Beau Kittredge devoted his life to ultimate frisbee, becoming the undisputed best in a sport that can hardly pay a livable wage to “professional” players.

Beau Kittredge understands Tom Brady. To be part of a historically successful program and to leave, part of you wanting the decade of winning to be a little more about the individual and a little less about the collective.

“With Tom Brady and the Patriots, I can know exactly why he wanted to go. That’s the way I felt on Revolver. Everyone was like, ‘oh, it’s the Revolver program that’s good,’” said Kittredge to FanSided in a lengthy pandemic Zoom interview. “Okay, well, then I’m going to go somewhere else and we’ll see how good this Revolver program is.”

Then to win elsewhere, in Kittredge’s case, beating the very dynasty he built — not even Brady got to beat the Patriots in the Super Bowl. Kittredge understands Brady in a visceral way that few athletes in this world could. But Tom Brady could never understand what it is to be Beau Kittredge.

Kittredge is the greatest ultimate frisbee player of all time. To understand what makes Kittredge unique — to understand the significance of the mythical San Francisco Revolver — we need to zoom out and first learn about the relatively new sport of ultimate frisbee.

The sport is played with seven on the field for each team. The offense passes a disc between players, who can’t run with it after catching, and in that way, work to eventually catch it in the end zone. If the disc hits the ground, lands out of bounds, or is intercepted, then the defense gets a try to reach the other end zone themselves. And for two decades, whichever side has featured Kittredge has had a pretty good chance of reaching the end zone itself.

Perhaps because the sport was invented only 52 years ago, the ultimate world remains divided. College ultimate is the largest division of USA Ultimate (USAU), but the most decorated division is club, wherein some of the winningest programs in the men’s, women’s, and mixed divisions have existed for decades and have long institutional memories, mythologies and legacies.

Many of the best college programs exist as feeder systems into the top club teams of their regions, such as the University of Colorado feeding into Denver Johnny Bravo. Still, even the biggest club tournaments are held on small fields where fan seating on bleachers isn’t a real consideration. Because games only require uniforms, football cleats and a few plastic discs, the few sponsors that exist are usually ultimate-specific apparel companies. The final games of tournaments always have crowds, but the majority of viewers are parents of the players and the vanquished rosters of all the teams who didn’t reach the championship games.

At the same time, multiple attempts at semi-professional leagues, both men’s and women’s, have stormed into the ultimate world. The largest and most popular is, by far, the American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL), which is controversial in the world of ultimate because it changed the sport. The AUDL introduced referees — violating one of the original pillars of the game, self-officiation. Games are played on football fields, which are far larger than traditional ultimate field sizes. They made that choice specifically because using only half of football fields would look strange on television; the AUDL has different goals, and a different intended audience, from USAU tournaments. Unlike no-frills USAU games, many AUDL teams play in stadiums with announcers and halftime shows, and they appeal to fans who neither play ultimate nor are related to ultimate players. But when Kittredge entered the world of ultimate, the AUDL wasn’t even an idea, and even the best players had to buy their own plane tickets to tournaments like everyone else.

https://twitter.com/theAUDL/status/1361729361649532932

Born in an Alaskan bush village of a few dozen, Beau Kittredge was raised in Anchorage and introduced to the sport playing pickup. At 6-foot-4 with a 36-inch vertical and a 40-meter time under 4.4 seconds, he looked and moved more like an NFL wide receiver than a frisbee player. But it was luck that brought him to the college level. After high school, he found himself in Boulder for a weekend and decided to play in a tournament. Fellow participants who were college players from the University of Colorado were wowed to such an extent that they did something unprecedented.

After hearing the stories about Kittredge, alumni ultimate players from the university pooled money together to offer Kittredge a makeshift scholarship if he played ultimate for the school. It may not have been a legitimate scholarship, but it was as close as ultimate was going to get in 2004. Ultimate is a club sport and does not participate under the umbrella of the NCAA, but with almost 1,000 teams across multiple divisions, there’s no shortage of competition. Through his strange scholarship, Kittredge was already making the sport more professional via his entrance to university, albeit in the ramshackle way that ultimate functions.

Playing for the Colorado Mamabird, Kittredge accomplished two significant feats for the sport. Of course, he won a championship — that became commonplace for him over the course of his career. Perhaps more importantly, he jumped over a guy.

Kittredge’s athleticism revolutionized the sport of ultimate. He did things that no one had before conceived as a frisbee player. The highlight, in its own way, changed the sport. Current ultimate star Antoine Davis — who later became a teammate of Kittredge — says that seeing Kittredge’s highlight college play convinced him that the sport contained real athletes. That was no mistake; other athletes seeing frisbee as legitimate has always been one of Kittredge’s goals.

