Journalists Frankie de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo, and Semi-Pro Hall of Fame linebacker Holly Custis, discuss women’s football as a safe queer space.

Heterosexual men have fought to keep football reserved for men, justifying gendered exclusion with everything from quack medical theories about female anatomy to a sneaky clause in Title IX that still prevents young girls from playing the game.

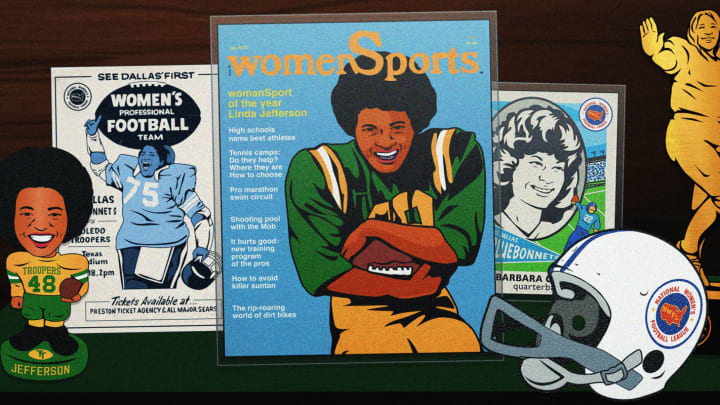

But being told “no” didn’t stop men from organizing and supporting women’s teams in the 1970s, and it didn’t stop women from playing. Intentional or not, the women who embraced football committed a revolutionary act, one that defied gender expectations against the supposed epitome of American masculinity.

“Hail Mary” authors contextualize queerness in the NWFL era

For queer women, revolution was nothing new. Neither was gathering and organizing in safe spaces. Perhaps this is why the NWFL’s Dallas Bluebonnets became a natural extension of the Dallas lesbian bar scene, where women met and drank and flirted. Playing football, they tackled, brutalized, and sprinted, all of which grated against heterosexual feminine expectation. According to “Hail Mary,” an exhaustive account of the NWFL era, when the Bluebonnets manager once asked his players to wear dresses, they laughed him out of their locker room.

But these gridiron pioneers did live in a dangerous time, one in which cops cracked down on queer individuals. “Hail Mary” authors Frankie de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo recant how the Dallas lesbian bar scene in the 1970s became ground zero for professional women’s football in the area. In Chapter 6 of their book, “Dallas Enters The Fold,” de la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo delve into first-person accounts from queer women who played football during the 1970s, weaving them into the story of how the Bluebonnets began in Dallas.

Speaking with FanSided, Frankie de la Cretaz shared what football meant for queer women in Dallas and throughout the nation.

"“I think that Lyndsey and I, we knew that some of the women were probably queer, because people are queer. I think the question for us was whether or not they would want to talk about it, and specifically, whether they saw it as connected to their time in this league, and many of them really did. And I think that’s because, as you mentioned, there were lesbian bars at the time, there were a lot more gay bars. And that’s because, in the 1970s, it still really was not safe to be openly queer.And so a lot of the women who tried out for these teams and, as we detail in the chapter about the Dallas Bluebonnets, the women who were on that team in particular, many of them knew each other from the lesbian scene in Dallas, and they met in those bars. They organized other sports leagues out of those bars. And so you know, people who are marginalized are really good at creating safe spaces and a hostile world and so these teams, for the gay players, were an extension of those bars, and were safe spaces where they could be openly who they were.”"

But the fact that many of the Bluebonnets were queer presented a complex reality — it was, as the authors describe, “both important and unimportant.”

"“The fact that they were gay was both important and unimportant to the queer women on the Bluebonnets. They were there first and foremost to play football. That so many of their friends were there, too, and their sheer number — in addition to the way sports teams can often feel like families — combined to make the Bluebonnets a place where any woman, gay or straight, could be herself.” [Hail Mary, p. 82-83]"

The emphasis on community is critical to the women’s game, even to this day. With much of the world either oblivious, opposed or uninterested in what they do, women banded together with their teammates. The word “family” frequently comes up when past and present players describe their team environment. Queer women were fundamental to creating that safe space that gave people of every gender and orientation the freedom to do what they loved: playing what many considered to be a game for men.

Holly Custis: Women’s football teaches men how to support queer players

Even though the NWFL dispersed in the late 1980s, the community that the game has created for queer women never went away. To this day, women’s football is synonymous not only with acceptance, but an embrace of women and queer folk who vary in race, size, class, religion, and every identity one could imagine.

In her 16 years playing professional women’s football, Semi-Pro Hall of Fame linebacker Holly Custis spoke to FanSided about what women’s football has meant to her as a queer woman.

"“I think it’s been kind of a safe space.And I think, on a fundamental level, you need every body type in football, right? Another thing I noticed about women’s football is that bigger men are taught that it’s okay to be big because we need your size. Bigger women are not taught that. So I have noticed that football has given bigger women an outlet they haven’t really had before, and that’s beautiful.The other side that we’re talking about with queer women: yeah, I think having that safe space to be who you are is important in anything in life. And I think football, naturally, because of the connections you make, it does become a community or like a family. And because it’s a safer space, you do find people learning about themselves and learning about other people in a really healthy environment, I think, because nobody is going to judge you for being gay or straight or bi or whatever you are. Doesn’t really matter as long as you’re on my team, and we’re blocking the same direction and we’re coming together to make it tackle. I don’t really care as long as you’re my teammate, right?And I think men’s football could actually learn from women’s football in that area. And they’re starting to — it’s a little slower — that it really doesn’t matter, right? As long as you can play together, and your intent is to be the best football player that you can be, it doesn’t really matter who somebody likes or doesn’t like.I think having that safe space, for queer women in particular, has been extremely helpful. I’ve heard a lot of stories of people that when they come to football, maybe they’re a little younger, and maybe they’re first starting to come out a little bit, and maybe their family isn’t as supportive, and now they have a community that is supportive, and how important it is emotionally and psychologically to them to be like, ‘Hey, I’m gonna be okay.’ Because there are other people like me that understand, or even people that aren’t like me — just nice, empathetic people.”"

Custis expects to retire from professional football soon, but she has been a pillar of the women’s game throughout the Millennium. In all that has changed, and all that hasn’t, one constant has remained the same: women’s football has created integral community for queer folk across generations, something that the men’s game could certainly embrace.

To learn more about the history of women’s football and explore the rise and fall of the NWFL, read “Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League” by de la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo.

Custis, who comments on the past and present of the game from a player’s perspective, blogs under the Relentless21 moniker on WordPress and YouTube. Custis is also a co-host on the Gridiron Beauties podcast.