At that moment — suspended between heaven and earth — his life was hanging in the balance. The ball had arced. He had risen to meet it. Gravity had been defied. When the ball nestled into the net, there might have been little surprise if Wayne Rooney had continued on his upward trajectory through the cool Manchester air, raptured away into the heavenly realms. His mortal frame instead plunged back to earth, foreshadowing another descent, as one of the brightest luminaries in football never quite hit the heights he reached that February afternoon at Old Trafford.

That this moment was so pregnant with meaning is hardly surprising. In many ways, the overhead kick exists at the boundary of the possible and the impossible in football. As the player finds themself almost entirely disorientated within the lines of the playing field, the seemingly improbable becomes feasible through a combination of supreme athleticism and extraordinary coordination. Reality is inverted at that moment and the footballer, hanging upturned in space like a transposed Jumpman logo, performs something of a minor miracle. Cristiano Ronaldo. Zlatan Ibrahimovic. Gareth Bale. Rivaldo. Dimitar Berbatov. Rooney himself. The litany of overhead kick artistes speaks to the sort of quality required for the skill’s execution.

The satisfaction of watching a great overhead kick is augmented by the sheer impudence of its architect in thinking it up in the first place. The questions pile up. What runs through a player’s mind? How do they settle on what is surely the most difficult course of action available to them? How do they process the calculations required to connect with the ball while fully upside down? How do they even have the confidence to take the shot in the first place?

These were the sorts of questions David Winner put to Rooney after the latter’s overhead kick proved the difference between Manchester United and their cross-city rivals in 2011. Rooney was all too happy to oblige.

“When a cross comes into a box,” the former England player explained, “there’s so many things that go through your mind in a split second, like five or six different things you can do with the ball. You’re asking yourself six questions in a split second. Maybe you’ve got time to bring it down on the chest and shoot, or you have to head it first-time. If the defender is there, you’ve obviously got to try and hit it first-time. If he’s farther back, you’ve got space to take a touch. You get the decision made. Then it’s obviously about the execution.”

Rooney presents his activities on the football pitch as the result of cognitive processes through which he weighs up the evidence and makes considered decisions in the milliseconds available to him. If this is right, the gap between elite footballers and the rest of us could be explained, in part, by a difference of intelligence: The better the player, the more effective their capacity to process information on the pitch. This efficiency is often articulated in terms of a slowing down of time. When listening to another one of Winner’s interviewees, Dennis Bergkamp, the former Ajax team manager David Endt was led to remark, “the seconds of the greats last longer than those of normal people.”

Even amateur players will have experienced the game in the way Endt and Rooney describe it. The journalist Jonathan Wilson has spoken of two of his own such experiences on the playing field: “On both occasions, once airborne, it felt as though I had hours to make decisions, that I could move stick or hand into the path of the ball as easily as if I were picking an apple off a supermarket shelf. This, I assume, is what proper sportspeople feel most of the time.” In Wilson’s version, as in Rooney and Endt’s, time seems to stretch out, and the player is able to weigh up the options — almost as if from a distinct vantage point — before acting in the requisite manner.

This account of a footballer’s thought processes is all well and good, except for the fact it turns out to be completely and utterly incorrect. As the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould has noted, “one of the most intriguing, and undeniable, properties of great athletic performance lies in the impossibility of regulating certain central skills by overt mental deliberation: the required action simply doesn’t grant sufficient time for the sequential processing of conscious decisions.” Or in English, footballers can’t possibly “think” on the pitch in the way Rooney claims to. They simply don’t have the time.

It appears, then, that the way we naturally talk about footballers’ on-field experiences is wrong. Our first question, then, is simple: Why?

~

Let’s start with some history.

Early in the 17th Century, Europe was hurtling headlong toward that period scholars would later dub the “Enlightenment.” Even at that time, however, with the continent still in the throes of medieval Christianity, the human being remained at the center of our understanding of the world. Man had been created by a loving God, and placed in a world that was transparent, immediately available and intrinsically meaningful to him.