“I wanted to make ultimate a real sport and be viewed by people that it has real athletes,” says Kittredge. “I mean, that was our goal in college — let’s make people, when they talk about ultimate, they talk about it as a thing that has real athletes. I want to just be able to take on any other athlete in any other sport. If another athlete came into the sport, and tried to dominate, I wanted to show them that they weren’t going to be able to, that the sport already had athletes.”

Kittredge joined the club team Denver Johnny Bravo after college, and they reached the USAU club finals in 2007, though they lost. Kittredge learned that at the highest level of the sport, he couldn’t do it all alone. He has long been an unconventional leader — often distancing himself from his teammates at halftime rather than giving chest-pounding speeches — but he learned that trust has to be reciprocal. In 2009, he and close friend Martin Cochrane moved to San Francisco. Cochrane had a job that required his relocation, but Kittredge can’t remember his own job at the time — he thinks he worked in a shoe store; the move, for him, was for ultimate purposes alone. Club players actually pay money — for uniforms, tournament dues and travel expenses — rather than earn it from the season.

The two of them joined a then-unheralded club program named San Francisco Revolver. It was at the time the second-best ultimate team in the Bay Area, but Kittredge set about doing what he did best and professionalizing. He and his teammates continued the “ludicrous” amount of training Kittredge pioneered in college, including at times two-a-day workouts six days a week. Ultimate, to them, was the type of sport that real athletes played. So they set about realizing themselves as athletes.

It’s fair to ask why Kittredge played ultimate frisbee. He hasn’t earned a livable wage playing for the majority of his career. He hasn’t earned the recognition or fame that even lower-league players garner in established sports, like the Canadian Football League or any of the variety of European basketball leagues. With his athleticism, Kittredge could have made more money playing practically any other sport under the sun. Yet he’s dedicated his life to being the greatest ultimate player of all time.

Why?

“I do often wonder what it would have been like (if I’d played other sports),” mused Kittredge after a pause. “I mean, the thing is, you have to love something to be able to commit as much (time) as really good NBA players and good NFL players. And I don’t know if I did, I just don’t think I loved them as much as ultimate. There’s something about the way the sport is played. It had a more open field to it, as far as like, maybe I can be myself more in ultimate than in any other sport. I think because other sports are defined already. And the roles, and everything else was created, and even the direction of what the sport was, and how it was played.

“Ultimate was like an open canvas where it was not really defined, and I could paint whatever picture I wanted to. I like creating, and ultimate gave me the most creative freedom to shape it and make it my own.”

In the process of Kittredge defining the sport, Revolver became a dynasty. They won five USAU championships in nine years. Kittredge and his teammates, many of whom were superstars in their own rights, formed much of the roster representing the United States in international men’s competition, where they won international golds in 2012 and 2016. There had been previous dynasties in the world of ultimate — New York, New York, Death or Glory, Furious George — but Kittredge and Revolver hewed their place among the best.

The AUDL was founded in 2012. When the league added a West Division in 2014, Kittredge and many of his Revolver teammates joined the San Jose Spiders. They won back-to-back championships in their first two years in the league as Kittredge won consecutive league MVP awards. His combination of size, powerful acceleration and vertical explosion meant his team always had a weapon superior to any other: when the going gets tight, just throw the disc as far as you can. Kittredge would come up with it.

Beau Kittredge has helped carry ultimate frisbee towards professionalization

In 2016, the Dallas Roughnecks joined the AUDL, and owner Jim Gerencser decided to create a superteam. His first call — in fact even before the team was officially created — was to Kittredge. He offered Kittredge a job with his company, Nationwide Auto Services, that had a “pretty easy day-to-day” and allowed Kittredge to focus on his frisbee career. The Roughnecks signed some of ultimate’s other superstars, including some of Kittredge’s best teammates and longtime Kittredge rival Kurt Gibson. The Roughnecks came as close to professionalizing the sport as any other team, and part of the job was that Kittredge had to do his part to grow the sport. He and his teammates filmed advertisements, chased sponsors and sought media opportunities at every turn. They hustled to make the Roughnecks a household name. Unfortunately, they didn’t have any proper on-field competition in 2016. The roster was practically the national team men’s roster, and they ran the table on the league that season, winning even their playoff games by wide margins.

After a highlight year in Dallas, Kittredge returned to the west coast. He was unhappy so few players earned a liveable wage, and he didn’t want his individual success to be set in such stark contrast to many of his teammates. Still, he won another AUDL championship with the San Francisco Flamethrowers. Some of his Revolver teammates, such as Cassidy Rasmussen, remained his teammates on his AUDL teams, from San Jose to Dallas to San Francisco. Kittredge and his Revolver teammates understood each other and often lived together. While new teammates of Kittredge sometimes thought he was distant or even testing them with his understated leadership style, Kittredge’s long-time teammates knew he was just a fierce introvert. They knew he trusted them. At that point, already in his 30s, Kittredge had suffered and returned from a variety of knee injuries. He always came back slightly less athletic — but still always the most dominant when it counted. In the 2017 AUDL season, he caught more goals in three playoff games than in eight regular-season games.

