Most of the time, only four lanes are available for lap swim. Today I dip down, knee to concrete, and ask someone if I can share a lane with them. An older woman pops up and rips off her swim cap, revealing spiky white hair. She tells me, “It’s your lucky day! I’m done!” I smile and mark the lane with my water bottle, then walk over to the stairs to lower myself in.

Swimming etiquette is crucial in a place like this, though it’s often ignored. Teenagers will play in one end of the lane as I’m sprinting backstroke, creating the potential for a serious accident, even though I’m pretty slow. When I’m in a lane closer to the steps, men leave their flip-flops on my part of the ledge to access them on their way out so they don’t have to step barefoot onto the deck. Of course, I’ve had folks “forget” to ask before they slip themselves into my lane and swim right down the center.

It’s a bright Friday in July and the waters look pretty crowded. I try to do a mile twice a week over the summer when I have access to the lanes and the weather is good. I swim in Chicagoland at Centennial Beach — a limestone quarry converted and filled with a murky seafoam over 100 years ago. It’s not for everybody. As Mudrats on the swim team here, we filled a bucket with the slosh and threw it into the crystalline pools where our away meets were held, to the chagrin of club kids and their parents. We puffed out our chests each time we attempted this intimidation.

Centennial is classified as a “public beach” connected to no ocean. Sandwiched between a deep end of 15 feet and a shallow area that fans to zero depth is a proper Olympic-sized long-course swimming pool with eight, 50-meter lanes. It’s the sole place nearby where I can access that.

See the Centennial quarry, unlike a standard pool, is missing flags above the lanes, and the water isn’t clear enough to see through. In fact, I can’t see someone two feet from my face. On a sunny day like today, I can just make out the black shadow striping the painted white concrete bottom to trace my freestyle. The last five meters of solid red lane line is my only guide for how close I am to the wall when I’m on my back. My peripheral vision must be keen.

Why do I swim here? The long course is part of it. My flip turns aren’t the best and the cardiovascular high of 50 meter clips is heady. I also get to swim under sky and a crouching canopy of old-growth trees. The teal water against a cerulean dome is what might best be described as pure color.

As I take in my first hula hoop of breaststroke, I’m reminded that in this moment, I am an athlete. I am a huge fan of nearly everything competitive, but not combative — I watch baseball, basketball, and most Olympic sports, though I couldn’t compete in any of them. When I watch swimming, I learn from the athletes’ technique, their mindful comments post-race, and can actually apply some of it. This is true for me in no other physical pursuit. It takes me back to sitting on a towel as a tween and waiting for my race to start, stretching and watching the daredevil girls on the team chug Jolt while they shout to me their advice.

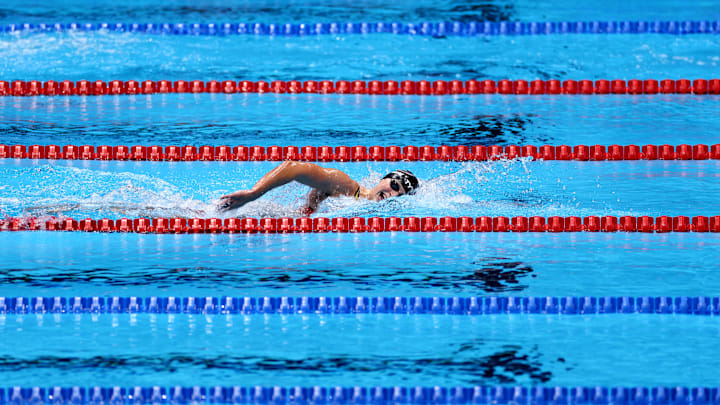

The swimmer I most identify with is Katie Ledecky. To be sure, I am not an elite athlete who routinely sets and breaks her own world records. My mile takes about four times as long to complete as Katie’s. I swim three or four different strokes to make up my distance, and she races only freestyle, with that signature loping stroke, breathing only to her right, on every single pass. But she is a miler, and so am I. We are working at the same pursuit. We swim the distance together.

