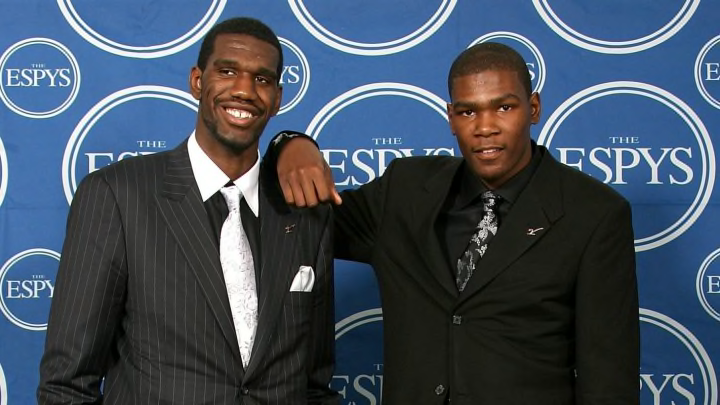

It’s one of the biggest hypotheticals in NBA Draft history — What if Kevin Durant and Greg Oden had been selected in a different order?

The 15th anniversary of the 2007 NBA Draft is here. Sorry, Blazers fans.

Let’s get this over with and delve into the latest “What If,” courtesy of Strat-O-Matic, the Market Leader in Sports Simulation.

What if the Portland Trail Blazers had drafted Kevin Durant with the No. 1 pick in the 2007 NBA Draft instead of Greg Oden?

Many people over the past few weeks, I’m sure, have examined the ins and outs of that draft class, propping up analytics and game breakdowns and old scouting reports. I’m going to eschew those options for two reasons.

First, Blazers fans have gone through enough. They’ve had to suffer with Bill Walton’s injuries; Brandon Roy’s abbreviated career; Sam Bowie over Jordan. They have gone 45 years without an NBA championship; 30 years without a Finals appearance. Enough is enough.

Second, this column is about Greg Oden, the person.

Remember that clip a while ago of a fan taunting Russell Westbrook and then immediately playing dumb when Westbrook confronted him? Athletes aren’t zoo animals. A short piece of their lives will be spent playing a sport, but that’s all we care to celebrate about them.

Greg Oden exposes the fallacy of that viewpoint. Imagine being branded as the guy who fell short before your adulthood even took off. That’s all you’re known for. That’s your identifier. Nobody cares about your opinion on global warming or Roe v. Wade or Lorde’s new hair color. All they know is that you failed; and it wasn’t like Oden squandered his talent. He was injured. A lot. It’s hard to prove your worth in street clothes.

When I talked to Oden in 2019, he was happy. He was devoted to being a dad and eager to coach. He was open to what lay ahead, a lovely development. Here’s a lengthy excerpt from that unpublished interview. (Note: I emailed Oden for an update, but I didn’t get a response.)

When did the injuries start to bother you? When did you start thinking to yourself, “Oh man, things aren’t going the way I want them to go”?

When I got cut from Portland. In my head, I know I literally went through three surgeries on my left knee at that time, just back-to-back-to-back. It was very nerve-wracking to my spirit, just realizing, “Out a year, big cat.” OK, rehab from that a year, now the microfracture, then another microfracture, that really took a hit to my spirit.

Growing up, basketball was such a pivotal part of my life and just part of my identity. Having that taken away, I literally had no direction. After three years of doing it back-to-back-to-back, it was like, “Dude, all you do is rehab. Who are you right now? Are you this basketball player just getting paid to be this basketball player?” With basketball taken away, I had to figure out what I even liked outside of the game and that was tough. In that position was so much pressure, if it wasn’t from just the basketball world, it was the pressure I put on myself. It’s just society. In a basketball-loving town of Portland, and coming from Indiana, it was just a lot going through my mind and really not knowing how to handle it. It was a lot of pressure put on myself.

Is that when the drinking started?

I think just through the injuries, not having a lot to do, trying to bide the time, trying to numb my mind, trying to numb my body, I think that’s when the drinking really picked up and got really heavy. It was a thought of, “You’re not playing anyways, it’s not going to hurt you.”

Was there anyone in your life at that point who you could turn to?

I had friends, I had my cousin [Christopher Cothran] who ended up passing away quickly from cancer. He was my favorite cousin. So that added to the pain and that added to the drinking, because it was like, even if somebody was there to [say], “Hey Greg, you might want to slow down and you might want to put your mind a little bit toward the game and your comeback,” you lose a family member, somebody who’s always been there your whole entire life. I really had no direction at that time.

How did you find that direction?

A lot of it came after Miami [in 2014]. I had that domestic violence situation and legally having to get sober and having to take AA classes. I was on probation for three years. Legally, it put me on a path where I actually had to look at myself and actually figure out the person I wanted to be. And then my daughter being born, I think that was the main thing: I realized that I couldn’t go down the same path and that things needed to change.

Do you know who you want to be now?

I want to be a great father. I want to be a positive human being. I want to help people be better and have some happiness in their life.

When people mention Greg Oden, they kind of think of you as the number-one draft pick, they think of the potential that wasn’t fulfilled. What you just said, is that how you want to be thought of, or is there another way you want the general public to know you?

Honestly, when someone says “Greg Oden” I want them to get a smirk or a smile on their face and think about a good time or a good story with me. I struggled recently trying to decide “Is that enough, is that a great way to be in this world?” But with so much negative going on in the world, why not be a person who just wants to bring positivity, who wants somebody to be happy, put a smile on their face? I think that’s something.

Oden’s stature is a victim of timing. In sports, failure works as a subplot, not as the main plot. We adore Michael Jordan getting cut from his high school team. It’s the perseverance part of the myth. (The Wizards years are an easy-to-ignore misstep, like The Godfather Part III.) But once sports end, an athlete has to go on with their life. The thing is, it can be exciting and worthwhile. A few months ago, I interviewed Tracy McGrady about his one-on-one basketball league, the OBL. He was stoked. This was a new challenge, a chance to do something that was his and his alone.

Everyone’s dreams evolve. If they didn’t, I’d be on my 30th straight year of trying to make the Mets roster. If Greg Oden had become the sequel to Bill Russell, he’d still have to face that dilemma. He has had time to figure out what’s next instead of going from hero to mortal with less time.

Even then, hitting the hard turf of reality in your 20s is terrible.

About a year after graduating college with awards and clips and great experience, I flamed out at my first newspaper job. It took me two years to return to writing and many years more to recover emotionally. And I didn’t have the media covering my lousy prospects or hounding my friends and family for details. Sources say Croatto sent two resumes last week but watched nearly five hours of Blind Date. “His mom and dad are concerned,” a longtime friend said. “Teaching or law school might be discussed soon.”

The transition from deity to mortal can happen without a prelude. That’s why I love Greg Oden for moving on. I’m rooting for him. I hope you are, too.