The 2022 World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon made sustainability a core principle. But can any large-scale, international event be truly green?

This year, for the first time in history, the track and field World Athletics Championships are being held on U.S. soil. Unsurprisingly, the meet is being held in Eugene, Oregon, commonly referred to as TrackTown, USA.

Entering Eugene is like stepping into two, merged worlds. Walk through its main streets and meet the whimsy of a Pacific Northwest, liberal college town — all Nalgene bottles and mildly expensive, fast-casual restaurants. At the same time, the city is scattered with imagery that evokes the long tradition of great athletes who have passed through: a shrine to the late distance running legend, Steve Prefontaine at the site of his death; a mural of the decathlon World Record holder, Ashton Eaton on the side of a popular pizza joint; and a giant tower in the shape of the Olympic torch overlooking the track. The center of it all is Hayward Field, the state-of-the-art stadium, which just reopened last year after a $270 million renovation, nearly entirely funded by Nike co-founder, Phil Knight. Hayward will be the site of the upcoming World Athletics Championships.

Eugene has long been considered the center of track and field in America, but the reputation wasn’t earned accidentally. Here, Knight founded Nike; the legendary track coach, Bill Bowerman ignited the jogging fad that swept the country; and perhaps the closest figure the sport has had to a mainstream pop culture icon, Prefontaine, lived here until his tragic death at age 24. The legacy has been preserved, on some level, by the many professional athletes who live here and share the city’s tracks and trails with less accomplished runners who also live here — and live to attend track meets at Hayward Field. This city is full of fans.

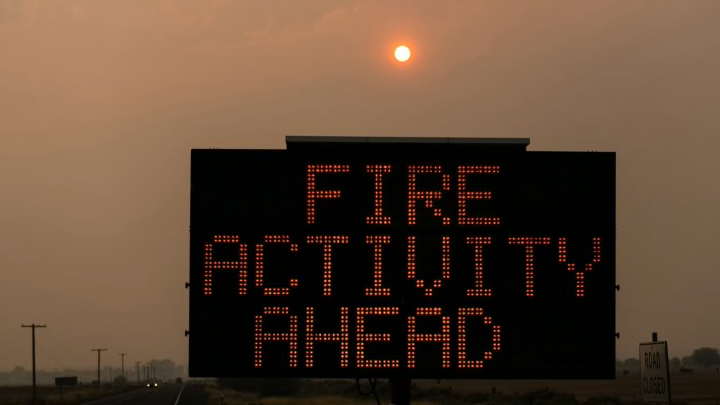

And yet, over the past few years, Eugene has become an increasingly hostile place to live and train. In the fall of 2020, the forests surrounding the city were ravaged by some of the most devastating wildfires in Oregon’s history. When the Air Quality Index (AQI) exceeded 500 for over a week, people couldn’t step outside without expecting severe lung stress. Smoke invaded the many homes and apartments that lacked sophisticated air filtration systems. As the sky turned red, many couldn’t escape town.

For decades, Eugene has had a reputation as the perfect training location for distance runners. The winters are mild. The summers are mild. There are trails everywhere and lots of people to share them with. But the 2020 wildfires presented unprecedented challenges for the athletes who live here. Training for long-distance events is a delicate act: You have to run enough to get better but not stress your body so much that you get injured or sick.

“I was very worried about my health. I didn’t want to run through the ash even if it was better than other days,” says Carmela Cardama Baez, the NCAA 10,000-meter champion in 2021, who lived through the fires. “I didn’t want to deal with any long-term health effects that I didn’t understand. I was very anxious about what to do.”

Many days she’d drive an hour-and-a-half to the Oregon coast for a lower AQI to log an hour of running. Some days she’d run inside on the treadmill, but even the University of Oregon’s incredible indoor facilities had been invaded by the poor air quality.

Less than a year after the fires, the U.S. Olympic Trials were held in Eugene. June of 2021 recorded a string of the hottest days in Oregon’s history. The final day of the Olympic Trials reached 111 degrees, and the real feeling on the track was over 120. Some athletes’ events were 12-and-a-half laps around the track that day. Others competed in up to five events in a single day. Taliyah Brooks is a former national champion in the heptathlon but that day couldn’t complete all seven of her events. She fainted from heat exhaustion and was carted off the track in a wheelchair. The spectators were told to evacuate the stadium.

Oregon22, the local organizing committee that is responsible for staging the World Athletics Championships, has made Oregon’s nature and environment central to their branding of the event. According to Jessi Gabriel, their communications director, Oregon22 has been very intentional with evoking imagery of Oregon’s forests and landscape in their branding. Their website even has a page titled, “The Beauty of Oregon showcased through the WCH Oregon22 brand.” Regarding the branding, Gabriel says, “It’s about place, philosophy, and feeling. We have to have something that resonates with a sense of place.”

And yet, some wonder: how can such messaging be upheld at a mega-sporting event? How can climate change considerations be met — when fans and athletes are flying from far corners of the world to Eugene, Oregon, a town that has already begun to face the wrath of climate change? We wonder, what environmental concerns is TrackTown facing while hosting the World Athletics Championships? And is it ready to meet these challenges?

Eugene, Oregon brings a unique perspective to the 2022 World Athletics Championships

In some ways, Eugene was prepared to host a large-scale event more sustainably than most cities.

“In Eugene, there’s a strong sense of waste reduction. There’s a strong contingency interested in urban farming and making your own compost pile with your kitchen food scraps. From the time kids are in elementary school, they practice these things, and learn about them at gardens, on-site at their schools. Then, they bring them home,” says Shelly Villalobos, the executive director of The Council for Responsible Sport, a nonprofit that aims to measure and manage the social and environmental impact of sporting events. Since 2007, the Council has certified over 170 events as “environmentally and socially responsible”— including the NCAA Final Four Basketball Championships and the Chicago Marathon.