Nearing 40 now, I am also a woman confronting chronic pain. For the last three years or so, almost no day has felt “normal.” I have damaged the tendons and bursa in my left shoulder and had hip labral tears surgically repaired almost two years ago. I still have pain in my lower back and hip flexor muscles. Daily stretches and physical therapy exercises allow me to pass as “normal,” but my joints are not healthy. I am hypermobile and on my best days, I am happy to show you my contortionist impression. In school, I bragged about my results on the “sit and reach” portion of the Presidential Physical Fitness Test, but I’m paying for it now.

It’s well advertised, but swimming does loosen the joints. The water cools my overworked muscles and tendons. I am weightless. As a kid, I always wanted to be an astronaut and exist in zero gravity; the next closest thing is wading into the water at any time and feeling the tension in my body vibrate out. My arms and legs unfold and are free. A few minutes of buoyancy and I feel less and less of what the ground does to me. I want to move, to imitate my idols in the pool. I fade into a siren.

Katie will participate in the Paris Summer Olympics in 2024, and she’s made her intention clear to swim at a home Games in L.A. in 2028. She’ll get there. She’s the woman to beat in the 1500 meters, owning the 16 fastest times ever in that event. She’s also practically undefeated in the 800, known to be her favorite distance. At 27 years old, she’s considered too old to be doing this at such a high level. Yet she routinely laps the field in the 1500 and manages to catch her breath before the second-place finisher touches the wall.

Why would she want to continue? There is nothing left for her to prove out at this stage — she’s the greatest female swimmer of all time and frankly, it’s not close. Training distance is notoriously difficult — swimming that much is hard on anyone’s body, even if it’s “good for the joints.” I know that if I don’t continue to hydrate and eat immediately after a long swim, I’m a goner, even at my novice level. Katie has to weight train and do recovery work as well, of course — not to mention her strict diet and schedule. But here may be a clue as to why we are still swimming: Anthony Nesty, Ledecky’s coach, says she “enjoys the distance.”

And to do it at that level, you have to love it. Even capable swimmers find training the 1500 meters incredibly boring. Alternatively, the rhythm of the repeatable strokes, falling into a groove, and timing up the wall could be termed meditative. When I stretch for that first pull of freestyle and my ribcage arches on the body roll, it’s a release into something. Katie has taught me to kick less, let my heels dance, and pace out my breathing, making each stroke my longest. It’s easier to keep my posture and use my core this way, something my physical therapists harp on.

According to Rowdy Gaines, longtime TV analyst for Olympic swimming and decorated U.S. swimmer in his own right, Katie “loves the pain” of the 1500. The gasping for breath, the burning lungs, the cramps in the legs. It’s certainly a test of exertion. I challenge any runner to do a few laps in the pool and force away the water’s wet cement — it’s different than wind shear. Swimming for an hour straight is the only way I can push my body to its cardiovascular limit safely. I don’t strive to come close to Ledecky’s times, but to incorporate her methods. Katie’s first 750 meters mirrors her back 750. In the 2023 1500-meter World Championship final, her splits were even. I’m training to pace myself and finish my miles strong.

One of Rowdy’s favorite phrases is “just find a lane.” What he means is that if a swimmer can make it through the preliminary heats and the semifinals to somehow make the final, they could potentially win. They are a threat because they fought their way into the race. Katie will find a lane wherever she wants one, and I can too. In this world, this lane is mine—the one place I own in this moment.

After every swim, I float face up for a few minutes to catch my breath on the wavy green carpet. It’s amazing how fast five minutes can go as I lazily cartwheel down and back, bobbing upwards. Coming from a lineage of backstrokers, I learned at a very young age how to float face up. Still, I remember being told as a 10-year-old that I needed to repeat the “Barracudas” level before I could move up in swim lessons. I joined the Mudrats instead. Watching the clouds moving east, the sun so intense behind them, I have to put my goggles back on.

When I rise out of the water and walk the winding steps up to the bathhouse, I trace this sky the whole way. In the quarry, nothing is limited. The sky is our ceiling, even in the showers. The feeling of being underwater will last with me for days, my balance a bit off and the waft of chlorine in my hair. I’m a sponge, waterlogged and washed out. I push and pull the humid air behind me on the mile walk home.

Fan Voices is a collection of personal essays highlighting the individual stories and experiences of fans and how relationships with sports, teams and athletes have rippled through their lives. Read more here.