By the end of the century, thanks to the work of thinkers as diverse as Rene Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton, things had changed. While all these thinkers (with the possible exception of Galileo) considered themselves squarely within the boundaries of Christian orthodoxy, they were responsible for a subtle adjustment in our understanding of the world. A move away from the prevailing view of the church, what Edward Casey has labelled an “early modern paradigm shift.”

Fundamental to this shift was Newton’s distinction, in the Principia Mathematica, between absolute space, which “in its own nature, without regard to anything external, remains always similar and immovable,” and relative space, “some movable dimension or measure of the absolute spaces; which our senses determine by its position to bodies.” The world was thus imbued with its own, “objective” order, independent of the human subject.

And so the central problem facing philosophers at the time became the source of the meaning we ascribe to the world. Following the publication of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in 1781, it became commonplace to view the human mind itself as the source of this meaning. The mind imposes categories on the world, through which otherwise formless stimuli were made sense of, ordered according to our own ideas and language.

What does any of this have to do with Wayne Rooney? Well, everything. Consider, again, his description of that overhead kick: “When a cross comes into a box, there’s so many things that go through your mind in a split second, like five or six different things you can do with the ball.” Rooney gives meaning to his experience, he applies ideas and language to the external world so that it might make sense to him. Almost 300 years after the fact, and the early modern paradigm shift continues to shape the way we talk about the game.

Our second question, then, is a little more complicated: Can we do anything about it?

~

In 1985, Benjamin Libet conducted an experiment which became fundamental to the scientific study of human consciousness. Using an oscilloscope as a timer, Libet measured the time between his subject’s first urge to press a button and the moment they actually pressed it. The average gap was 200 milliseconds. Meanwhile, measurements of the underlying brain activity suggested there were around 500 milliseconds between the brain “deciding” to act and the action taking place.

However you view the findings of Libet’s experiment (and questions have been raised about his methodology), one thing was clear: The time it takes a person to consciously process a task as simple as pressing a button is longer than that available to, say, a batter trying to hit a 100 mph fastball in baseball (413 milliseconds) or a male tennis player returning an average first serve (470 milliseconds). Rooney had more than 500 milliseconds to decide what to do with Nani’s cross against Manchester City, but not by much, and certainly not enough to think “five or six different things.”

But Libet’s findings do more than simply debunk the myth players think their way rationally around a football pitch. They also suggest that what we present to ourselves as conscious decisions are much less important than they actually are. Given there is a 300 millisecond gap between the brain initiating a response to an external stimulus and our becoming consciously aware of our decision to respond, any account of players engaging in what Gould called “overt mental deliberation” starts to look palpably naive.

This raises a more difficult question: If players aren’t consciously aware of the decisions they make on the pitch, in what way are they responsible for their actions? Or, as Wilson put it, “if it’s not Rooney, then who or what is it?” The possibility it is not a “who” at all is one Wilson seems to find mildly alarming: “It’s something behind the Cartesian cogito, perhaps analogous to Freud’s id, or the autre of Rimbaud, something primal and, frankly, rather disturbing given western society is based on the notion that the self has free will and is responsible for its actions.”

Of course Wilson acknowledges his own problem: By looking for something “behind” our actions, he remains tied to a Western idea of the self. He’s looking for something even more primordial than “the Kantian noumenal self” or “the Cartesian cogito,” but which follows the same sort of logic. Another, more basic decision-making actor. What Libet’s experiment makes clear, however, is that the thing “behind” the act is the human body itself.

This is where the real impact of Newton’s work comes to the fore. For by distinguishing us from the world in which we find ourselves, he succeeded in imposing on western thought a dualism between mind, the nub of a person’s conscious engagement with the world, and body, part of the objective world itself. Wilson is certainly not the first person to find himself tied up in this dichotomy, looking for a more basic “self” responsible for the brain’s unconscious activity.

Still, it’s not obvious how we’re to solve the problem. One popular solution is a simple change of register, from talk of conscious cognitive activity on the football pitch to talk of bodily instincts. This would solve the Rooney problem by eliminating “self” from the conversation entirely. Such an approach, however, is less a collapse of the distinction than a shift of attention from one side of it to the other.

