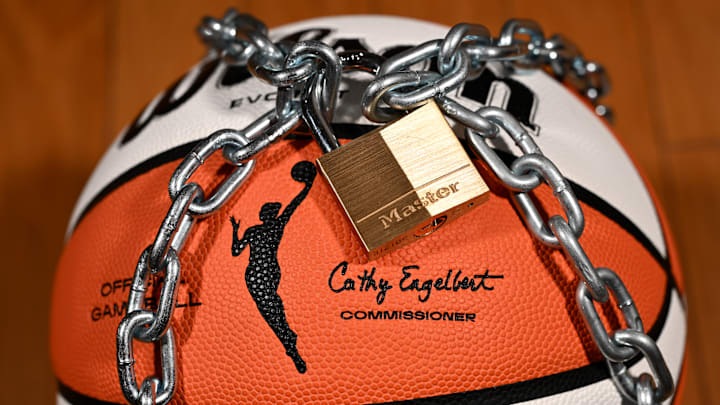

The CBA deadline set for this past Friday, Jan. 9, has come and gone with no deal. Negotiations will now enter a “status quo” period where the league is unable to implement any changes to pay, working conditions, or other benefits (housing, parental leave, etc) without negotiating first with the Player’s Association. In other words, both parties will continue to bargain in good faith.

Nonetheless, the league can initiate a lockout, or the players a strike, at any point moving forward. According to WNBPA vice president Breanna Stewart, a strike is something players are holding “in their back pocket” rather than initiating a strike in wake of the deadline.

Yet, WNBPA’s latest move suggests a strike may be sooner than anticipated. The organization has amassed a series of “Player Hubs” that will allow players to access courts, weight rooms, and recovery areas in the event of a work stoppage. Hub locations include facilities at Stanford University, UC Berkeley, UNLV, numerous Bay Club Network fitness centers on the West Coast, and WNBPA headquarters and numerous performance centers run by Exos Performance Lab on the East Coast. According to Sports Business Journal, players would also have access to a training space in Malaga, Spain.

WNBA Player hubs give the WNBPA big leverage in negotiations

Though WNBPA Player Hubs serve a very real function of allowing players to train continuously though a work stoppage, their sheer existence makes player solidarity credible before good faith negotiations break down. In other words, the Player Hubs transform the institutional solidarity demonstrated with the strike authorization into operational solidarity.

Strike authorization signaled solidarity in principle but did not guarantee solidarity in practice. In labor disputes, the central question typically becomes: which side can wait out the other? Often, management (the WNBA) outlasts labor (the players). Player Hubs change this. They make prolonged collective action sustainable for players from an athletic, social, and communal standpoint. They create spaces where rookies and veterans alike, across different offseason leagues and countries, can train for prolonged periods of time. This flattens out disparities like pay and access to resources that typically arise from differences in salary, age, and experience. In turn, if they choose to do so, the Hubs will allow players to sustain a longer strike.

Thus, though the Hubs may not seem central to player bargaining, they have already strengthened player leverage and, if necessary, will convert into long term bargaining power.

Arguably, operational solidarity is all the more important in a league like the WNBA where the average salary is much lower compared to professional men’s leagues like the NBA or the NFL. Male athletes have a much larger fiscal safety net, allowing them to strike for longer without additional structural support. For example, the longest MLB strike, which lasted from August 1994 to April 1995 led to the cancellation of 921 games, including the world series, and losses of $580 million for the league and $230 million for players. The potential WNBA strike would be the first in league history.

The WNBPA’s decision to put striking “in their back pocket” demonstrates strategic restraint: the addition of Player Hubs makes their back pocket a heavy one, adding substantial weight to the threat of a player-initiated stoppage. With the draft in April and the season start set for May, the ball is quite literally in the league’s court.