A family sketch done in naïveté is all Crayola expressions and broccoli trees. Maybe there’s a dog. Probably there’s a sun in the top right corner. The rainbow wax explosion is all families just as easily as it is no family at all. The family in the flesh will neither grow toward or away from this paper production; the real and the ideal need not even acknowledge one another’s existence. They just are, on a refrigerator door, in a packed minivan, up and down a grocery aisle, split and scattered with a dozen different zip codes between them, a change of address no one knows about, a blank where there should be next of kin.

And so it is with basketball teams. They are an idea. They are execution. The two need not meet. Sometimes they do, and, often times, a failure of imagination describes the merger as a family affair.

Aesthetic beauty on the court — sharing the ball, making the extra pass, sacrificing individual accolades — transfers well to projecting familial analogies inside a locker room. Successful teams become emblems for the greater good. They become containers for the most warm-hearted emojis. If a team fails, the family bonds simply weren’t strong enough and were never intended as something permanent. There is no legacy in an official sense. No inheritance. Only ephemeral tracings.

This metaphor is complex and carries a great number of cultural stigmas about what is and isn’t a functioning family. The language makes it easy to formulate discussions about teams with acceptable hierarchies who clearly developed the right way, which is to say via the draft and in line with their traditional antecedents. These teams don’t skip steps and are never sidetracked. The San Antonio Spurs were, at one time, the poster children for such a notion, and the Golden State Warriors have also been discussed in such a way, even while rigging the rather combustible dynamic between the corporate hitman Kevin Durant and everyone’s inappropriate uncle Draymond Green. This dynamic changes drastically if Durant and not Green is the individual drafted by the franchise. (Just ask how San Antonio, oh so long ago, dealt with David Robinson and Dennis Rodman.)

Of course, championship teams have not always been so comfortable and smug as a family road trip, even if such comfort is no more real than a child’s crayon musings. Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls and the Los Angeles Lakers with Shaq and Kobe functioned more like backrooms in The Godfather or The Wire. Then again, those worlds also lend themselves to discussing the crucible that is the modern family.

But the family way is not always tied to championship results. Almost any young team of up-and-comers becomes a band of brothers. The Denver Nuggets are currently feeling this sense of celebration and growth as if life were nothing but weddings and birthdays. Such is the bond with Damian Lillard and CJ McCollum in Portland, only times of late have grown more serious for them. Such is not the way with John Wall and Bradley Beal in Washington, even if their pettiness is an inherent part of some family’s lived experience, and yet unreasonable contracts bound them together until death do us part. Then there are the likes of Anthony Davis; he who is currently living his best loneliness on the streets of New Orleans.

More than anything, what the family metaphor does is project a team’s current personalities into a future golden age that mimes all those happy families of yesteryear. It holds tightly to loyalty and plants itself in the idea that growth can only be positive. The Milwaukee Bucks, the Philadelphia 76ers, and the Boston Celtics will all rise. They are not destined to tread water with the Minnesota Timberwolves. The Bucks have already started shedding those members of the family who are not immediate. Sometimes a franchise manicures growth. Sometimes, however, the hedge trimmer is a lightning bolt and the family tree is nothing but a charred replica of what once was. Witnesses swear the thing is dead, but come spring, new growth sprigs forth.

Take a look at Billy Donovan, now well into his fourth season as the Oklahoma City Thunder’s head coach, and you notice a graying gauntness has crept into view, tugging at his temples, leaving lines across his skin. He looks older, like some unnamed Washington Irving narrator to be found in the backroom of a backwoods nineteenth-century tavern. He is trying to coach his way out of some other bugger’s poor story. He is most likely deep in his cups, telling ghost stories and drawing up plays in the dust.

In a game against Philadelphia last Saturday, with 6.9 seconds left on the game clock, the Thunder ran a side out play. Before the team inbounded the ball, Steven Adams set a screen at the far elbow. Dennis Schröder, a refugee from Atlanta, was the first man round the screen. He finished his trajectory at the top of the key before curling toward the near corner.

Following in Schröder’s wake ran Paul George, except the inbounds pass found him at the end of his curl pattern, atop the key.

Fouled, he lay on his back with the ball passing through the hoop simultaneously to the referee’s whistle.

Jubilation ensued for those in the Thunder’s blue and orange, and George headed to the line with a chance for a four-point play. He made the foul shot. His team won the game. They would win another one the next day. Oklahoma City is now 28-18 and looking stronger and more committed to the cause than last season. Much of that is due to this season’s Paul George being both more confident and comfortable than last season’s version, but the team also just seems to be having way more fun. Ghost stories are like that.