During all that, Beau Kittredge and Revolver kept winning. While the semi-pro game brought salaries and fans, six-figure TV deals and sponsors to the sport of ultimate, the USAU club division remains more prestigious. The AUDL has grown massively. There are 22 teams across the United States and Canada. The league has signed landmark television and sports betting deals. Games, particularly in hubs like Madison or Montreal, can sometimes host a few thousand fans. The AUDL has a significantly larger presence in the non-ultimate world, but the USAU remains the pinnacle within the ultimate world itself. It has a longer history and more weight attached to its titles. While the Spiders and Roughnecks and other teams for whom Kittredge has played were fun dalliances, Revolver remained his dedicated partner. He always remained committed to Revolver in USAU competition.

And then he left.

Beau Kittredge’s departure from Revolver was shocking to the ultimate world. Not even his teammates knew he was leaving until his announcement.

“I tried writing Revolver a letter many times but kept deleting it, and in the most cowardly way possible, this is how they are going to find out that it’s over,” he wrote at the time of his decision to leave.

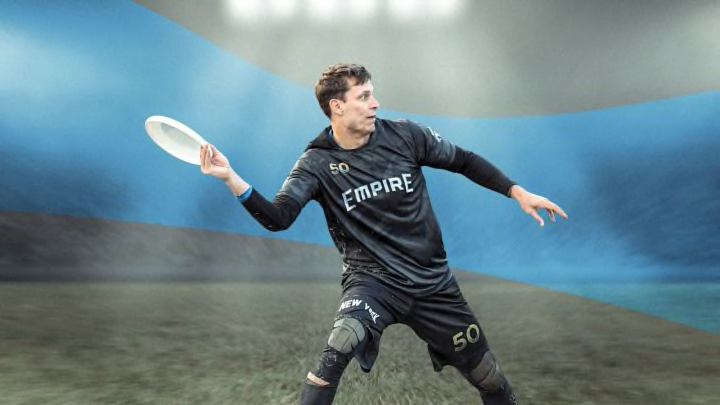

Kittredge moved to New York, joining the club team Pride of New York (PoNY) and the AUDL team Empire. He did it for a variety of reasons, both ultimate and non-ultimate. He wrote about it afterward, but there was another reason he left that he didn’t mention then: he had only won club championships with Revolver, and he wanted to prove he could do it elsewhere. It only took two years for him to win a USAU and an AUDL championship in New York with PoNY and the Empire respectively — the first in both franchises’ existence.

In 2018, PoNY went to the club championships, which is the pinnacle of the USAU season. They came into the tournament as a strong contender with a variety of stars, though Revolver’s talent level seemed to dwarf all others. By that point, Kittredge was a workhorse and a grinder; a variety of injuries had sapped his former dominance, but he remained a defensive presence and a consummate winner.

PoNY and Revolver both dominated the tournament, setting up the fated Beau Kittredge-bowl in the finals. Though Revolver was undefeated to that point in the tournament, PoNY humbled them, winning 15-7. The final goal was scored by New York’s defense. They forced a turnover near San Francisco’s end zone, and Kittredge immediately bolted to the end zone. He caught the final goal of the tournament.

He told me later he created an entire defensive game plan for PoNY to use against his former team, but never shared it with his new team. They didn’t ask, and he didn’t want to be overbearing. (Also, PoNY’s coaching staff, led by one of the best coaches in the game in Bryan Jones, crafted a very similar game plan completely separately, which meant Kittredge was comfortable not asserting himself to the foreground of the team.)

As he collapsed to the field at the end of the game, I grabbed Kittredge for a moment before the ESPN cameras swooped in. I was covering the tournament at the time for USAU, and I had a prior relationship with Kittredge. He told me he wanted to be the one to score the final goal against his old team — his only goal of the tournament. Not even Tom Brady got to do that.

“I was very tired,” said Kittredge then, “and I didn’t really want to cut. I figured if there was going to be a story or something, that it would make a better ending.”

Fast forward to 2021, to our pandemic Zoom interview, and Kittredge is less tired but more muted. He’s demure, remembering the highs and lows (mostly highs) of his career. Between college, club, international, and semi-pro, he doesn’t know how many championships he’s won. (He’s won 17, all told.) He doesn’t know where all the medals are.

“Maybe they are here (in New York),” he said. “Maybe some are in Alaska. That kind of stuff doesn’t really interest me too much, maybe someday it will.”