This is nowhere more obvious than in popular treatments of the psychology of choking. In Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice, Matthew Syed takes on the “previously incomprehensible” phenomenon. Until recently, contends Syed, psychologists couldn’t explain choking — that is, how elite athletes seem to forget how to perform basic actions that are fundamental to their sport. But advances in neuroscience have given us an insight into the underlying causes of the issue.

Syed writes: “In effect, experts and novices use two completely different brain systems. Long practice enables experienced performers to encode a skill in implicit memory, and they perform almost without thinking about it. This is called expert-induced amnesia. Novices, on the other hand, wield the explicit system, consciously monitoring what they are doing as they build the neural framework supporting the task. But now suppose an expert were to suddenly find himself using the ‘wrong’ system. It wouldn’t matter how good he was because he would now be at the mercy of the explicit system.”

This is intuitive enough. Players practice specific actions precisely so they don’t have to think about doing them when they’re on the pitch. It is, by that point, second nature, muscle memory. When an expert thinks about what they’re doing, they find themselves, to use Syed’s terminology, in the “wrong system.” Compelling as this might sound, it’s no less dualist than the alternative. Only now, instead of asking how the body can be a volitional actor, we’re asking whether thinking has any place in activity at all.

Gould has voiced his frustration with this more scientific presentation of the mind-body problem. “I do think that … we seriously undervalue the mental side of athletic achievement when we equate the intellectual aspect of sports with unverbalizable bodily intuition and regard anything overtly conscious as ‘in the way,’” Gould says. “Yes, one form of unwanted, conscious mentality may be intruding upon a different and required style of unconscious cognition. But we encounter mentality in either case, not body against mind.”

Our failure, then, is not the direction from which we approach the problem, but the statement of the problem itself. To even talk about what goes on in a player’s head when they play is to commit us to a dualist picture according to which the mind and body are set apart. To solve the problem, we need to collapse this distinction: It is not that we think with our minds and do with our bodies; rather, we think with our bodies and do with our thoughts, all at the same time.

As Gould says, “Batters just don’t have enough time to judge a pitch from its initial motion and then to decide whether and how to swing. Batters must ‘guess,’ from the depths of their study and experience, before a pitcher launches his offering … such mental operations cannot proceed consciously and sequentially. But these skills do not therefore become a lesser form of intellect confined to the bodily achievements of athletes.”

~

Newton’s work expanded the gap between person and world until it became unbridgeable. Since then, however, the findings of contemporary neuroscience have shown the gap is far narrower than early modern thinking allowed. It remains to be seen, however, whether there’s a way to speak about our relationship to the world that causes this dualism to disappear entirely.

This was the problem that exercised the mind of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a French philosopher who had become obsessed with the findings of modern psychology in the mid-20th Century. What fascinated him most was the idea the body was fundamental to the process of knowledge.

For Merleau-Ponty, it was becoming increasingly obvious that, to know the world, it was essential to have a body so as to orientate yourself within that world, to expose yourself to it in such a way that it revealed itself to you. The body, then, is the crux of his philosophical system: It is a part of the material world, but also able to differentiate itself from that world, stepping back and reflecting on itself.

This is all rather abstract, but we can apply the idea to the Rooney problem. For Merleau-Ponty, when Rooney rises for an overhead kick, he’s thinking as a body, his body knows what to do. He’s not thinking in the normal sense — discursively, reflectively — but materially. And so Rooney’s explanation of his thought processes on the pitch is correct at least in this sense: He is thinking, just not in the way he describes it.

Perhaps this toggling between talk of bodily and non-bodily thinking sounds like dualism in different terms, but it differs in an important way: The point here is not to distinguish between mind and body, but between different aspects of the body’s existence. It’s not a dualism so much as a spectrum, with the body right at the center.

In this way, Merleau-Ponty reversed the process Newton had started. Where the early moderns had displaced the human knower from the world, Merleau-Ponty replaced them, this time as a body.

