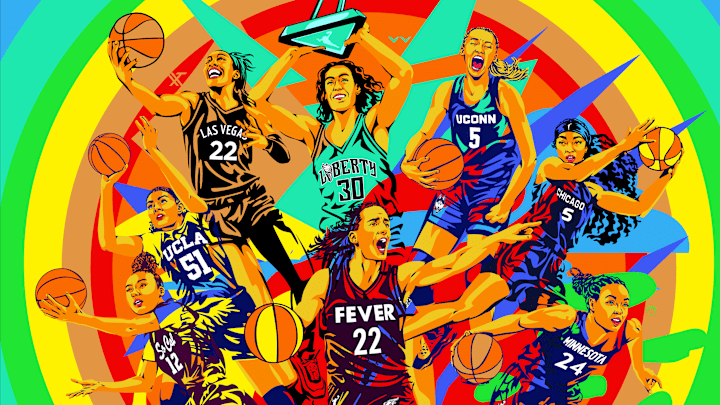

From March Madness to the Olympics and a historic WNBA season, women's basketball hit dramatic new heights in 2024 — for viewership, fan interest and on-court excitement. That's why Women's Basketball was chosen as FanSided's 2024 Sports Fandom of the Year. Check out all our 2024 Fandoms of the Year here.

Imagine if some of the most talented, massive and influential musicians in the world were prevented from taking the next step in their careers.

Imagine if the Beatles were just not allowed to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show, the television event that launched their eventual global superstardom known as Beatlemania. What about if Taylor Swift was only able to perform her Eras Tour in smaller theaters around the world rather than in larger arenas and stadiums? How about if before even putting out her own music, Beyoncé was called a flop and wasn’t paid attention to following her move from girl group Destiny’s Child to her own act as a solo artist?

That’s all difficult to imagine. It’s inconceivable. Due to the opportunities for visibility and the innate belief in their music from decision makers, the Beatles, Swift and Beyoncé all cultivated multitudinous fan bases and eventually passionate fandoms.

Women's basketball, however, a sport that is an entertainment property in its own right, has had to deal with all of those limitations throughout its history. The game suffered as a result of a lack of meaningful exposure and investment which has led to indifference and denigration.

“Apathy is the death of a brand,'' WNBA Commissioner Cathy Engelbert told USA Today earlier this year.

But in 2024, however, there is much less apathy and an undeniable hunger for women’s basketball. This past calendar year represents a turning point for the sport and its ever-evolving fanbase. For the first time ever, this past March, the Women’s NCAA National Championship game aggregated a larger audience than the Men’s NCAA National Championship game. The WNBA set single-game attendance records and record sales in merchandise during its regular season in 2024. Game 5 of the 2024 WNBA Finals was the most-watched Finals game in 25 years.

And for the first time since 2008, the WNBA held an expansion draft to launch a new team, the Golden State Valkyries. The WNBA will have more than 12 teams for the first time in 16 years and will add two more during its 2026 season.

This month the WNBA was named the fastest growing brand among all U.S. adults in 2024 by American business intelligence company Morning Consult. The W beat out brands like Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream, Brisk Iced Tea and Disney+ for the top spot.

To get to the current moment, the game that now many want a piece of has been through its share of ebbs and flows. And to understand women's basketball’s current moment, we have to understand completely what it had been up against. Why couldn’t the game just thrive? It was difficult when the cards were stacked against it.

For years, games at the college and professional level had been difficult to find on television. The WNBA lost five teams and had three more relocate in 10 of its 28 years as a league. The NCAA famously undervalued the sport until 2022. The women’s tournament wasn’t allowed to be branded as March Madness, the moniker for the NCAA tournament that draws excitement and massive fanfare.

The sport has often been criticized for even existing. Between detractors, modern and historic, critiquing the WNBA for its lack of above-the-rim play, and narratives about how the league was struggling financially, the game has been vulnerable.

The UConn Huskies women’s basketball team, one of the longest-running standard bearers within the sport, was heavily criticized in 2018 for winning too much and dominating its opponents in a way that was “a loss” for the sport. When was a men’s basketball team on the college or pro side denounced for being too dominant or striving to create a legacy and a dynasty?

For years, these hurdles have curtailed the growth potential the sport always had. Women’s basketball was stuck in a vicious cycle.

Investment in the product halted when the return on that investment didn’t come quickly enough. Women’s basketball often has been compared to the men’s game when it comes to its revenue and earnings. But these comparisons aren’t fair when the men’s side of the game on both the collegiate and pro sides had decades and decades worth of head starts.