But his career, as he knows it, is for all intents and purposes over. He won’t commit to retirement during our call, but it beckons to him.

“If I was to play ultimate again,” he said, “I would need to put a lot of work into making sure that my body and my mind and my skills were up to where I would be comfortable stepping on the field. And I think that right now, that amount of time and energy is just way too much.”

His time playing the sport feels complete; his championship-winning goal over his former championship-winning club was a bookend to the greatest ultimate career of all time. His body has been ruined from various knee, shoulder, back and ankle injuries. Paradoxically, the pandemic has allowed him to heal and rest — something he hasn’t had an opportunity to do for almost two decades. When he works out now, he no longer has to “crawl around on the floor” after.

But Kittredge is no longer working out to play ultimate. His life is broader than the game. During the pandemic, he started training to run an Ironman because “it seems like it’s the hardest thing that I could possibly do.” He’s making a video game, which he’s been doing for several years. It’s on the fifth iteration, and he says that he loves the creation process “as much as he loves ultimate.”

That could say as much about his current relationship with ultimate as it does everything else now that ultimate is more or less in his rearview. His fame in the ultimate world is immortalized, recognized and lauded at every tournament he attends. That doesn’t mean he’s on perfect terms with the sport.

“I don’t really particularly care about fame that much. But money is a very important thing that would be wonderful to have and make life a lot easier,” he said.

He never achieved his goal of making ultimate a relevant professional sport. For all his hustling out of garages, chasing sponsors and mainstream attention, ultimate has made strides but remains unable to pay its best players liveable wages. He never signed the Nike contract that he so craved. He wanted to be like Michael Jordan, and he was, but without any of the trappings. Kittredge has given his life to the sport of ultimate, and it has given him the soupy field of Passchendaele for knees and a lost box or two (or more) full of medals and awards.

Is that a fair trade?

“How do you balance what you’re getting out of what you’re putting in? And is it worth it?” he mused.

“You might only get one shot at life, so you might as well try to go down whatever path is going to give you the most joy and ultimate gave me a lot of joy versus trying any of the other sports that were more concrete.”

He loves the sport, even if he describes his current relationship with it as “open.” It’s defined him for decades, and so too has he defined it. As much as he can be frustrated with the lack of reciprocation of value, ultimate for a long time was a foundational source of joy in his life. That’s enough, even if it’s not everything it should be. That doesn’t mean Kittredge has succeeded in every goal he’s had.

As Beau Kittredge leaves the sport, it looks much like it did when he entered it, at least structurally. Though there is a semi-professional men’s league, few players earn salaries beyond a per-game stipend. The opportunities that do exist are dominated by men; the ultimate world is currently riven by a gender equity battle, with Kittredge often on the receiving end of criticism because of his relationship with the AUDL, which is more or less a men’s league. Amateur club ultimate remains the pinnacle of the sport, and the best club players still pay to play, limiting access to those of relative affluence. The sport as a result remains overwhelmingly white.

But on the field, the players do look more like real athletes now. Through his hustle on and off the field, Kittredge has helped the sport look like other sports and helped frisbee players look more like other athletes. He has changed the sport forever. But it has gone too slowly. A superstar entering the sport today has much the same prospects as a superstar entering the sport 20 years ago — both would need to work at a shoe store, or as a children’s author, or in a video game studio, as Kittredge did and does, to support a sport that is ultimately still a hobby. Kittredge’s ability to fight that battle on the field is over. It’s about the only mountain he hasn’t summited in the ultimate world.

Millions play frisbee around the world. The best ones still need another job. Kittredge spent much of his career trying to make sure the greats who came after him wouldn’t face that problem. They still do.

Beau Kittredge is turning 39 this month. He could still contribute to a winning ultimate team, if not as a star then as a defensive role player, but it’s not worth the toll it would take on his body. Brady and LeBron James — both of whom are heroes of Kittredge — and other athletes who still win so late in their careers have teams of staff helping their bodies recuperate. Kittredge does not.

There’s a small handful of athletes who have ever achieved both the level of success and the longevity of success that Kittredge has. Brady, James, Roger Federer, Serena Williams, Kareem-Abdul Jabbar, among others. Kittredge has much in common with those athletes. But if he has indeed retired from ultimate, he’ll still need to work for the rest of his life to live, just as he has during his ultimate career. That makes him the same as the vast majority of the people in the world, but it’s unique for an athlete that has reached his level of success.

He’s won everything there is to win in ultimate, but he’s failed in his greater goals of making sure the next Kittredge won’t have to work in a shoe store while simultaneously being the greatest player on earth. Yes, Kittredge understands James and Williams and Brady in ways the rest of us cannot. But they could never understand what it is to be Beau Kittredge.