vision at the World’s Fair. “Bring back the pizzazz. Bring back the Palace.”

It is a call through the ages, and it continues to this day.

All photos in this piece were sourced from Digitalballparks.com. In addition to the articles cited here, Newspapers.com archives of the Cincinnati Enquirer from April 18, 1902, April 1, 1996 and September 16, 2004, along with the Buffalo Courier from August 11, 1902 were utilized in researching this story.