~

So there you have it, the story of how Isaac Newton changed the way we think about our engagement with the world and how philosophers, with the help of modern neuroscience, started to reverse the process.

But a question remains: Why does this matter? Rooney may have been wrong about what he was doing on the pitch, but he still scored the overhead kick. He could think he was being controlled by an invisible puppet master, for all we care, as long as he was scoring goals. Or take, for another example, Harry Kane’s commitment to the gambler’s fallacy: “If I miss a chance, I’m more likely to score the next.” This seems to suggest incorrect thinking isn’t only not a problem, but can even be beneficial.

We must return, then, to the beginning. At that moment, hanging between heaven and earth, waiting for the ball to meet his foot, Rooney was at the pinnacle of his career. What had led him to that point? Sure, the ability to “think” his way around the pitch. But what was that ability if not the result of a lifetime spent embodying the game, habituating himself on a field so that when that cross was delivered against Manchester City, his body already knew what to do?

To quibble over Rooney’s description of the overhead kick, then, is already to miss the point, to arrive too late to the party. That goal was not the product of a set of thoughts that ran through his mind as he waited for Nani’s cross, but of hours and hours spent on the training pitch throughout his life. You cannot, the adage goes, read a book in order to learn how to ride a bike. The same is true of football. There is no substitute for being on the pitch, for playing.

If this insight is valuable to anyone, it is surely most valuable to those of us who don’t play the game — coaches, pundits, fans. All of us seem to be stuck in the realm of the theoretical, forced to talk about the game not as an embodied experience but as a set of bodies moving around in space. From the tactics whiteboard screwed to the wall of the dressing room, to the interactive screen of Monday Night Football, we talk about football from the detached, objective perspective Newton taught us to in the 17th Century.

Of course, there’s a place for such talk. Being able to describe tactics, in particular, is important for both players and watchers of football. However, if the abstract is prioritized over the embodied, our understanding of the game will suffer. And the less we understand, the worse will be our analysis, our coaching and, ultimately, our playing.

This is not only about emphasizing the importance of the body; it’s also about finding a way to talk about conscious thought on the pitch. There are, for example, certain players we think of as particularly intelligent or cerebral. Take Andrea Pirlo, who once claimed, “I’ve understood that there is a secret: I perceive the game in a different way. It’s a question of viewpoints, of having a wide field of vision. Being able to see the bigger picture. Your classic midfielder looks downfield and sees the forwards. I’ll focus instead on the space between me and them where I can work the ball through. It’s more a question of geometry than tactics.”

This is clearly an example of what Gould termed “guessing” and, as such, “these skills do not therefore become a lesser form of intellect confined to the bodily achievements of athletes.” These skills can’t be discursive in the way Rooney describes, but neither are they simply instinctive.

We can only make this point, however, if we shed the paradigm Newton foisted upon us. So the next time you are reminded of Isaac Newton, think to yourself just how much he held back the progress of the game. The bastard has a lot to answer for.

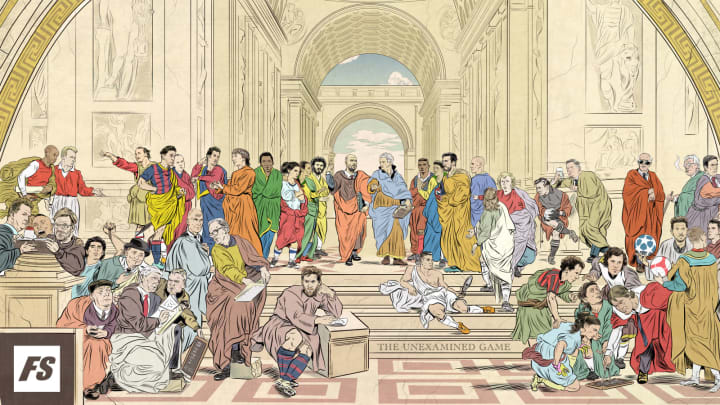

The Unexamined Game is a new series exploring the intersection of philosophy and football. You can find the previous articles in the series here:

Toward a philosophy of football