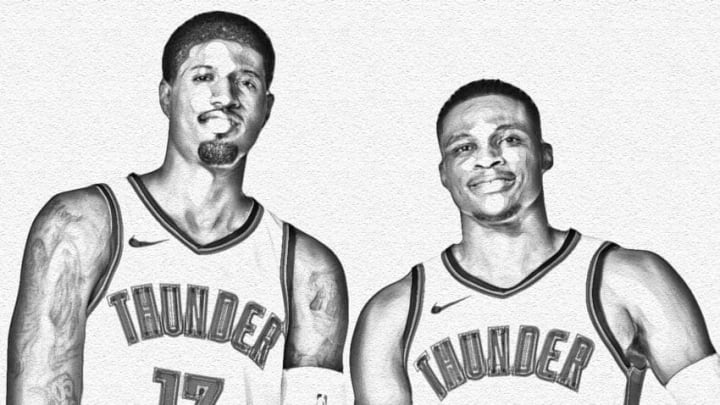

And this season is about Paul George and how he chose to stay and put up career numbers alongside Russell Westbrook on the American plains, where so much dust comes and goes and does not settle. Paul George is an MVP candidate. He is an outgrowth in a crown of mutilated branches; each one more hacked and gnawed than either pruned or clipped. The shape of this roster is the result of vacated spaces, bad trades, and failed experiments. But it works. Like this season’s results trailing last season’s, like George chasing after Schröder, like George and Schröder following in the footsteps of any former Oklahoma City player who might be better elsewhere, this roster appears to be working.

Oklahoma City is always carrying the baggage of its alternative futures with James Harden and Kevin Durant in tow. Maybe this is the curse of having moved from Seattle to Oklahoma City in the first place, of being stolen goods. Whatever, none of that is here and now and is all rather foolish and inane. Besides, Paul George is not without his own baggage.

Having once traced Icarus’ ill-fated flight across the sky, he is a hopeful tale. A player, whose career faltered after a spectacular start, found a franchise in a similar state. One could write the script as a late-career Diane Keaton rom-com, but the players involved and the franchise arcs are written with too much depth and history to simply flat line. So maybe the moments with this team do weigh more when they’re full of history and not just fluff.

This year’s Oklahoma City Thunder is a violent creation; an organism with no single origin story and a collective will not to wither. No clear path toward a higher plane of evolution has ever really existed — just a furious, whirring dervish of movement that one way or another came into being around Russell Westbrook’s personality, his reckless fashion sense and formal pettiness.

More electron cloud than spirit, Russell Westbrook’s assaults call to mind an oil-splattered James Dean or Tom Joad without a preacher. His virtuoso numerical output of the last few seasons has simultaneously demanded he be both more and less than his talents make him. No one else could have done what he did. Anyone else would have won more. The Westbrook everyone witnessed existed within the parameters of these extreme notions, and as polarizing as opinions can be about Westbrook, Westbrook’s moonlighting as a savage getaway driver kept George in Oklahoma just as easily as it drove Durant to California. He should be both praised and critiqued; there is plenty of Russell Westbrook to decipher. After all, in the words of Joel Embiid, the man is always in his feelings.

So far the 2018-19 season is a down year for Westbrook stock, which means the Thunder are on the up and up. This was always the physics in play. He would absorb everything. He would be a proverbial black hole until all that mattered sat chaotically within his grasp. Then, maybe after the math ran all the way one way and the eye test ran all the way in the other direction, the Thunder’s universe might sprawl again. In short, everyone at least knew or cheered for Westbrook to get Westbrook out of his system. Although shooting below his career percentages, but he’s still averaging a triple-double. More importantly, though, his usage rates are more in line with the days when the Thunder stood a chance against the NBA’s best teams.

The big rebound in that weekend game against Philadelphia, where Paul George hit the big three, occurred with 47.9 seconds left in the fourth quarter. Steven Adams hauled in the miss, doing his best Groot impression, and tossed it back to the perimeter. Jerami Grant then skipped the ball to Westbrook. Westbrook drove, collapsing the defense, and then dished to Terrance Ferguson who hit a big three that wasn’t quite the biggest of threes.

The Thunder now has something of a Big Three, if not as large and looming as the initial trunk and shape of years long gone or even as star-powered as last season’s failed Carmelo Anthony experiment.

Not so long ago everything for Oklahoma City began and ended with Russell Westbrook. Now the shape of what they are becoming can be traced to and from a variety of sources. In his battle with Embiid, Adams unleashed grotesque hook shots, drop steps, and one soaring dunk or two. He is something of a Groot on the low block, ferociously strong and always willing to grow. Every year he is something more than he was the previous season. Against Philadelphia, he scored the Oklahoma City’s first basket while Paul George scored the team’s last points. The Alpha and Omega now has synonyms.

After all, in between those bookends, Russell Westbrook fouled out. Without him on the floor, Dennis Schröder became Oklahoma City’s primary ball handler. While avoiding a double team in the backcourt, Schröder lofted a lazy pass to an unsuspecting Steven Adams. Philadelphia’s Jimmy Butler stole the pass and the lead with 6.9 seconds left. This kind of game humbled Oklahoma City time and time again last year. But the Thunder is, for the first time in a while, not just Westbrook’s force of will.

When Paul George hit the game winner, Westbrook stood on the sideline with a grin from ear to ear, perhaps knowing what it’s like to toss the baby out with the bathwater and still end up surrounded by family.