The first men’s NCAA tournament was played in 1939 while the first women’s was held 43 years later in 1982. The NBA had its inaugural season in 1949 and the WNBA didn’t have theirs until 1997, 48 years later.

When men’s teams lost money, they continued on. But when a women’s team lost money, it was banished to a remote location and put up for sale without a buyer. A lack of investment in the product from ownership groups and collegiate governing bodies occurred alongside resistance to showcase the product on networks with larger platforms and at opportune times.

Broadcast television network CBS had the rights to the NCAA women’s title game during Cheryl Miller’s USC career in the 1980s and then all the way through UConn’s first National Championship victory in 1995. These national championship games often drew over 7 million viewers and peaked at over 11 million during Miller’s collegiate career. But in 1996, CBS let go of its rights to the title game and ESPN took over. As a result, the title game was “buried” on the cable network until 2023 when Caitlin Clark made it to her first NCAA title game and then the game was finally televised on ABC after 28 years on cable.

Flash forward to this past summer at the Olympic games in Paris when the women’s gold medal game, featuring the USA and France, drew 7.8 million viewers on NBC, a network that had begun broadcasting women’s college basketball in 2022 and will be a WNBA media partner beginning in 2026 for the first time since 2002. The game was on at 9:30 a.m. ET on a Sunday morning, while the men’s gold medal game aired at 3:30 p.m. ET on Saturday afternoon. What could have been if the women’s game had a similar slot to the men’s game, which raked in 19.5 million viewers?

Opportunities for visibility of the sport and its athletes dramatically changed in the few years leading up to 2024. And philosophies about investing in the WNBA and women’s basketball writ large as a driver of good business instead of just a charity began to change in the lead-up to this past year. 2024 will be remembered as a breakthrough year for the sport.

But what made this year the year of the dramatic breakthrough after so many trials and tribulations?

Former Iowa phenom Clark and former LSU superstar Angel Reese are often credited as the sole reasons for these changes in the status quo. Both of their followings immediately translated over to their professional teams, the Indiana Fever and Chicago Sky, in ways the WNBA hadn’t seen before. Why didn’t the same happen for three-time MVP A’ja Wilson when she became a rookie in 2018? What about her Las Vegas Aces teammate Kelsey Plum, another No.1 overall pick who previously held the NCAA women’s all-time scoring record before Clark broke it?

Clark, Reese and other 2024 rookies like Cameron Brink and Kamilla Cardoso are the result of their circumstances. It wasn’t until the 2021-22 NCAA college basketball season that athletes could make money off Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL). NIL has transformed the business of women’s basketball and has dismantled gatekeepers who prevented these athletes from gaining exposure, and in turn, investment to change their ways.

Part of what made NIL such a success for women’s basketball players was that many of the players, including Clark, Reese, UConn redshirt senior Paige Bueckers and USC sophomore JuJu Watkins, grew up not only with social media, but they grew up with examples of what self-marketing on the internet looks like.

Bueckers and Watkins in particular gained a lot of notoriety before they even stepped on campus due to their viral high school mixtapes which have hundreds of thousands of views. Organizations like Courtside Films, Overtime and WSLAM all have dedicated coverage of high school prospects on the women’s side. These coverage methods, based on mostly video, helped expose rising stars to fans across the country on a phone or a computer before they even played a game in college.

But what about when the games began? It’s worth comparing how media rights changed by the time these younger athletes were playing the college game. When three of the best WNBA players in Wilson, Breanna Stewart and Napheesa Collier were playing at South Carolina and UConn, they played at most 11 games on national cable TV partners. Most national games were on ESPN2 with ESPN, FS1 and CBSSN taking a few games here and there. In 2016 when Stewart and Collier helped the Huskies win their fourth National Title in a row during the 2015-16 season, none of the games were broadcast on the big four commercial networks (CBS, FOX, NBC and ABC). When Wilson played in her final season before turning pro a couple of years later, not much had changed.

Flashing forward to the 2024-25 college season, and the networks involved have grown and changed. The defending champions South Carolina Gamecocks are playing 14 of their 32 regular season games on national TV partners. This season the Gamecocks have been on TNT, big four network FOX and will have a game aired on other big four network ABC in February when the Huskies come to town. As for UConn, the Huskies are playing 11 of their 31 regular season games on national TV partners. Five of those 11 games will air on big four networks FOX and ABC.