Villalobos believes that Eugene is uniquely situated to host environmentally-conscious events. Eugene’s culture of environmentalism, Villalobos and her colleague Keith Peters explain, expands to sporting events, and specifically to Hayward Field. “We’ve had our deepest impact in Eugene,” says Peters, “largely because of Shelly.” Villalobos lives in Eugene and formerly worked for the city as the Sport and Sustainability Analyst. “The community values of the place really have to drive and institutionalize this kind of behavior,” says Peters.

In the summer of 2012, Hayward Field hosted the Olympic Track and Field Trials, which the Council certified as socially and environmentally responsible. This means, the Trials complied with at least 27 of 61 of the Council’s “best sustainability practices,” which span from resource management to equity considerations. Over the following decade, the Council worked with Hayward Field to certify basically every major track meet held in the stadium, according to Peters. The World Athletics Championships this summer will be no exception.

Peters underscored how the Oregon22 leadership has been willing to work with the Council since the event’s early planning stages. The result, ideally, will be a merging of local and global sustainability practices. During the 10-day event, Oregon22 is working with Eugene-based Bring Recycling to collect and process waste in a sustainable way. Oregon22 also said they’ve made guides for navigating the city’s public transit and posted them to their website. Additionally, they’ve said they’re working with the food and hospitality services to optimize their waste management strategy during the event.

But Cerianne Robertson, a mega-events scholar, thinks these types of interventions, most often, don’t go far enough. “For each [mega sporting] event, we’ve seen narratives of how the event itself is going to be ‘sustainable’ but also leave a green legacy,” Robertson says. “And without exception, from what I’ve seen, these promises are always overstated. They allow corporate sponsors to participate in something that appears sustainable, but that actually is contributing to harm.”

While partnering with Bring Recycling and advertising Eugene’s public transit may reduce some emissions, the amount is small when compared to the emissions released when an estimated 200,000 people travel to Eugene from over 200 nations. That’s the nature of a mega-event. Villalobos highlights how travel is a major source of emissions and mentions the potential for carbon offsets. Although, the effectiveness of carbon offsets is also very limited.

Roberton’s research has another dimension: Large sporting events have often affected the most vulnerable people in the host community. An influx of tourists can increase the effects of pollution in low-income neighborhoods; increased construction can displace long-time residents; increased demand for rental properties and hotels limits affordable housing; and increased security and policing disproportionately harm people of color.

For the 2016 Olympics in Rio, for example, a new stadium was built specifically for the event. That doesn’t have to happen for this year’s World Athletics Championships. But some of the other justice-related concerns remain. Many apartment buildings in Eugene allow month-to-month payments, and in some complexes, rent increased by about 50 percent just for the month of July, anticipating the city’s increased number of visitors (confirmed by residents of the complex).

The Airbnb market in Eugene and its surrounding cities this summer is also heavily influenced by outsiders. “Corporate owners of Airbnb spaces are renting out multiple places, or people are renting out second and third properties that they own, which contributes to those spaces not being available to actual long-term residents,” Roberton says. “So people are actually removing units from the market to convert them into Airbnb.”

On the contrary, Villalobos and Peters highlight how the city of Eugene is using the World Athletics Championship and other Track and Field events as reasons to strengthen Eugene’s environmental legacy, ideally benefiting all community members. Peters points out, “The city is investing in an old abandoned steam plant along the Willamette River and turning it into a park.”

The City has also installed 20 new murals and planted upwards of 2,021 sequoia trees ahead of the World Athletics Championships. “The city of Eugene is saying, ‘Let’s use this event as an anchor and the catalyst to invest in community programs that align with values of international cooperation and stewardship for the environment,” Peters says.

Although, some of Eugene’s sustainability projects are more dubious. The redevelopment project on the river includes plans to build a boutique hotel, for example, and one reason cited is that new buildings will help to house track fans. While some argue that this proposed hotel will build jobs and bolster Eugene’s economy, Robertson’s framework urges caution. Will this project increase prices in the area and push out folks who live nearby?

It’s like two different worlds exist in that part of the city: Last year’s demographic surveys indicate that roughly 3,000 unhoused people live in Eugene, and one of its largest camps is near the riverfront site. The city of Eugene will contribute $1.5 million toward the redevelopment project, and plans to help with the $5.2 million funding gap by requesting state assistance. Such an investment begs the question: What equity and/or sustainability projects is the city of Eugene, in turn, unable to invest in?

Combating climate change is riddled with contradictions. It may seem futile to invest in making change on a small scale — reducing waste at an event and encouraging fans to use public transit. Ultimately, a meaningful intervention to address climate change to the scale of its severity is a policy battle that must happen far above the heads of board members on the organizing committee of a nonprofit track meet. But change needs to happen on every level. And efforts at change must not leave behind the most vulnerable community members. Well-intended sustainability efforts from Oregon22 might be a good start for Track and Field — but they’re not entirely without consequence.

Emma Zimmerman is a freelance writer and journalist. Her work has appeared in Runner’s World, Trail Runner, Women’s Running, and Taproot Magazine. She is also the creator of the Social Sport Podcast, on endurance sports and social change. She lives, runs, and writes in Brooklyn, NY.

Matt Wisner is a writer and journalist who lives in Eugene, OR. His work has appeared in Runner’s World, Women’s Running, Input Magazine and more.