To put pressure on television partners and decision-makers over the years, the greater women’s sports community embraced the phrase “If you build it, they will come,” a line adapted from the 1989 film Field of Dreams. It’s a phrase that counters the common misconception that “nobody watches women’s sports,” which we now know is not the case. It’s a philosophy that helped make the case for showing games not only on more networks but on networks with a larger reach.

But as a result of increased exposure on the college side and also on the WNBA side, there also have been growing pains. The sport has dealt with uninformed television personalities creating narratives that aren’t always based in fact. An example of this was the idea that the entire WNBA was either against Clark or jealous of her because of how physically her opponents were playing her. There was a misunderstanding from media personalities and some new fans that the WNBA was not always a physical and competitive league.

These misinformed dialogs then led to online vitriol from fans targeting individual players who guarded Clark like the Connecticut Sun’s Dijonai Carrington. Sometimes that online abuse translated into public harassment. This past June, Reese’s Chicago Sky were targeted outside of their team hotel. Sky Guard Chennedy Carter, who fouled Clark hard a few days prior, was singled out by a man on the street in Washington, D.C.

This harassment hasn’t only been about Clark and those in her orbit. Stewart’s wife Marta Xargay Casademont received a homophobic email following Game 1 of this year’s WNBA Finals when Stewart missed a free throw that then resulted in a New York Liberty loss.

While there is great attention and care for the sport, that hasn’t come without a price. And while Commissioner Engelbert fumbled to address this issue initially when asked, she later denounced the harassment during her State of the League press conference this past October.

“That type of conduct is not representative of the WNBA's character or fan base,” she said. “As a league, we stand united in condemning racism and all forms of hate. The WNBA is one of the most inclusive and diverse professional sports leagues in the world, and we will continue to champion those values. We'll meet with the Players Association, the players, teams. We'll work together to expand and enhance our efforts and are going to approach this multidimensionally, utilizing technology, prioritizing mental health, reinforcing physical security and increasing monitoring.”

It’s also worth considering that Clark, Reese and soon-to-be Bueckers and Watkins play and will play in a very different WNBA than the one that veteran stars Wilson, Stewart, Collier and Plum entered in the late 2010s.

At the beginning of the 2020s, the WNBA negotiated what was at the time a historic collective bargaining agreement (CBA) that saw advancements in child care and family planning benefits for players. But the agreement was also historic because of how it allowed for more player movement, limiting the league’s core designation (similar to the NFL’s salary tag) to two years after it had been four.

When Candace Parker left Los Angeles to return to her hometown Chicago to play for the Sky, media coverage of the league changed. After years of the league struggling to tell stories during the offseason with most of its star players overseas, the flexibility for more player movement opened up the door for the WNBA to have its own designated free agency period that excites and engages media members and fans.

When the league played its bubble season in Florida as a response to the global COVID-19 pandemic months following the newly negotiated CBA, the WNBA gained an audience that was craving entertainment and escape.

During that bubble season, the WNBA's Orange Hoodie became a major fashion trend and the greater platform gave the league an opportunity to solidify itself as not only a basketball league but as a league of people who fight for equality and justice. The WNBA’s decision to dedicate the season to the #SayHerName Campaign and then eventually endorse then-Senate candidate Raphael Warnock helped attract new legions of fans who aren’t typically sports fans first.

That approach has carried over past the pandemic and into local arenas. The 2024 WNBA Champions the New York Liberty and their Mascot Ellie the Elephant have redefined how to entertain, engage and draw fans into WNBA basketball. While some clearly come for the basketball which includes Stewart, 2024 Finals MVP Jonquel Jones, and dynamic combo guard Sabrina Ionescu, others come for the Mascot and can’t wait to see what dance move or sassy and theatrical thing Ellie does next.

These younger stars in Clark, Reese and eventually Bueckers and Watkins come into a league with an ecosystem much more developed than it was a decade ago. They are joining a league that knows its brand and its audience more than it did a decade ago. They are joining a league that has the human capital capable of marketing its most transcendent stars. When Engelbert came into the league, the WNBA had a marketing team of one which has now ballooned to over two dozen.

In 2024 and beyond, women’s basketball players now can have their Ed Sullivan Moment. They are selling out arenas instead of being forced to play in theaters — yes, WNBA games have been played at Radio City Musical Hall. They are being embraced by legions of fans instead of being told that people don’t care to watch. That is why 2024 was the year of women’s basketball.

For more great women's basketball coverage, check out our hub pages for the WNBA and Women's College Basketball, as well as The Player's Tribune podcast, Sometimes I Hoop, hosted by Haley Jones.